Written by Casey Anderson and Nicholas Holdzkom

Design of the built environment strongly influences our quality of life. The pattern of development across a city, county, and region; the configuration of neighborhoods and districts; and the architecture of individual buildings collectively shape our perception of places and influence how we choose to travel, recreate, and socialize.

This series has explained how Thrive Montgomery 2050 addresses design at each of these scales. The post on compact growth outlined a countywide framework for concentrating development along corridors. The post on complete communities addressed design at the level of neighborhoods and districts, describing how a mix of uses and amenities can be built – literally and figuratively – on the foundation established by a compact footprint. This post discusses the fine-grained details of blocks and individual development sites, the architecture of buildings and landscapes, and the configuration of streets and other public spaces.

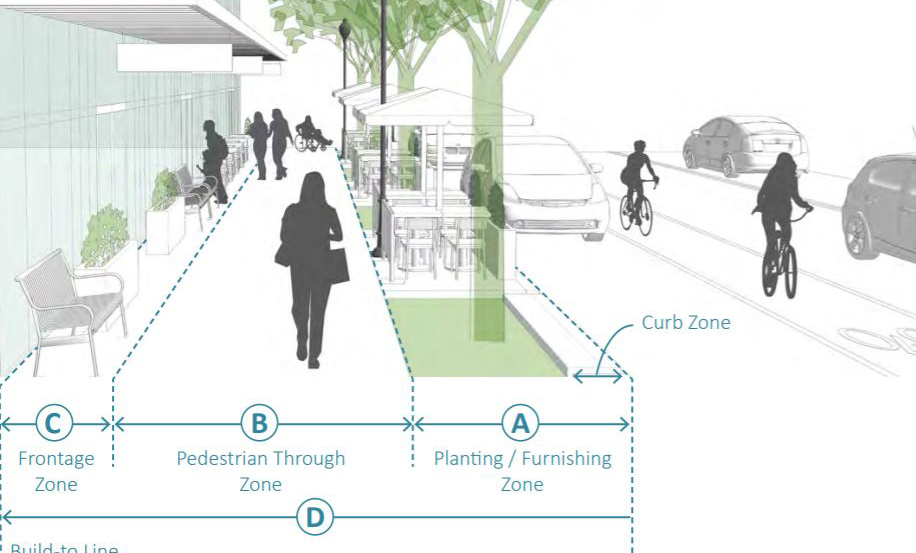

Design at this more granular level serves functional and aesthetics purposes. Functional considerations dictate how structures are built and how they connect to the sidewalks, streets, and spaces around them to facilitate movement, social interaction, and physical activity. Aesthetic aspects of design, along with the integration of arts and cultural elements, influence how streets, buildings, and spaces look and feel to create beauty and a sense of place. Arts and cultural practices touch every corner of life and are one of the most visible indicators of the social values and diversity of a place.

Designing for cars: wide streets, dispersed buildings, and lots of parking

The Wedges and Corridors plan envisioned a variety of living environments and encouraged “imaginative urban design” to avoid sterile suburban sprawl. Unfortunately, design approaches intended to serve many functional objectives and aesthetic aspirations soon succumbed to an emphasis on the convenience of driving and the assumption that different land uses, building types, and even lot sizes should be separated. Over time, these priorities produced design approaches that failed to create quality places with lasting value.

Automobile-oriented design has led to developments in many parts of the county where the pedestrian feels unwelcome and buildings do not relate to the street.

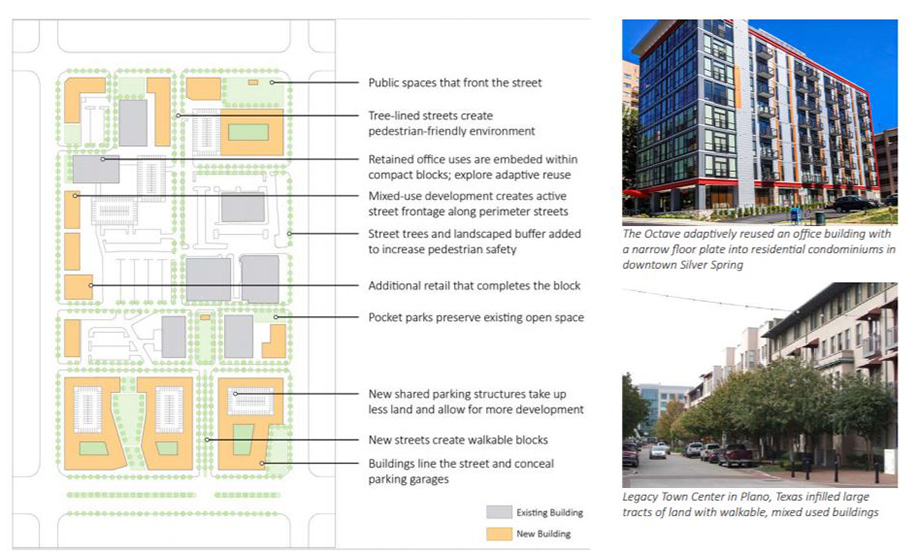

Buildings designed to accommodate single uses, while less expensive when considered in isolation, created an inventory of structures that are inflexible and costly to reuse. Malls, office parks, and other large, single-use buildings are difficult to repurpose and the high cost of adapting their layouts to meet new spatial needs due to technological shifts, demographic changes, and market preferences shortens their useful lives and makes them less sustainable.

