Project Background

August 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. This monumental action guaranteed that citizens could not be denied the right to vote on the basis of sex. While a major step forward for women, the 19th Amendment did not guarantee voting rights to all. Racial discrimination was widely practiced until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, meaning that many women of color were unable to cast ballots for decades after 1920.

With Maryland’s proximity to the U.S. Capitol, it’s no surprise that local women played a significant role in the decades-long fight for voting rights.

Below, we highlight some of the findings from Historic Preservation staff’s research into Montgomery County’s role in the women’s suffrage movement. This research marks one phase in an ongoing effort to document the county’s history of social and political activism and to identify historic sites and communities associated with this work.

This timeline includes relevant statewide developments that impacted women and suffrage activism in Montgomery County, and includes the work of African American suffragists around the state, whose work in Montgomery County is less well documented.

Major Milestones

1867

In Baltimore, Lavinia Dundore organizes the Maryland Equal Rights Society, considered the state’s first women’s suffrage club. It includes Black and white men and women who work together for expanded voting rights, but their efforts do not make significant headway in a state strongly opposed to their cause.

1870

The Fifteenth Amendment is ratified, granting voting rights to Black men. A bitter fight over ratification splits the suffrage movement, and Black suffragists begin to be pushed out of majority-white suffrage organizations in order to attract support from white male legislators. Suffragists work primarily in racially segregated organizations for the duration of the movement.

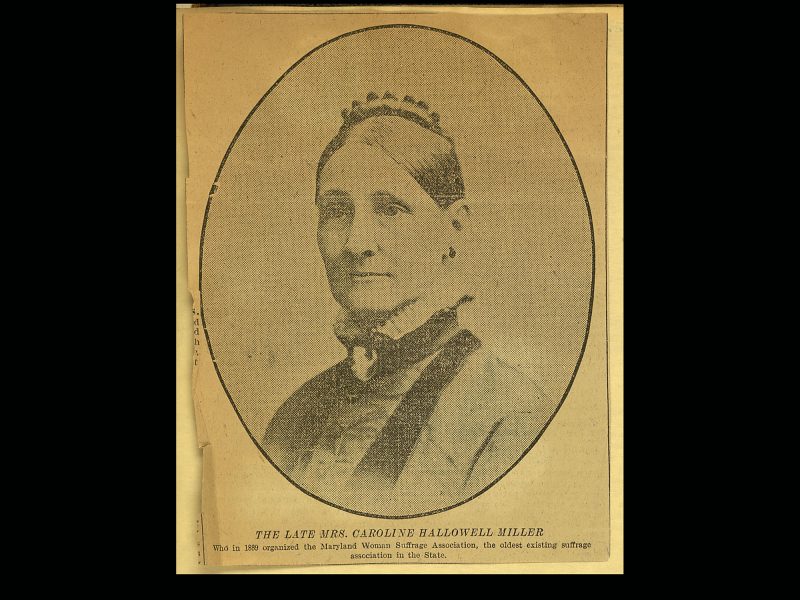

1889

At her home in the Quaker village of Sandy Spring, Caroline Hallowell Miller convenes a small group of friends to begin a women’s suffrage society. Miller was an engaging public speaker who addressed local audiences and delivered humorous and compelling speeches at national suffrage conventions through the 1880s. The initial group includes thirteen members and meets at Miller’s home, Stanmore (now demolished), and periodically at the Sandy Spring Lyceum, now part of the Sandy Spring Historic District (Master Plan Historic District #28/11).

Miller’s group formed the basis of the Maryland Woman Suffrage Association, which she led as president until she was succeeded c. 1894 by fellow Sandy Spring resident Mary Bentley Thomas. Thomas led the Maryland Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) through its early years as suffragists from Baltimore City joined and began to band together as one organization.

1905

On the November ballot, Marylanders consider the Poe Amendment, a ballot initiative that would introduce a grandfather clause and an understanding test intended to disenfranchise Black male voters. This is the first of three attempts to implement Jim Crow voting restrictions across the state by ballot question.

The Suffrage League of Maryland, established in 1904, organizes Black voters across the state to reject these repeated attempts at disenfranchisement. Founding president W.M. Alexander describes their purpose in 1904 as “to kill Jim Crowism” in Maryland and prevent it from taking root as it had throughout the South.

In October, the West Washington District Conference of the A.M.E. Zion Church meets in Rockville and adopts a resolution condemning the Poe Amendment and calling Black Republicans to take action to defeat it. The Poe Amendment is rejected at the ballot box, as are subsequent statewide disenfranchisement measures.

