Montgomery Parks and Planning’s Historic Markers Program

Montgomery Planning’s Historic Preservation Office has initiated “Remarkable Montgomery: Untold Stories,” an ongoing project to install historic markers around the county that highlight underrepresented topics in local history.

Both Montgomery Planning and Montgomery Parks will be installing “Remarkable Montgomery: Untold Stories” markers throughout the county in a shared effort to bring greater recognition to people, places, and events with significant histories that we have undervalued in the past. The markers, which offer more flexibility than a formal designation on Montgomery County’s Master Plan for Historic Preservation, tell stories of people and places that shaped our communities, even where physical evidence of those histories may no longer exist.

Focused on Equity

The Historic Preservation Office is committed to enacting Montgomery Planning’s Equity Agenda for Planning. In part, this includes acknowledging that the practice of historic preservation has long overlooked histories and historic sites related to non-dominant groups. To begin to address this imbalance, the marker program will bring forward histories tied to county residents’ struggles for racial and social justice and the stories of people who broke the boundaries of their times.

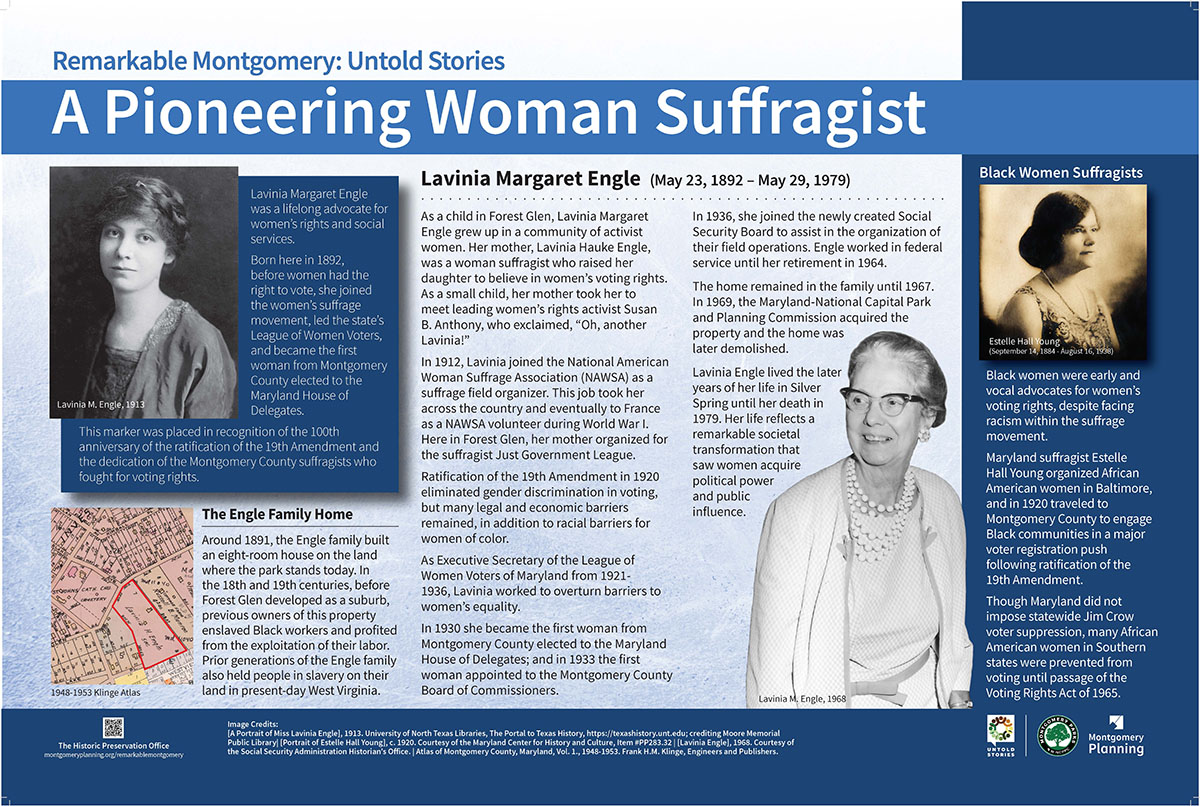

A Pioneering Woman Suffragist: Lavinia Engle

Forest Glen Neighborhood Park

Lavinia Margaret Engle was a lifelong advocate for women’s rights and social services.

Lavinia Margaret Engle was a lifelong advocate for women’s rights and social services.

Born here in 1892, before women had the right to vote, she joined the women’s suffrage movement, led the state’s League of Women Voters, and became the first woman from Montgomery County elected to the Maryland House of Delegates.

This marker was placed in recognition of the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment and the dedication of the Montgomery County suffragists who fought for voting rights. The Engle Family Home

