Mapping Segregation in Montgomery County

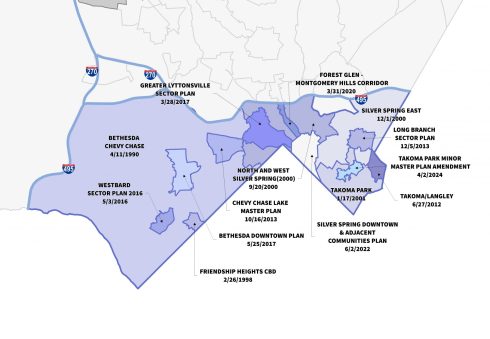

To advance the county’s commitment to racial equity, Montgomery Planning’s Historic Preservation Office, Research and Strategic Projects Division, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Team will build a mapping tool that shows historical patterns of segregation in Montgomery County. This is the first phase of a multi-phase project that would result in a collection of geo-referenced information for the purpose of creating a spatial narrative regarding the development of the county. Phase 1, initiated in FY22, is dedicated to conducting land record and plat analysis for all neighborhoods and subdivisions recorded inside the Beltway prior to 1953. Montgomery Planning will use primary source materials to determine which neighborhoods were constructed with or later adopted racial restrictive covenants. These covenants were private contractual agreements that prohibited the sale, rent, lease, or occupation of property to particular groups of people. This research will then be used to create new GIS maps and layers showing the covenants and restrictions at the subdivision level. Further analysis will track the racial and demographic profiles of these areas into the 21st Century.

View the working draft interactive map.

View the December 1, 2022 staff report to the Planning Board and Attachment A of the report.

View the February 2, 2023 staff report to the Planning Board.

How Housing Discrimination Impacted Population Growth

Various types of legal housing discrimination existed in the United States in the first three-quarters of the 20th Century, each of which contributed to the disproportionately and persistently low rates of homeownership and housing wealth among Black Americans. The legacy of this discrimination is apparent in housing and wealth inequities that persist into the 21st Century.

Montgomery Planning seeks to understand how the private and public sectors channeled racial population growth and influenced the spatial development of Montgomery County in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For the first 20 years after the Civil War, the Black population remained relatively stable and accounted for approximately 36 percent of the county’s population. Montgomery County had 7,434 and 9,685 Black residents in 1870 and 1890, respectively. The number of Black residents, however, stagnated and at times decreased while the white population grew exponentially over the next 70 years. Between 1890 and 1960, the white population increased from 17,500 to 327,736, (+ 1,773 %). In comparison, the Black population increased from 9,685 to 11,527, (+ 19 %). These racial population shifts were not the result of organic growth. Rather, they occurred due to the specific actions of land developers, property owners, real estate boards, and the government who used de jure and de facto segregation to limit opportunities for Black Americans by directing investments into majority white communities, prohibiting Black homeownership in those neighborhoods, and controlling the development of entire communities.

Project Goals

The Mapping Segregation Project will help Montgomery Planning document and explain how the real estate industry, laws, government programs, and other institutionalized and systemic actions led to the inequitable development of Montgomery County. We are part of a national movement of planners, researchers and public historians who are examining this history in our own community, but we are using novel tools and creating spatial maps to share this data.

In the initial phase of the project, Montgomery Planning will explore three different records:

- subdivision plats located in the Downcounty (inside the Beltway) area of Montgomery County; and

- mortgages refinanced by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC).

The analysis of racial restrictive covenants will focus inside the Beltway, but research into the HOLC records will be countywide.

Montgomery Planning will sample properties within each subdivision plat near its time of recordation to identify and analyze racial restrictive covenants produced by real estate developers, builders, and owners. Montgomery Planning will analyze at a minimum 2,000 plats recorded inside the Beltway, which will allow the department to document covenants and show trends.

Land records show that the HOLC refinanced hundreds of mortgages for Montgomery County residents. Montgomery Planning will review and analyze each record to determine: 1) the race of the individual who received a loan; 2) the location of each Black-owned refinanced property; 3) the total number of loans provided to Black homeowners; 4) whether the rate of access to said loans was proportionate with Black homeownership; and 5) how access to the HOLC program by Black Montgomery County residents compares to nationwide trends.