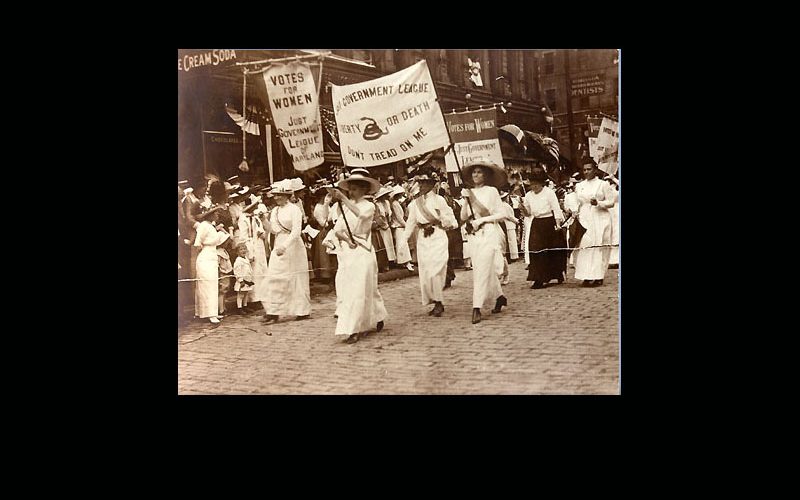

1909

Baltimore social worker Edith Houghton Hooker forms the Just Government League, a new suffrage organization committed to statewide grassroots organizing and more aggressive tactics including increased public engagement through street speeches and demonstrations.

1912

Throughout August, a Just Government League field organizer campaigns across Montgomery County, holding mass meetings in Kensington, Garrett Park, Gaithersburg, Travilah, Damascus, Laytonsville, and Clarksburg.

By November, a Montgomery County branch of the Just Government League has formed with 289 members. Meetings are held that fall in Gaithersburg and Garrett Park. Creszensa White of Barnesville is elected president by early 1913.