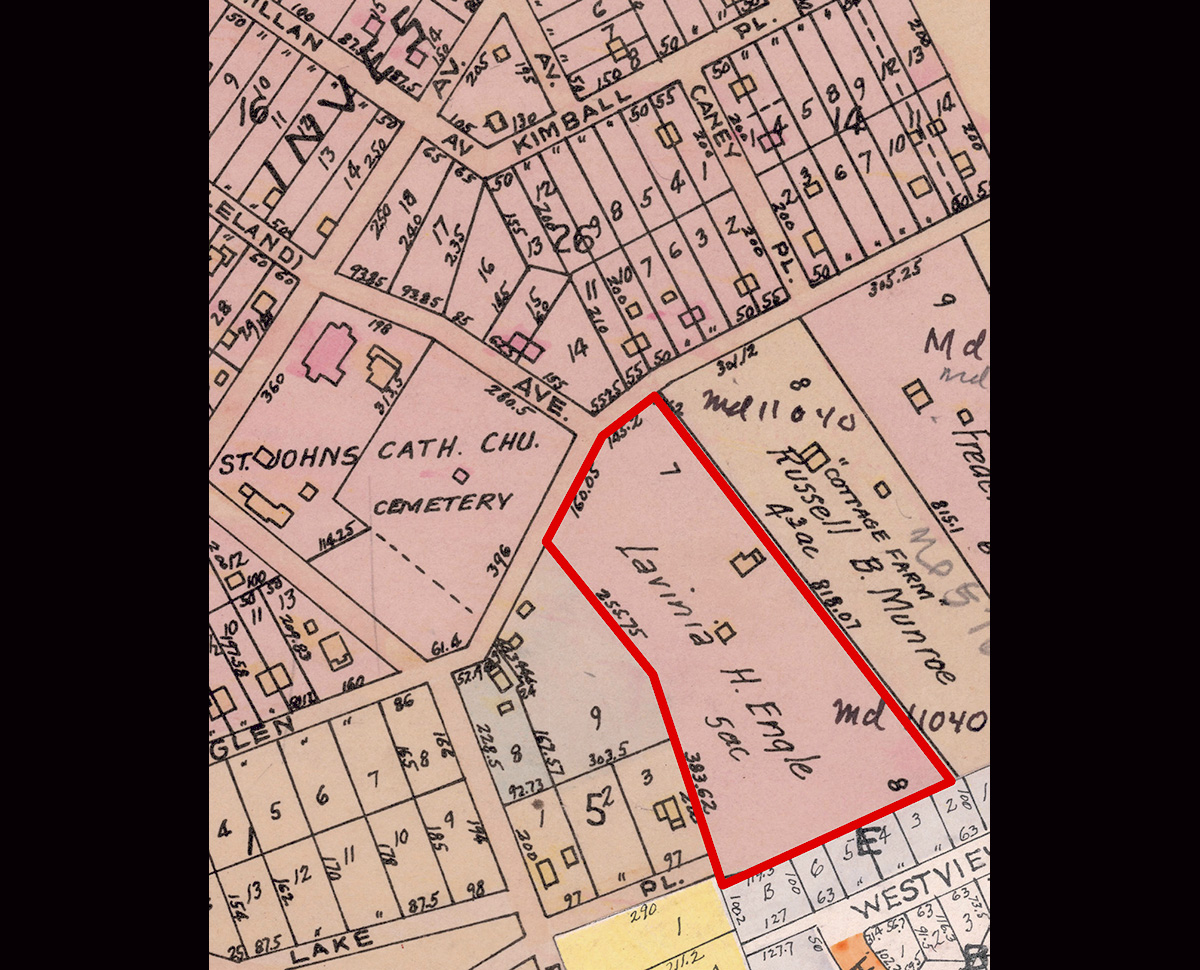

The Engle Family Home

Around 1891, the Engle family built an eight-room house on the land where the park stands today. In the 18th and 19th centuries, before Forest Glen developed as a suburb, previous owners of this property enslaved Black workers and profited from the exploitation of their labor.

Image credit: Atlas of Montgomery County, Maryland, Vol. 1., 1948-1953. Frank H.M. Klinge, Engineers and Publishers. As a child in Forest Glen, Lavinia Margaret Engle grew up in a community of activist women. Her mother, Lavinia Hauke Engle, was a woman suffragist who raised her daughter to believe in women’s voting rights.

As a child in Forest Glen, Lavinia Margaret Engle grew up in a community of activist women. Her mother, Lavinia Hauke Engle, was a woman suffragist who raised her daughter to believe in women’s voting rights.

As a small child, her mother took her to meet leading women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony, who exclaimed, “Oh, another Lavinia!”

In 1912, Lavinia joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) as a suffrage field organizer. This job took her across the country and eventually to France as a NAWSA volunteer during World War I. Here in Forest Glen, her mother organized for the suffragist Just Government League. Ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 eliminated gender discrimination in voting, but many legal and economic barriers remained, in addition to racial barriers for women of color.

As Executive Secretary of the League of Women Voters of Maryland from 1921-1936, Lavinia worked to overturn barriers to women’s equality.

In 1930 she became the first woman from Montgomery County elected to the Maryland House of Delegates; and in 1933 the first woman appointed to the Montgomery County Board of Commissioners. In 1936, she joined the newly created Social Security Board to assist in the organization of their field operations. Engle worked in federal service until her retirement in 1964.

Photo credit: [A Portrait of Miss Lavinia Engle], 1913. University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Moore Memorial Public Library The home remained in the family until 1967. In 1969, the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission acquired the property and the home was later demolished.

The home remained in the family until 1967. In 1969, the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission acquired the property and the home was later demolished.