Land use regulation for a post-greenfield community

As Montgomery County’s land use has matured to where opportunities on undeveloped land have been nearly exhausted, a new approach, more suited to infill and redevelopment, is required. When the subdivision of farmland was the primary means for accommodating growth, the focus of land use regulation was on the entitlement process, which allocates development rights and responsibility for the provision of basic infrastructure such as roads and sewer pipes. The form and orientation of buildings to each other and to the public realm was a secondary consideration.

These rules are well-suited to standardized, cookie-cutter subdivisions but poorly adapted to the design of distinctive projects that respond to their surroundings and the needs of increasingly constrained development sites – to say nothing of celebrating local geography, history, and culture. We can no longer afford to ignore the attributes of neighborhood and site design that strongly influence perceptions of the quality and potential of a place.

Are you saying that we need to rewrite our zoning code from scratch?

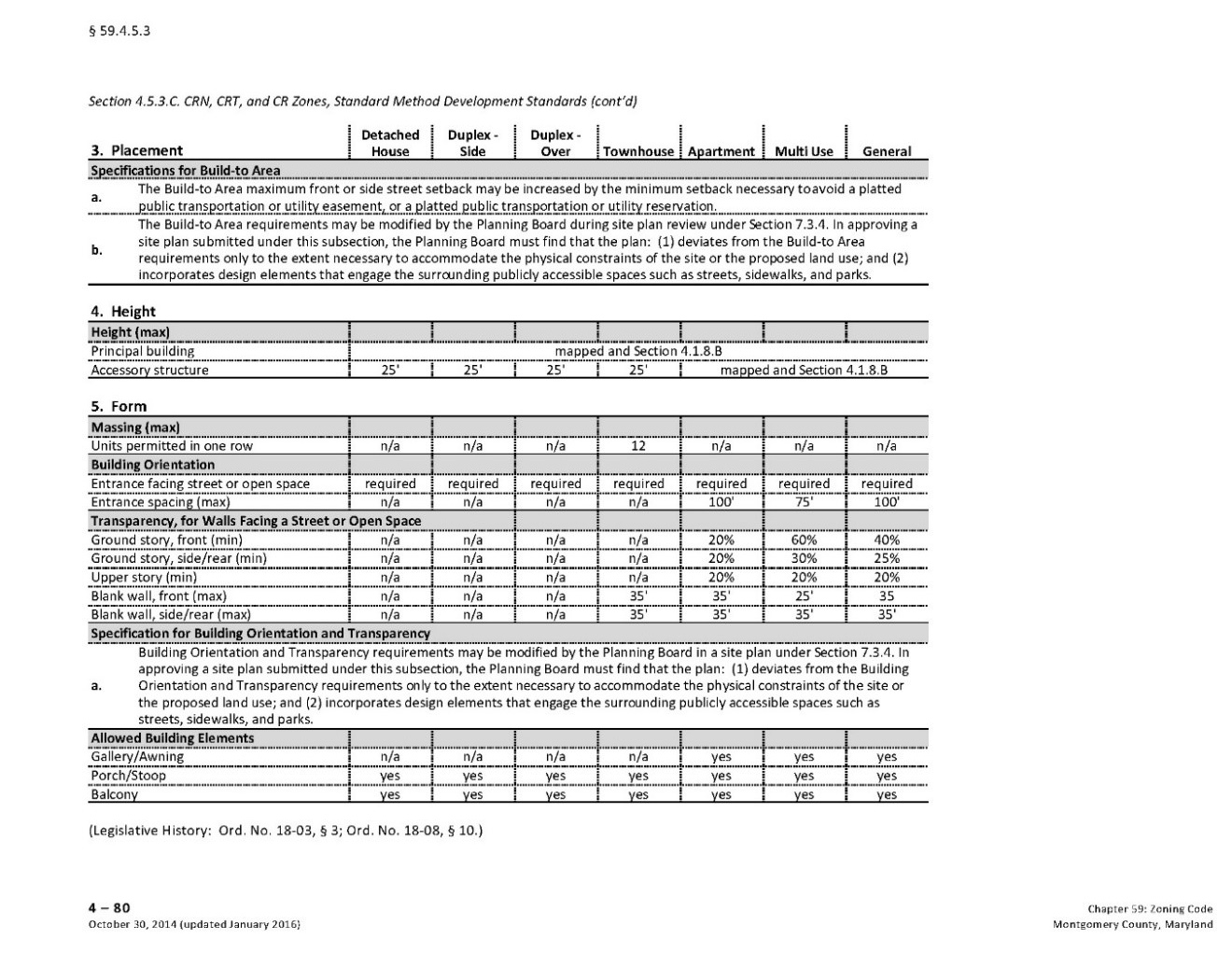

The short answer is no. Our code already has some form-based standards included in the Commercial Residential (CR) zones, as shown in the table below. These standards establish basic requirements for ensuring that buildings address the street and that ground floors of large buildings do not present blank walls to the public realm. These requirements are simple but effective in ensuring that new, larger buildings do not put a damper on street life in business districts. Thrive Montgomery 2050 proposes adding similar form-based standards beyond the areas designated for the most intensive forms of development. These updates can be implemented through zoning text amendments to supplement and update the existing code.

Sometimes a more detailed set of recommendations is needed, and land use plans for individual neighborhoods and districts can provide them. Recently approved plans for Bethesda, Rock Spring, White Flint and Grosvenor all include form-based guidance that accounts for local geography, economic conditions, history, and community needs.

Support for arts and culture as contributors to quality of place

Montgomery County has evolved into one of the most diverse jurisdictions in the nation and our arts and culture sector is impressive in its scope and depth. Taken as a whole, the sector would be the sixth-largest employer in the county. While the county makes significant investments in arts and culture, these investments are not always equitably distributed. Emerging organizations that support underserved communities often lack the funding and base of support enjoyed by some of their more established counterpart. Artists and arts organizations cite the lack of affordable living, working, and sales spaces as a major challenge. The field of public art has been expanding to embrace a wider range of approaches including civic and placemaking practices, but the county’s art programs lag in their ability to apply these approaches.