Frequently Asked Questions

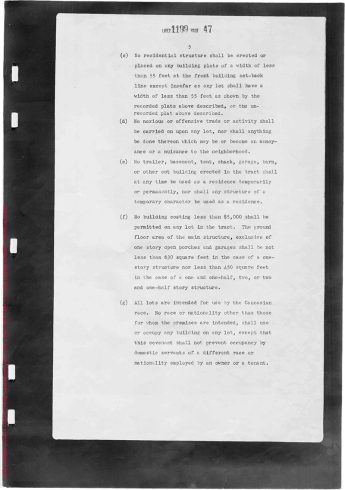

Racial restrictive covenants are private contractual agreements that prohibit the sale, rent, lease, or occupation of property to particular groups of people. These covenants are found in the land (deed) records. In the first half of the twentieth century, real estate developers, neighborhood associations, and property owners used racial restrictive covenants to create racially homogeneous white neighborhoods and prohibit homeownership and occupancy by nonwhites with the belief that this would maintain or bolster residential property values and provide long-term profitability. Racial restrictive covenants found in Montgomery County land records listed the following groups as excluded: Asian, Armenian, Black, Chinese, Greek, Indian, Japanese, Jewish, Mongolian, Persian, Syrian, Turkish, and non-caucasian. These types of covenants became especially common for a variety of reasons including the outlawing of race-based municipal zoning, rising racial and racial/ethnic tensions in fast-growing cities, and the acceptance of marketing efforts by white property owners that neighborhood stability required racial exclusivity. In 1928, the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Corrigan v. Buckley confirmed the legality of the practice which furthered its popularity throughout the nation. An entire generation of Black Americans and other racial, ethnic, and religious minorities suffered from these discriminatory practices before the United States Supreme Court deemed racial covenants to be unenforceable by the state in Shelley v. Kramer in 1948. Private citizens, however, were still permitted to include these covenants in deeds until the Fair Housing Act outlawed them altogether in 1968.

There are two types of racial restrictive covenants. In the first type, real estate developers and builders proactively incorporated covenants in subdivisions before the sale or occupation of the lots. Racial restrictive covenants were written into each individual conveyance or established over entire sections of subdivisions as part of Declarations of Covenants. In the second type, private homeowners and community associations reactively coordinated to set up racial restrictive covenants in existing neighborhoods to ensure the neighborhood’s racial homogeneity over time.

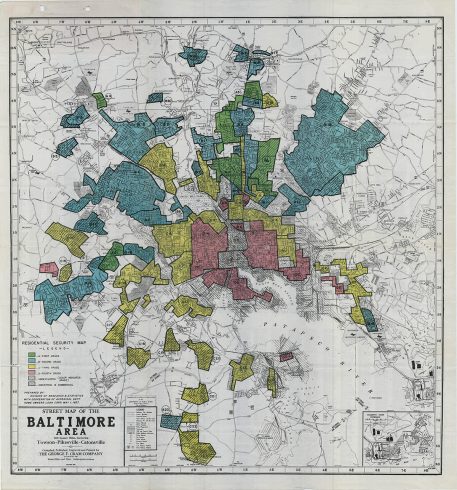

Redlining refers to discrimination that bases lending decisions on the location of a property and characteristics of the property and its owner. Typically, redlining refers to the practice of lenders refusing loans to Black communities and areas with perceived risks. The term originated from mapmakers who scored neighborhoods based on not only the physical conditions of its housing, but also the class, race, and ethnicity of the people. Concentrations of African Americans and other nonwhite residents, as well as signs of declining white majorities, contributed to lower ratings for neighborhoods. Mapmakers shaded or outlined these neighborhoods red to indicate where loans should be limited or denied. Federal government programs legitimized and reaffirmed this practice established by realtors, developers, etc. who sought to influence local and state affairs.

While historians’ initial research suggested that redlining originated with the federal government’s New Deal programs (such as the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration), new scholarship suggests that such practices predated the creation of these agencies and the government’s redlining maps, and that redlining during the New Deal reinforced existing patterns of segregation. Nevertheless, federal recognition and acceptance of longstanding racialized practices in the real estate industry perpetuated and further disseminated the myth that people of color depreciated property values.

On June 13, 1933, President Roosevelt signed the Home Owners’ Loan Act to save the besieged real estate market during the Great Depression. The law established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The HOLC’s mission consisted of two phases. During the first phase (1933-1936), the organization focused on acquiring distressed residential mortgages from lenders and refinancing them with easier terms to free capital for reinvestment. The government acquired existing mortgages as lenders turned over their holdings for government bonds as this guaranteed a return on their investment. The agency (which stopped receiving new applications in June 1935) provided one million loans and held more than 20 percent of all mortgages on nonfarm dwellings. Recent scholarship demonstrated that the agency provided loans to different racial and ethnic groups proportional to their levels of homeownership. Race, however, clearly played a role as the agency identified the racial makeup of applicant’s neighborhoods and constrained opportunities within the existing pattern of segregation. Furthermore, the recapitalization of lenders further benefited white creditors who held the majority of mortgages on Black-owned homes.