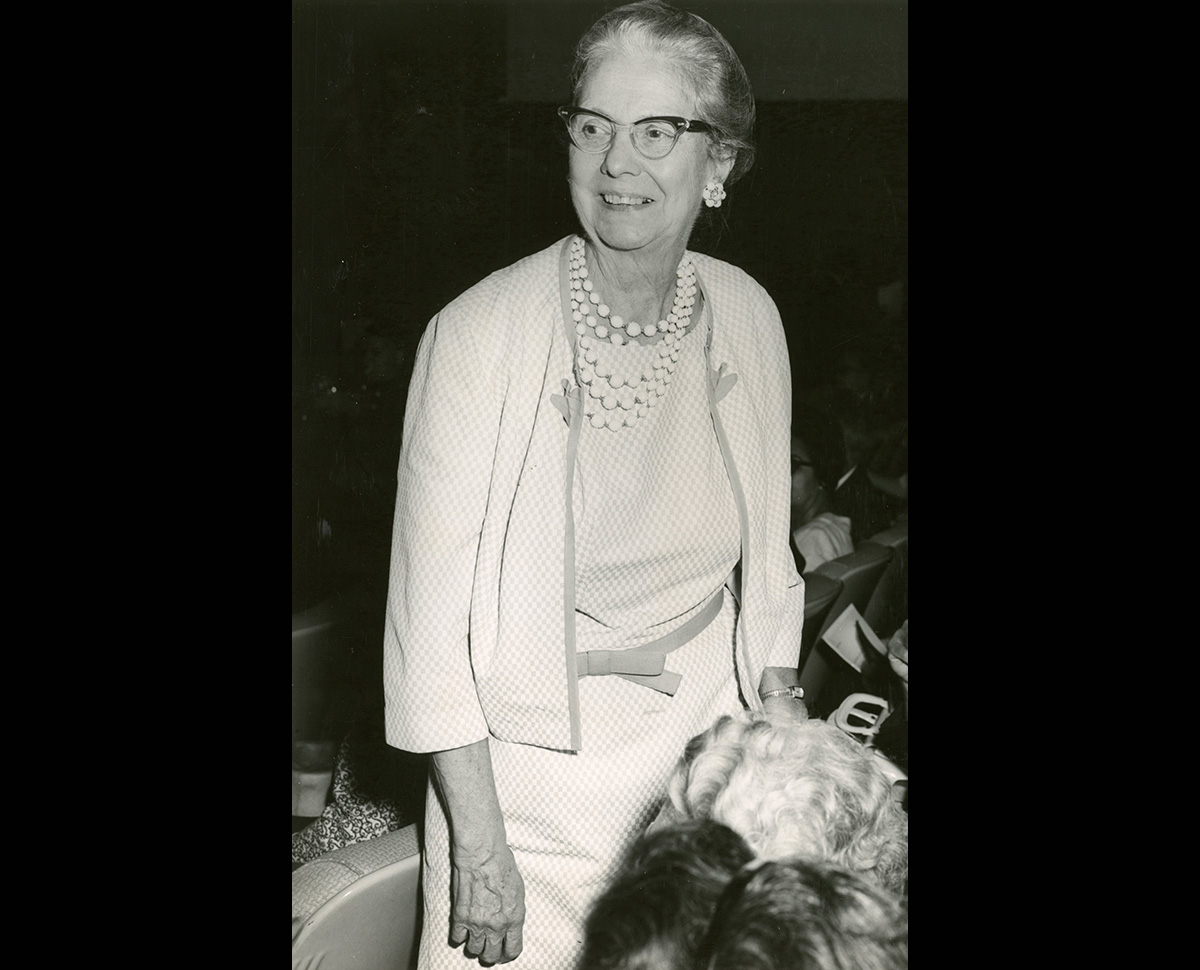

Lavinia Engle lived the later years of her life in Silver Spring until her death in 1979. Her life reflects a remarkable societal transformation that saw women acquire political power and public influence.

Photo credit: [Lavinia Engle], 1968. Courtesy of the Social Security Administration Historian’s Office. Black Women Suffragists

Black Women Suffragists

Estelle Hall Young, September 14, 1884-August 16, 1938 (pictured on right side of marker)

Black women were early and vocal advocates for women’s voting rights, despite facing racism within the suffrage movement.

Maryland suffragist Estelle Hall Young organized African American women in Baltimore, and in 1920 traveled to Montgomery County to engage Black communities in a major voter registration push following ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Though Maryland did not impose statewide Jim Crow voter suppression, many African American women in Southern states were prevented from voting until passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Photo credit: [Portrait of Estelle Hall Young], c. 1920. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, Item #PP283.32

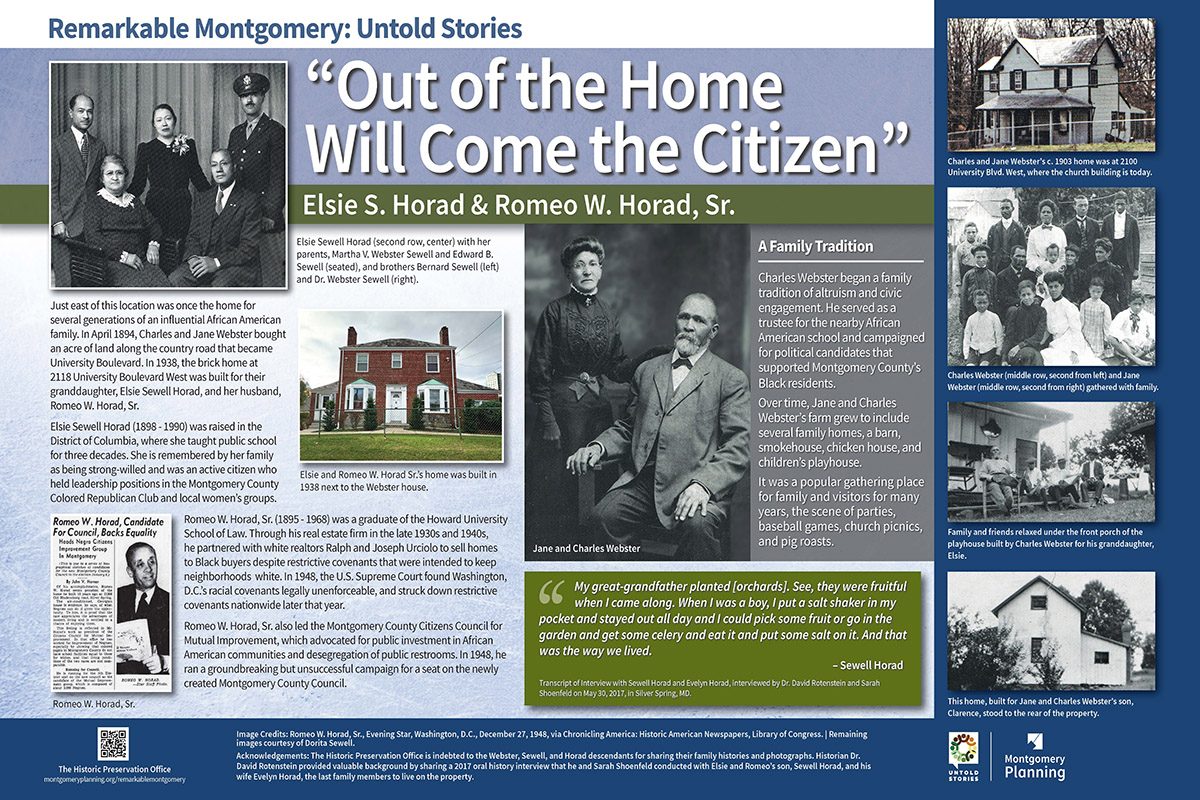

“Out of the Home Will Come the Citizen”: Elsie S. Horad & Romeo W. Horad, Sr.