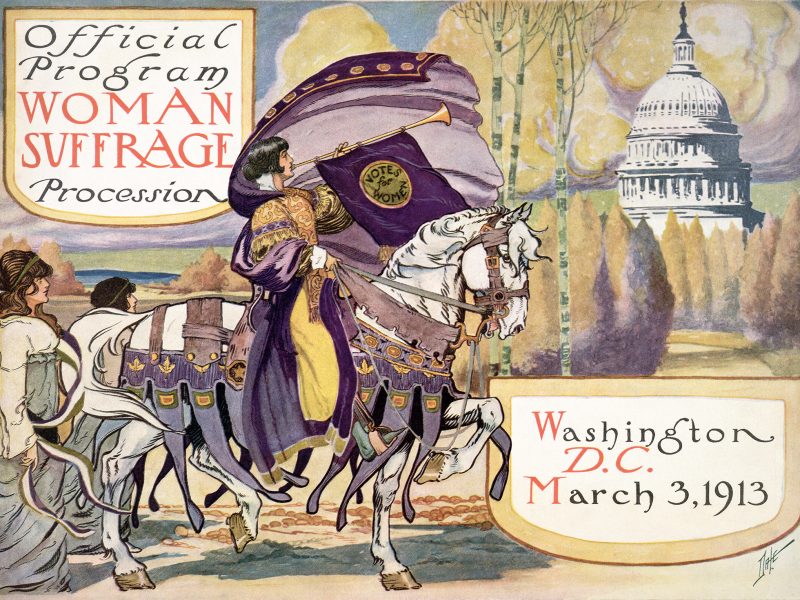

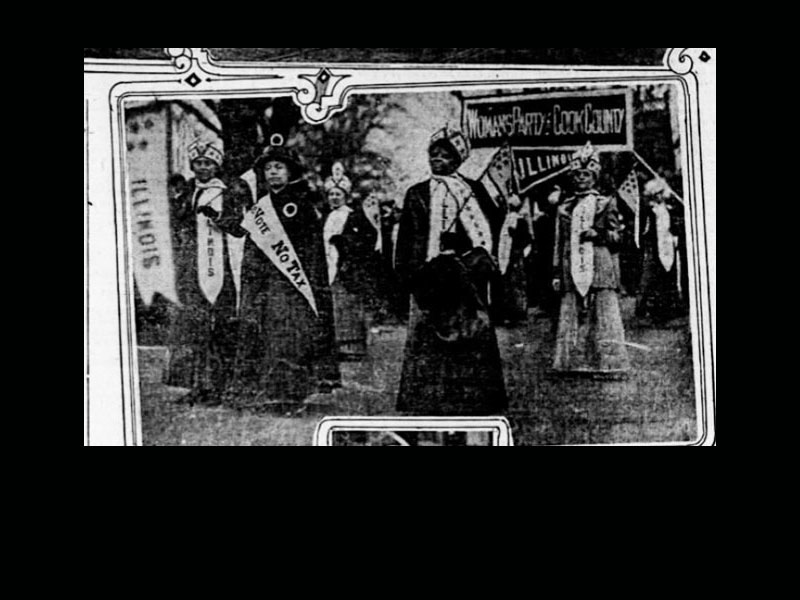

March 3, 1913

The national Woman Suffrage Procession brings thousands to Washington, D.C. on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. The marching crowd includes a large delegation of students and teachers from the National Park Seminary, some of whom served as ushers to parade herald Inez Milholland.

Alice Paul had carefully orchestrated the parade, planning in detail the order in which participating groups would march. At Paul’s order, Black suffragists were directed to march at the back of the parade, behind the men. This would draw the least attention to their presence and risk the least upset to the Southern Democrats the suffragists were courting. Illinois suffragist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells refused this directive and walked with the Illinois delegation. The young founding members of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority also marched, in one of their first public actions.

Midway through the procession, onlookers close off the parade route and begin harassing and trampling the marchers. Chevy Chase residents Gertrude and Eugene Stevens carry the banner of the Montgomery County Just Government League and later recount the indifference of the police to the assault underway.

June 22, 1913

The Chevy Chase Equal Suffrage League forms with 36 founding members. The League elects officers and begins to meet regularly at members’ homes around Chevy Chase. That fall, they host the statewide Just Government League at the Chevy Chase Library for their semi-annual meeting, at which National American Woman Suffrage Association President Dr. Anna Howard Shaw is the keynote speaker. In November, an open-air meeting in Chevy Chase Circle features national suffrage campaigners Jessie Hardy Stubbs and Jeanette Rankin of Montana, who in 1916 becomes the first woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Much of the work in Chevy Chase was spearheaded by Minnie E. Brooke. Brooke owned a gift shop in D.C. and ran the Brooke Farm Tea House from her home in Chevy Chase, No Gain (Master Plan Historic Site 35/69). She was a dedicated activist, delivering weekly speeches at suffrage street meetings in the District, hosting meetings at her home, and later campaigning across the country for the cause.

Summer 1915

The Just Government League embarks on a summer pilgrimage through Montgomery County. In these traveling campaigns, suffragists journeyed by foot or by covered wagon to rural communities, drawing curious crowds, raising money and recruiting supporters. For a detailed account of campaign tactics, read Edna Story Latimer’s report in the June 1914 “Pilgrim’s Edition” of the Maryland Suffrage News.

The Maryland Suffrage News reported that the caravan traveled from Baltimore to Laurel, and from there to Spencerville, Brookeville, Barnesville, Poolesville, Darnestown and Garrett Park.

Fall 1915

Black suffragists in Baltimore organize the Progressive Suffrage Club and begin holding public meetings, led by club president Estelle Hall Young. Members come from local civic and social organizations already working on neighborhood issues including childcare, education, and care for people living in poverty. Black clubwomen also confronted residential segregation and racial discrimination.

Amid the Jim Crow voting restrictions sweeping the South, writers for the Afro-American would later express the hope that adding Black women voters to the rolls would make it “more difficult to keep black men and black women away from the polls than black men by themselves.”

1916

The 1916 federal and statewide elections present women with an opportunity to defeat anti-suffrage candidates around the country.

At an August 15 open-air meeting in front of the Rockville courthouse, Minnie E. Brooke and fellow members of the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage launch a campaign against Maryland’s Sixth Congressional District Representative David J. Lewis, who is running for the U.S. Senate and opposes federal action on women’s suffrage. Using tactics proven in past suffrage pilgrimages, Brooke embarks on a “whirlwind automobile campaign” across the Sixth District accompanied by Harriet White Peters, a fellow Chevy Chase suffragist.

Minnie E. Brooke is next deployed to Chicago by the National Woman’s Party to take charge of their street meetings in the lead-up to the election, where she reports being attacked by hostile crowds.