The HOLC managed, sold, and eventually liquidated its real estate holdings (which it acquired through defaults) in its second phase (1935-1951). It was during this time that the agency created its notorious redlining maps as it sought to collect data to protect the country’s mortgage industry. The Mortgagee Rehabilitation Division conducted surveys of over 200 cities that identified nonwhite and other neighborhoods considered to have poor investment potential. Although the HOLC maps reveal strikingly racist language and criteria used to classify neighborhoods, they were less instrumental in creating patterns of residential segregation than previously thought. This is because the HOLC had already made 90% of its loans prior to the creation of their maps. The division created the maps to understand the risks of the agency’s mortgage portfolio and guide the resale of defaulted properties. Thus, rather than creating housing segregation, the HOLC program appears to have further entrenched existing patterns of housing discrimination by keeping people in their already-segregated neighborhoods and by stabilizing the mostly white banking and finance industry. New scholarship contends that the HOLC limited distribution of its maps to the public and that the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) bore greater responsibility on federal-sponsored redlining that limited the ability of Black homeowners to accumulate wealth through housing. Both agencies, however, helped codify and expand practices of segregation.

The Mapping Inequality Project: Redlining in New Deal America has digitized all remaining HOLC maps. However, a map for Washington, D.C. and its surrounding municipalities has never been found.

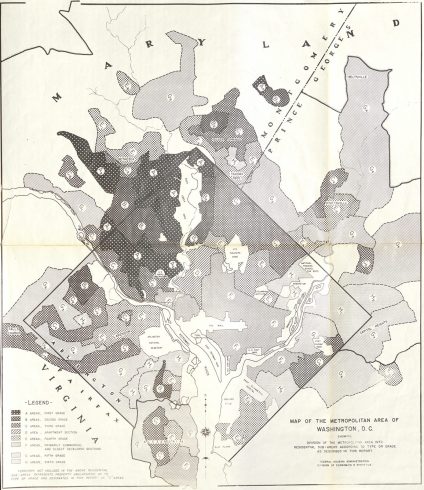

President Roosevelt signed the National Housing Act, which established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), in 1934. THE FHA had two central policy goals: 1) create an economically sound, publicly-sponsored, system of mortgage insurance; and 2) revive the depressed residential construction industry that collapsed during the Great Depression. While the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) lending program focused on refinancing, the FHA’s provided insurance for loans for new home construction.

The FHA had a profound impact on the nationwide exacerbation of residential racial segregation as it overwhelmingly insured loans for new construction in mostly white suburban communities. The FHA developed a risk-rating system that influenced private lenders and produced widely disseminated instructions for appraising neighborhood risk through its Underwriting Manual. Lenders adopted FHA’s guidelines to secure FHA insurance which protected against potential loss and principally guaranteed resale of the loan on the secondary mortgage market. The FHA perceived neighborhood change, specifically racial transitions, as a cause for diminished property values. The Underwriting Manual (1938) stated the following:

Areas surrounding a location are investigated to determine whether incompatible racial and social groups are present, for the purpose of making a prediction regarding the probability of the location being invaded by such groups. If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. A change in social or racial occupancy generally contributes to instability and a decline in values.

The Underwriting Manual also advocated for including and enforcing deed restrictions at the time of sale as an effective way of preventing a house’s—and eventually a neighborhood’s—value from declining due to a change in its racial composition. These discriminatory views were not new to the real estate industry, but had never been applied or endorsed by the federal government as no previous federal mortgage programs existed.

The FHA conducted surveys and produced their own series of evaluation maps. Between 1937 and 1942, the agency created Housing Market Analyses for select cities including the District of Columbia. The Mapping Segregation in Washington, D.C. project has geo-referenced the Residential Sub-Areas map that includes sections of Montgomery County bordering the city. The area descriptions that accompany the map explain the gradation system and utilize race as a primary component for investment security.

Several communities have undertaken efforts to document historical discriminatory practices. Of the seven profiled below, Mapping Segregation DC and Segregated Seattle are the most thorough and applicable to Montgomery County’s current efforts. Restricted covenants factor prominently in both projects, and both also include related historical information.