Wheaton Veterans Urban Park

Just east of this location was once the home for several generations of an influential African American family. In April 1894, Charles and Jane Webster bought an acre of land along the country road that became University Boulevard.

Just east of this location was once the home for several generations of an influential African American family. In April 1894, Charles and Jane Webster bought an acre of land along the country road that became University Boulevard.

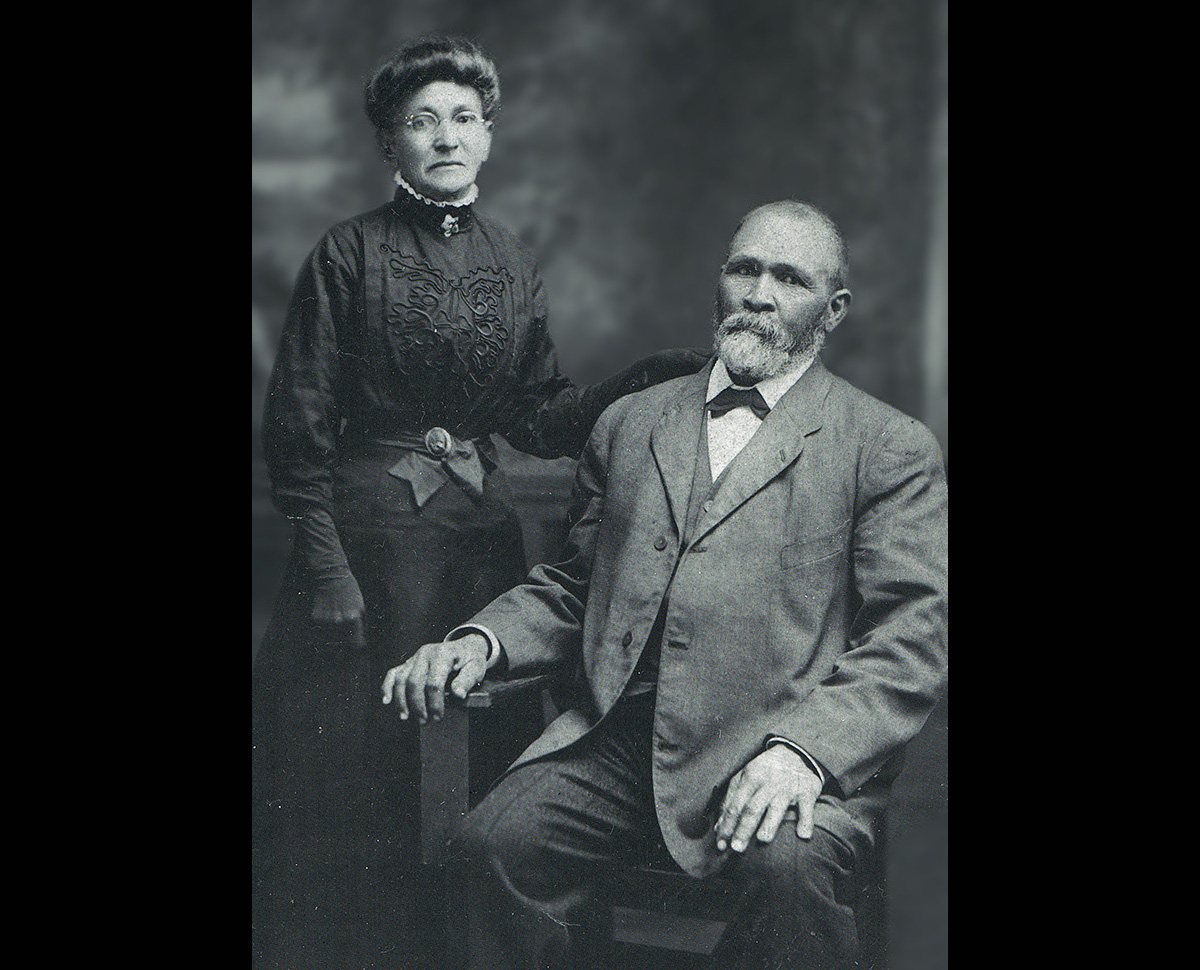

Acknowledgements: The Historic Preservation Office is indebted to the Webster, Sewell, and Horad descendants for sharing their family histories and photographs. Historian Dr. David Rotenstein provided valuable background by sharing a 2017 oral history interview that he and Sarah Shoenfeld conducted with Elsie and Romeo’s son, Sewell Horad, and his wife Evelyn Horad, the last family members to live on the property. Elsie Sewell Horad (second row, center) with her parents, Martha V. Webster Sewell and Edward B. Sewell (seated), and brothers Bernard Sewell (left) and Dr. Webster Sewell (right)

Elsie Sewell Horad (second row, center) with her parents, Martha V. Webster Sewell and Edward B. Sewell (seated), and brothers Bernard Sewell (left) and Dr. Webster Sewell (right)

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell. In 1938, the brick home at 2118 University Boulevard West was built for their granddaughter, Elsie Sewell Horad, and her husband, Romeo W. Horad, Sr.

In 1938, the brick home at 2118 University Boulevard West was built for their granddaughter, Elsie Sewell Horad, and her husband, Romeo W. Horad, Sr.

Elsie Sewell Horad (1898 - 1990) was raised in the District of Columbia, where she taught public school for three decades. She is remembered by her family as being strong-willed and was an active citizen who held leadership positions in the Montgomery County Colored Republican Club and local women’s groups.