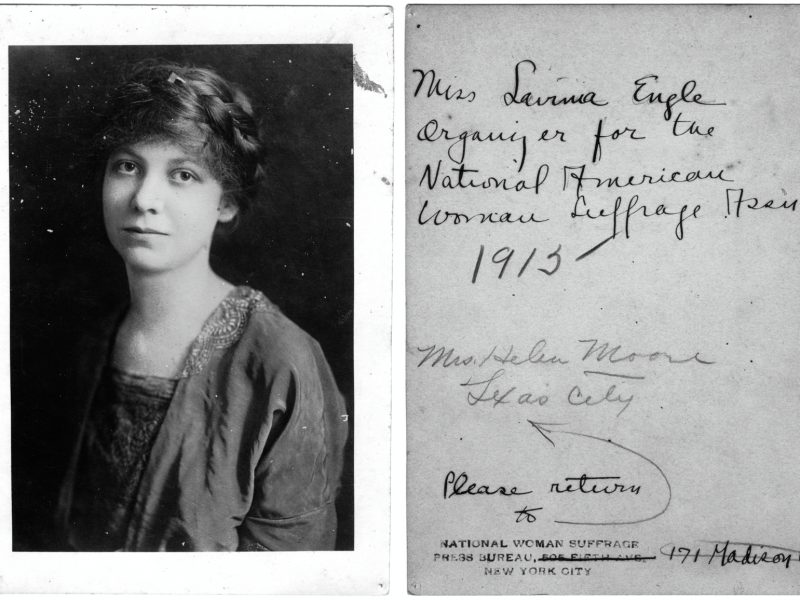

Lavinia Engle, a Forest Glen native and national organizer for the National American Woman Suffrage Association, was sent to campaign in Texas, having previously organized in Florida (1914), North Carolina (1914), South Carolina (1914), and Alabama (1915).

1917

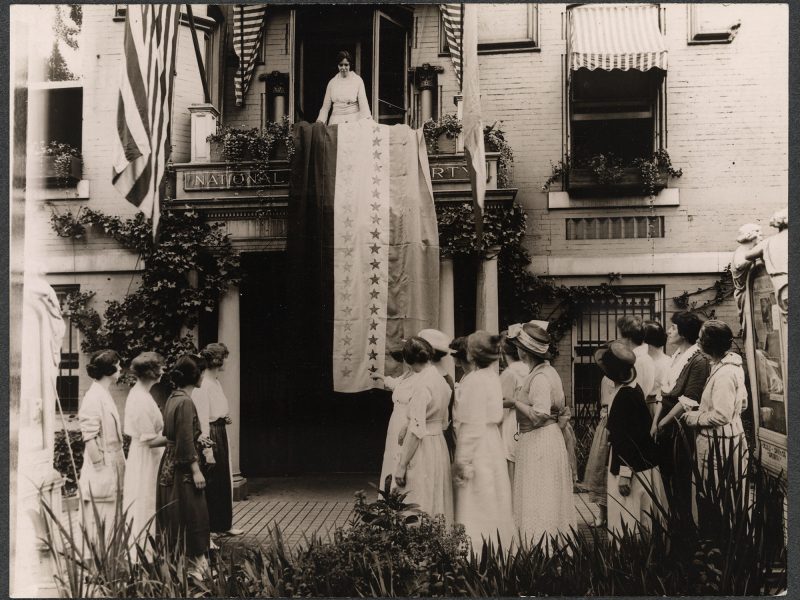

In January, women of the Congressional Union begin picketing the White House in response to a dismissal of their demands by recently re-elected President Woodrow Wilson. The statewide Just Government League eagerly supports these militant tactics, but some Maryland women feel this action to be too radical, especially after the US enters World War I in April. Several local branches of the Just Government League break away, including the Montgomery County branch.

Jessie Ross Thomson of Garrett Park, formerly president of the Montgomery County Just Government League from 1914-1916, is elected to lead a new and more moderate statewide organization, the Woman Suffrage League of Maryland.

After the U.S. enters World War I in April, conservative suffragists largely dedicate themselves to supporting the war effort. Local women organize war work through the Montgomery County Council of Defense and form aid committees led by women from Boyds to Olney.

Meanwhile, radical women continue to protest at the White House, facing violence from hostile crowds, arrest, and jail time.

1918

At its annual meeting held in Sandy Spring on May 17, the Montgomery County Federation of Women’s Clubs adopts a resolution endorsing women’s suffrage, the first county federation in Maryland to do so.