Thrive Montgomery proposes three main strategies to address these issues:- An emphasis on the role of design in creating attractive places with lasting value that encourage social interaction and reinforce a sense of place. This requires design guidelines and regulatory tools that focus on the physical form of buildings, streets, and spaces. It replaces vague concepts such as “compatibility” with clear standards for form, site layout, setbacks, architecture, and the location of parking, and removes regulatory barriers and facilitates development of “missing middle” housing types while adopting context-sensitive design guidance for all master planning efforts. This means that land use regulation should become somewhat more prescriptive but also more predictable.

- Promotion of retrofits and repositioning to make new and existing buildings more sustainable and resilient to disruption and change. Thrive Montgomery recommends encouraging sustainability features in both new public buildings and large private development projects to help mitigate the effects of climate change and promoting cost-effective infill and adaptive reuse strategies to retrofit single-use commercial sites such as retail strips, malls, and office parks into mixed-use developments. It also recommends incentivizes forthe reuse of historic buildings and existing structures to accommodate the evolution of communities, maintain building diversity, and preserve affordable space.

- Support for arts and cultural institutions and programming to celebrate our diversity, strengthen pride of place and to make the county more attractive and interesting. This involves promoting public art, cultural spaces, and cultural hubs as elements of complete communities. Thrive Montgomery 2050 also calls for eliminating regulatory barriers to arts and culture with a focus on economic, geographic, and cultural equity. It encourages property owners, non-profit organizations, and government agencies to maximize use of public spaces for artistic and cultural programming, activation, and placemaking. Finally, it argues that public art should be incorporated into the design of buildings, streets, infrastructure, and public spaces so that residents can experience it in their daily lives.

Learn more about the Design, Arts and Culture chapter in Thrive Montgomery 2050.

A future post will elaborate on the need for more form-based standards to reduce uncertainty and subjectivity in evaluating the “compatibility” of infill and redevelopment projects as an important step in making land use regulation more equitable in addition to elevating its quality.

About the authors

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

Nick Holdzkom is a Senior Planner/GIS Analyst in the Montgomery County Planning Department’s division of Research and Strategic Projects. In this role, Nick supports the division in GIS analysis and map products, and assists in master plan analysis, including existing conditions, build-out scenarios, and economic feasibility. Nick has recently managed studies such as the Master Plan Reality Check, a project on public facility colocation efforts, and a countywide mixed-use development study. He received a Bachelor of Science in Geography, with a concentration in GIS, from North Carolina Central University and a Master of Arts in Geography and Urban Planning, with a concentration in GIS, from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He is married and lives in downtown Silver Spring with his wife their adorable, though generally bad, cat.