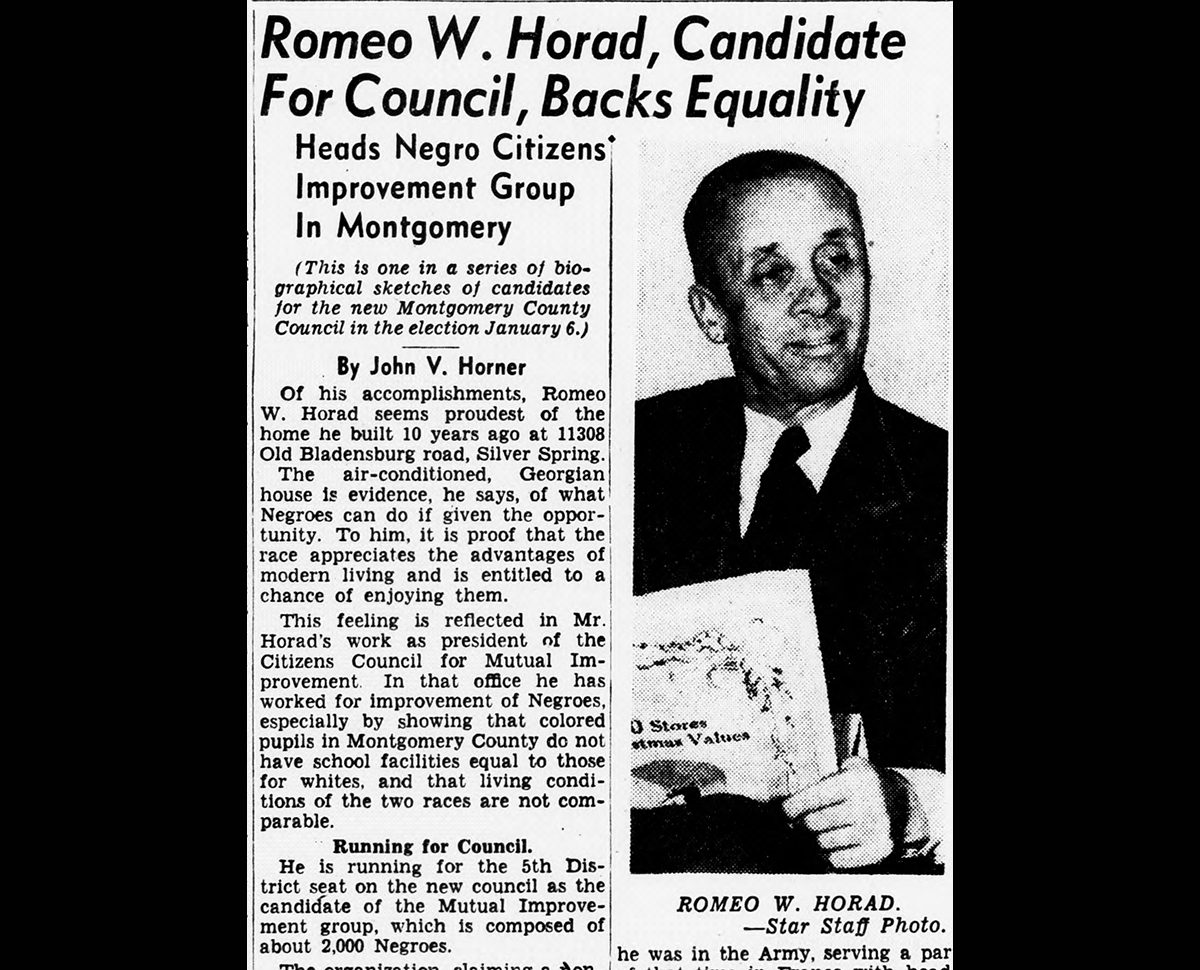

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell. Romeo W. Horad, Sr. (1895 - 1968) was a graduate of the Howard University School of Law. Through his real estate firm in the late 1930s and 1940s, he partnered with white realtors Ralph and Joseph Urciolo to sell homes to Black buyers despite restrictive covenants that were intended to keep neighborhoods white. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court found Washington, D.C.’s racial covenants legally unenforceable, and struck down restrictive covenants nationwide later that year.

Romeo W. Horad, Sr. (1895 - 1968) was a graduate of the Howard University School of Law. Through his real estate firm in the late 1930s and 1940s, he partnered with white realtors Ralph and Joseph Urciolo to sell homes to Black buyers despite restrictive covenants that were intended to keep neighborhoods white. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court found Washington, D.C.’s racial covenants legally unenforceable, and struck down restrictive covenants nationwide later that year.

Romeo W. Horad, Sr. also led the Montgomery County Citizens Council for Mutual Improvement, which advocated for public investment in African American communities and desegregation of public restrooms. In 1948, he ran a groundbreaking but unsuccessful campaign for a seat on the newly created Montgomery County Council.

Image credit: Evening Star, December 27, 1948, via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress A Family Tradition

A Family Tradition

Charles Webster began a family tradition of altruism and civic engagement. He served as a trustee for the nearby African American school and campaigned for political candidates that supported Montgomery County’s Black residents.

Over time, Jane and Charles Webster’s farm grew to include several family homes, a barn, smokehouse, chicken house, and children’s playhouse.

It was a popular gathering place for family and visitors for many years, the scene of parties, baseball games, church picnics, and pig roasts.

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell. Charles and Jane Webster’s c. 1903 home was at 2100 University Blvd. West, where the church building is today.

Charles and Jane Webster’s c. 1903 home was at 2100 University Blvd. West, where the church building is today.

"My great-grandfather planted [orchards]. See, they were fruitful when I came along. When I was a boy, I put a salt shaker in my pocket and stayed out all day and I could pick some fruit or go in the garden and get some celery and eat it and put some salt on it. And that was the way we lived." – Sewell Horad

Transcript of Interview with Sewell Horad and Evelyn Horad. interviewed by Dr. David Rotenstein and Sarah Shoenfeld on May 30, 2017, in Silver Spring, MD.