At the annual meeting of the Woman Suffrage League of Maryland, held June 5, suffragists review work undertaken to support the war effort, including committees on the Red Cross, overseas hospitals, food conservation, and Liberty Loans. President Jessie Ross Thomson declares:

When the whole story of women’s part in this war is written the men who are opposing suffrage for women will hang their heads in shame, for they will be proved disloyal to their wives, mothers, and sisters.

1919

In January, Kate Winston of Chevy Chase is arrested and sentenced to five days in district jail for her role in the watchfire demonstrations, in which National Woman’s Party members burned copied of President Wilson’s speeches at public buildings including the White House. Minnie E. Brooke is later decorated by the National Woman’s Party for her role in the protests.

That April, the Maryland Federation of Women’s Clubs finally adopts a resolution endorsing women’s suffrage. The national General Federation of Women’s Clubs had endorsed suffrage five years previously, and Maryland’s Federation was among the last to declare their support.

That summer, both the U.S. House and Senate pass the federal woman’s suffrage amendment, sending it to the states for ratification. 36 states needed to ratify the 19th Amendment for it to be adopted. Only 13 states would need to vote against the amendment to defeat it. Most Southern states, including Maryland, were expected to reject it.

January 1920

Maryland’s legislative session begins. Suffragists organize a coordinated campaign as the General Assembly takes up the question of ratification. They have by now secured the endorsement of organizations representing diverse groups across the state, including the Maryland Association of Graduate Nurses, Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Friends’ Equal Rights Association, Council of Jewish Women, and the Women’s Trade Union League of Baltimore.

February 17, 1920

The Maryland General Assembly decisively rejects ratification of the 19th Amendment: the House by a vote of 64 to 36 and the Senate by a vote of 18 to 9. Each Montgomery County delegate in the House votes to reject ratification. The General Assembly later adopts a Joint Resolution condemning states which have previously ratified the amendment and urging those who have not yet voted to reject it.

May 1920

Maryland women begin to organize a branch of the League of Women Voters. Forest Glen suffragist and National American Woman Suffrage Association organizer Lavinia Engle is charged with establishing citizenship schools around the state to instruct local leaders, who will in turn train women in their communities to vote.

W.E.B. Du Bois, writing in The Crisis, urges Black communities to prepare for women’s suffrage and the attempts to suppress women’s votes that would follow:

Are we getting ready for this mighty change? Are we consulting and laying plans? The white South is.

August 1920

On August 18, Tennessee becomes the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment. On August 26, the amendment is certified by the U.S. Secretary of State and is officially adopted as part of the U.S. Constitution.

September 1920

Immediately after ratification, suffragists direct their efforts to registering women to vote in time for the fall presidential election.

Estelle Young, president of the Progressive Suffrage Club, vows to register and turn out Black women voters in response to state legislators’ efforts to keep them from the ballot box. In the Afro-American, she explains that:

We must register in order to vote, and we must vote in order to rebuke those politicians.

Young reportedly travels to Montgomery County in late August or early September to organize new chapters of the Progressive Suffrage Club. As word reached Black county residents of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the Afro American reports that “enthusiastic overflow meetings” gathered to hear Young speak.

Montgomery County Democratic women meet at the home of Clara Wilson in Kensington to organize their work and prepare for voter registration efforts. By October, the Washington Post reports that 4,876 women have registered to vote in Montgomery County, including approximately 1,000 women of color.

November 2, 1920

Maryland women vote in their first presidential election.

Post-1920

Recognizing women as an important new voting bloc, Maryland’s political parties begin appealing to women and integrating them into party leadership through the 1920s and 1930s.

On August 10, 1921, Montgomery County Republicans gather in Rockville to choose candidates for statewide and local office. The convention backs Rosalie Small, of Silver Spring, for the State Central Committee, the lone woman chosen among the recommended candidates. Women at the convention gather to form the Montgomery County Women’s Republican Club, and Chevy Chase suffragist Gertrude Stevens is elected as corresponding secretary.

Entrenched racial segregation meant that white and Black members of the same political parties often worked separately.

The Montgomery County Colored Republican Club, organized by 1900, elected women to leadership positions by 1928. Maude McElroy of Rockville served as Secretary, while Elsie S. Horad of Wheaton and Henrietta Cooper of Rockville served on the Executive Committee.

In Southern states where racially discriminatory voting restrictions are legally sanctioned, Black women do not gain equal access to the ballot until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

2020

100 years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, women are reflecting on the mixed legacy of the suffrage movement and the work remaining to gain social, political, and economic equality. Women activists continue to lead campaigns for progressive reform and social justice.