Tucked in among subdivisions and stream valleys, the County’s historically black settlements reflect a history that traces back to the County’s earliest days.

In 1790, local tobacco plantation were worked by slaves, who made up one third of the County’s population. Josiah Henson, whose memoirs inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, described the conditions.

“In a single room were huddled, like cattle, ten or a dozen persons, men, women, and children. All ideas of refinement and decency were, of course, out of the question.”

But alongside planatations, the County’s Sandy Spring Quaker community freed its slaves in 1770, conveying to them land for a church and dwellings. Sandy Spring would also become a key stop on the Underground Railroad.

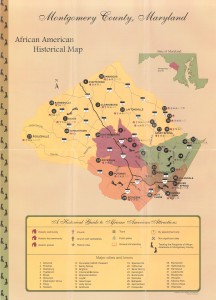

After the Civil War, in 1870, the black population was still about a third of the County—36 percent. Freed slaves bought or were given land, sometimes by former owners—and transformed scrub fields into agricultural homesteads. Over 40 African-American communities have been identified, often anchored by churches that were used as schools and social centers, surrounded by log and later frame houses.Today, many of these communities retain their strong cultural identification, associated with generations of families. As the County developed, these agricultural communities were surrounded by new development, yet they live on, as tight-knit and distinct communities. Some like Lyttonsville, celebrate that history. Others, like Tobytown, struggle with it.

Visit here, for more Black History Month events in Maryland