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell.

Charles Webster (middle row, second from left) and Jane Webster (middle row, second from right) gathered with family.

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell. Family and friends relaxed under the front porch of the playhouse built by Charles Webster for his granddaughter, Elsie.

Family and friends relaxed under the front porch of the playhouse built by Charles Webster for his granddaughter, Elsie.

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell. This home, built for Jane and Charles Webster’s son, Clarence, stood to the rear of the property.

This home, built for Jane and Charles Webster’s son, Clarence, stood to the rear of the property.

Photo courtesy of Dorita Sewell.

The Commonwealth Farm: “Everything We Put Our Hand to Prospered”

Peachwood Neighborhood Park

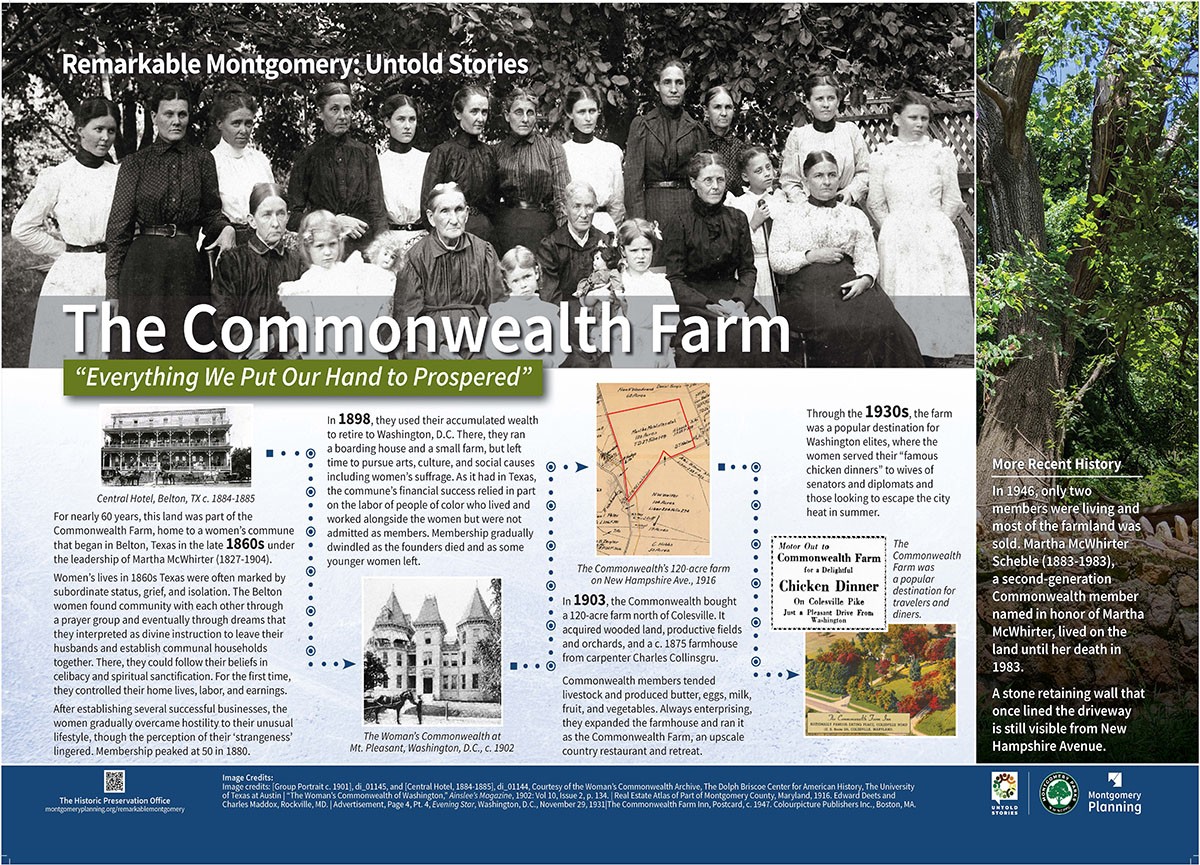

For nearly 60 years, this land was part of the Commonwealth Farm, home to a women’s commune that began in Belton, Texas in the late 1860s under the leadership of Martha McWhirter (1827-1904).

For nearly 60 years, this land was part of the Commonwealth Farm, home to a women’s commune that began in Belton, Texas in the late 1860s under the leadership of Martha McWhirter (1827-1904). Central Hotel, Belton, TX c. 1884-1885

Central Hotel, Belton, TX c. 1884-1885

Women’s lives in 1860s Texas were often marked by subordinate status, grief, and isolation. The Belton women found community with each other through a prayer group and eventually through dreams that they interpreted as divine instruction to leave their husbands and establish communal households together. There, they could follow their beliefs in celibacy and spiritual sanctification. For the first time, they controlled their home lives, labor, and earnings. After establishing several successful businesses, the women gradually overcame hostility to their unusual lifestyle, though the perception of their ‘strangeness’ lingered. Membership peaked at 50 in 1880.

Photo credit: [Central Hotel, 1884-1885], di_01144, Courtesy of the Woman’s Commonwealth Archive, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin | Group protrait of Commonwealth Farm Women c. 1901 (left), The Woman’s Commonwealth at Mt. Pleasant, Washington, D.C., c. 1902 (right)

Group protrait of Commonwealth Farm Women c. 1901 (left), The Woman’s Commonwealth at Mt. Pleasant, Washington, D.C., c. 1902 (right)

In 1898, they used their accumulated wealth to retire to Washington, D.C. There, they ran a boarding house and a small farm, but left time to pursue arts, culture, and social causes including women’s suffrage. As it had in Texas, the commune’s financial success relied in part on the labor of people of color who lived and worked alongside the women but were not admitted as members. Membership gradually dwindled as the founders died and as some younger women left.

