History – Montgomery Modern

Modern movement architecture intentionally avoided the traditional design of revival styles that had been popular in this country since colonial times. In 1932, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City presented architect Philip Johnson’s “Modern Architecture”, a landmark exhibit that created widespread public awareness of modern movement architecture. Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock wrote an exhibit guide, coining the term International Style, to describe a modern approach to architecture, in which design is an expression of volume rather than mass, balance rather than preconceived symmetry, and applied ornamentation was to be avoided. The International Style had its origins in the Bauhaus school of Germany. Key proponents were Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, both Germans, and Le Corbusier, a Swiss architect.

Gropius and Mies were influential in the spread of International Style esthetic as heads of programs at, respectively, the Harvard Graduate School of Design and Illinois Institute of Technology. New York City was a stronghold of International style architecture in the early 1950s. Landmark projects included Lever House (1952) and Manufacturers Hanover Trust (1954), both by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore Owing and Merrill, and Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building (1954-58).

Another key factor in the dissemination of the modern approach to design was publication of Siegfried Giedion’s Space Time and Architecture (1941), which quickly became required reading for architects in training at the time. Giedion’s work highlighted organic modernism. A key force was Frank Lloyd Wright, whose designs drew inspiration from nature. While Bauhaus architects used the box as the starting point for a design, Frank Lloyd Wright broke up the box, believing every building should grow naturally from its environment. Organic modernism, which includes the work of Alvar Aalto and Eero Saarinen, incorporates rustic wood and stone, often exhibiting influence of traditional architecture of Scandinavia and Japan.

In the immediate post-war era, modern architecture was not widely accepted in the Washington metropolitan area. Colonial Revival houses in the form of Cape Cods and two-story brick houses were the predominant residential types. By this time, the revival of colonial era architecture had been popular for over a century. Traditional designed houses made good marketing sense for developers, were considered a safe venture for lenders, and a sound investment for property owners.

A small core of innovative architects were designing modernist projects. Early practitioners were Berla and Abel, best known for apartment buildings, and Charles Goodman, who designed many custom houses and residential subdivisions. Clients most receptive to modern design tended to be well-educated, and often had an artistic bent.

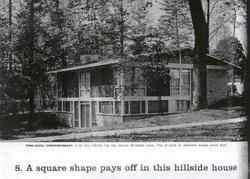

Proponents of modern design catered to conservative tastes by packaging modern design for a middle class market in suburban subdivisions. Starting in the early 1950s, Charles Goodman designed modest modern houses set into a natural landscape. The rectilinear design of the houses was softened by natural settings, made accessible by patios and balconies. Buildings were skewed on their sites to maximize views of nature and minimize views of neighboring houses, and they were banked into hillsides to preserve the natural landscape. This approach of fitting modern design into a natural setting has been dubbed “situated modernism”. The practice was supported by the Montgomery County Council’s “Anti-Bulldozer Bill”– enacted in 1957 to discourage developers from leveling the land and removing trees, as had been common practice in the immediate postwar years.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Keyes, Lethbridge & Condon worked mainly in the District of Columbia, where the firm had its office, and in Montgomery County, and to a lesser extent in Northern Virginia. All three partners had received training in the immediate postwar years from early practitioners of the modern movement–Arthur Keyes and Donald Lethbridge trained with Berla and Abel, and David Condon with Charles Goodman. During their partnership, each of the partners was also noted for remarkable individual achievements. They were all elected Fellows of the American Institute of Architects in the 1960s. Keyes, Lethbridge & Condon became an important training ground for young architects interested in residential design.

Keyes, Lethbridge & Condon set high standards for modern architecture in the Capital Region. In the District of Columbia, their projects include the Forest Industries Building (1962), at 1619 Massachusetts Avenue, and the Sunderland Building (1969), 1320 19th Street NW. In the urban renewal area of Southwest D.C., Keyes, Lethbridge & Condon won the competition for Tiber Island (1961-1963), a residential community that received an AIA national award.

A number of the modern sites in Montgomery County are the product of a collaboration between architects Keyes, Lethbridge and Condon and developer Edmund Bennett. Both entities received numerous awards for their collaborative work.In 1965, House and Home magazine named Bennett and Lethbridge among the 12 Top Performers for housing in the nation.

The Washington metropolitan area has been described as a formative arena in the promotion of builder-architect collaboration in tract housing. In the fast-paced development climate of the postwar era, an architect was most likely to succeed in the tract house market by partnering with a seasoned home builder. Such collaboration was encouraged by the professional bodies of the National Association of Home Builders and the American Institute of Architects. In addition, award-winning architects added popular appeal to tract housing. Buyers who might not be able to afford custom designed houses could still enjoy a sense of prestige in owning a house designed by a prestigious architect. Targeting an educated and worldly clientele, Bennett advertised, in 1956, that a Kenwood Park house design by Keyes and Lethbridge was “like Dior on the label of a gown.”

A common feature of many of these residential sites is a challenging terrain that, a generation earlier, had been considered undesirable for development. Bennett and Keyes, Lethbridge & Condon took advantage of the sloping terrain to offer cost-saving and space-efficient two-story plans, while preserving the feeling of “lying low on the land,” which was a characteristic of most post-World War II modern houses.

In addition to preserving natural terrain, many of the best designs from this era took care to preserve trees and vegetation. A forest floor was often conserved as an alternative to manicured lawn. Not only did they protect privacy, but trees also diminished the noise of increasingly congested roads and saved the buyer considerable expense in landscaping his property. At Potomac Overlook, branches were trimmed and a few trees cleared in order to provide a view of the Potomac River from every house.

Underappreciated and threatened with redevelopment, mid-century buildings are fragile resources as they are being demolished or renovated beyond recognition throughout the county. Too often buildings from this era have been considered outdated and obsolete, rather recognized for their historic significance and architectural distinction. As awareness of mid-century modernism grows, it is our hope that more owners and residents will understand the value of these resources to understanding our past.

Learn more about modern architect sites throughout Montgomery County by exploring the Modern Montgomery Bus Tour online map.