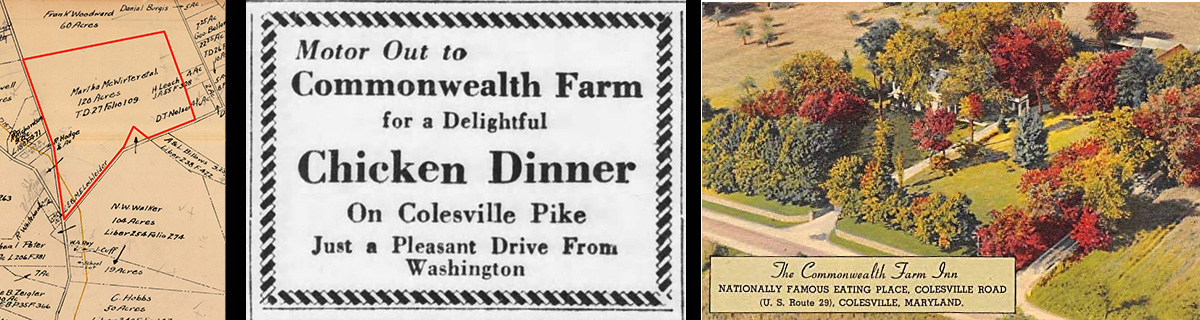

Photo credits: (left) [Group Portrait c. 1901], di_01145, Courtesy of the Woman’s Commonwealth Archive, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin; (right) “The Woman’s Commonwealth of Washington,” Ainslee’s Magazine, 1902: Vol 10, Issue 2, p. 134. The Commonwealth’s 120-acre farm location on New Hampshire Ave., 1916 (left), newspaper advertisement (center), and postcard of the farm (right). The Commonwealth Farm was a popular destination for travelers and diners.

The Commonwealth’s 120-acre farm location on New Hampshire Ave., 1916 (left), newspaper advertisement (center), and postcard of the farm (right). The Commonwealth Farm was a popular destination for travelers and diners.

In 1903, the Commonwealth bought a 120-acre farm north of Colesville. It acquired wooded land, productive fields and orchards, and a c. 1875 farmhouse from carpenter Charles Collinsgru.

Commonwealth members tended livestock and produced butter, eggs, milk, fruit, and vegetables. Always enterprising, they expanded the farmhouse and ran it as the Commonwealth Farm, an upscale country restaurant and retreat.

Through the 1930s, the farm was a popular destination for Washington elites, where the women served their “famous chicken dinners” to wives of senators and diplomats and those looking to escape the city heat in summer.

Image credits: Real Estate Atlas of Part of Montgomery County, Maryland, 1916. Edward Deets and Charles Maddox, Rockville, MD.; Advertisement, Page 4, Pt. 4, Evening Star, Washington, D.C., November 29, 1931; The Commonwealth Farm Inn, Postcard, c. 1947. Colourpicture Publishers Inc., Boston, MA. More Recent History

More Recent History

In 1946, only two members were living and most of the farmland was sold. Martha McWhirter Scheble (1883-1983), a second-generation Commonwealth member named in honor of Martha McWhirter, lived on the land until her death in 1983.

A stone retaining wall that once lined the driveway is still visible from New Hampshire Avenue.

Beltway March of 1966: A Call for Housing Justice

Forest Glen Metro Station

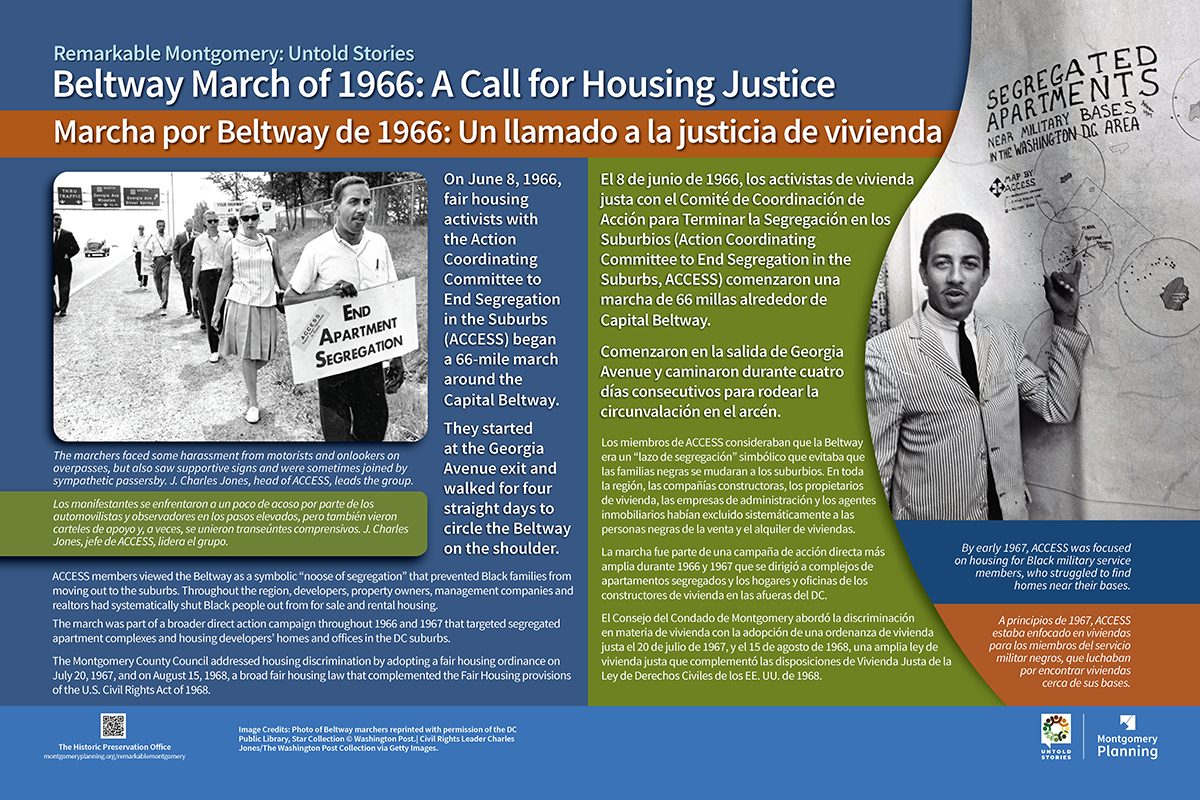

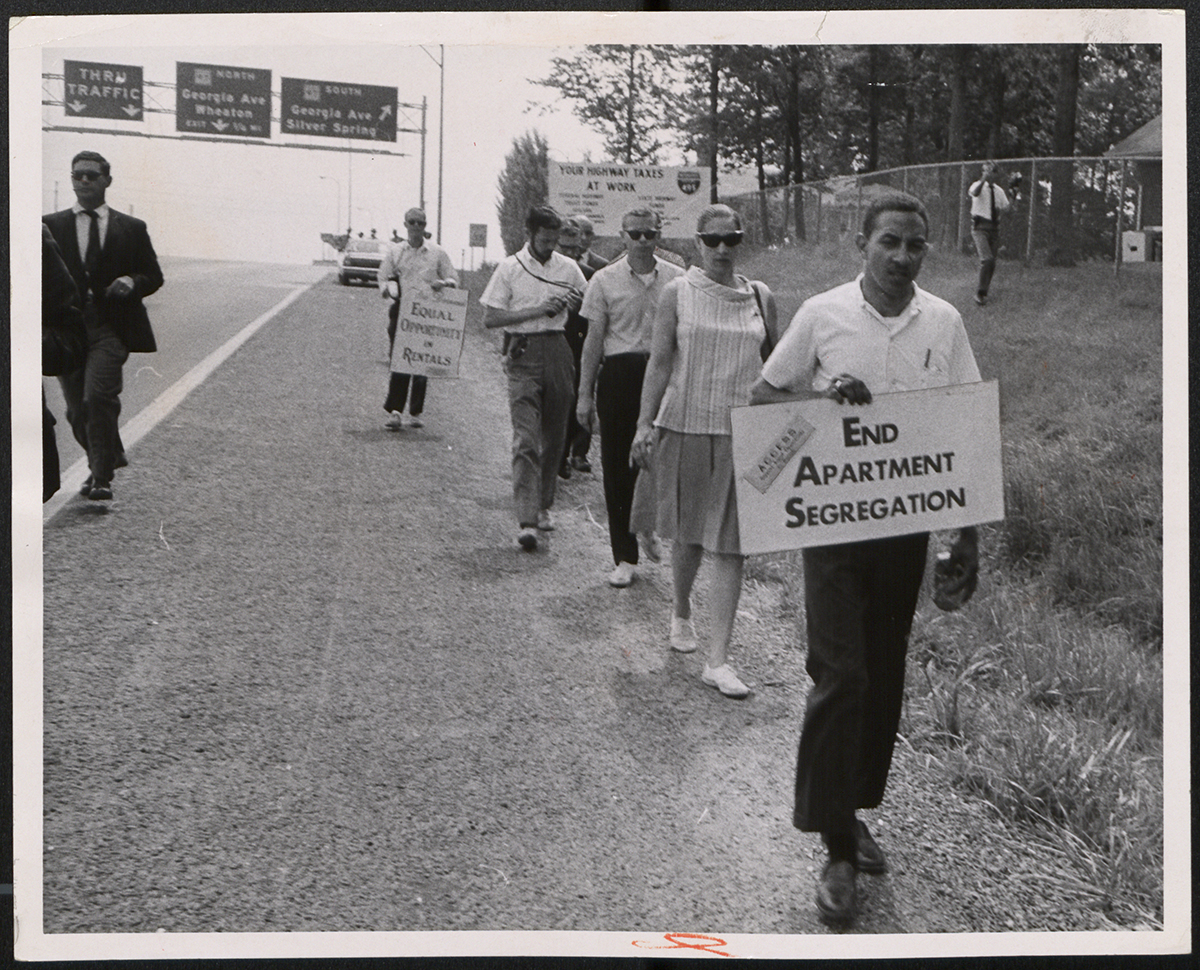

On June 8, 1966, fair housing activists with the Action Coordinating Committee to End Segregation in the Suburbs (ACCESS) began a 66-mile march around the Capital Beltway. They started at the Georgia Avenue exit and walked for four straight days to circle the Beltway on the shoulder.

On June 8, 1966, fair housing activists with the Action Coordinating Committee to End Segregation in the Suburbs (ACCESS) began a 66-mile march around the Capital Beltway. They started at the Georgia Avenue exit and walked for four straight days to circle the Beltway on the shoulder.

ACCESS members viewed the Beltway as a symbolic “noose of segregation” that prevented Black families from moving out to the suburbs. Throughout the region, developers, property owners, management companies and realtors had systematically shut Black people out from for sale and rental housing.

The march was part of a broader direct action campaign throughout 1966 and 1967 that targeted segregated apartment complexes and housing developers’ homes and offices in the DC suburbs. By early 1967, ACCESS was focused on housing for Black military service members, who struggled to find homes near their bases.

The Montgomery County Council addressed housing discrimination by adopting a fair housing ordinance on July 20, 1967, and on August 15, 1968, a broad fair housing law that complemented the Fair Housing provisions of the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1968. The marchers faced some harassment from motorists and onlookers on overpasses, but also saw supportive signs and were sometimes joined by sympathetic passersby. J. Charles Jones, head of ACCESS, leads the group.

The marchers faced some harassment from motorists and onlookers on overpasses, but also saw supportive signs and were sometimes joined by sympathetic passersby. J. Charles Jones, head of ACCESS, leads the group.

Photo credit: Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post.