By Benjamin Kraft and Casey Anderson

Businesses and multifamily housing along Fenton Street in downtown Silver Spring.

The conventional story about development and displacement goes something like this: new luxury housing gets built in a neighborhood, driving up rents for existing residents who then must leave to find less expensive housing elsewhere. To be sure, displacement does happen and it can be a serious problem, but our Neighborhood Change research shows that this conventional story of displacement doesn’t correspond to what is happening in Montgomery County. Specifically, the study shows that displacement of lower-income residents is not inevitable, and that where it occurs is not driven by new housing development. In fact, displacement is associated with the failure to build new housing in neighborhoods experiencing an increase in demand. Our study further suggests that building more housing, especially with policies like Montgomery County’s moderately priced dwelling unit (MPDU) program in place, promotes inclusive growth, meaning growth that makes room for people of all incomes.

Townhomes on King Farm Boulevard

Our research found that six of Montgomery County’s census tracts have experienced inclusive growth between 2000 and 2019, meaning that they met three criteria:

- The number of residents with incomes that were at least twice the federal poverty level increased by at least 10%1

- The share of residents with incomes below twice the federal poverty level fell by at least 5%, AND

- The number of residents with incomes below twice the federal poverty level went up.2

The first two criteria indicate that a neighborhood is getting wealthier, since the number and proportion of people with higher incomes are growing. The third criterion indicates that low-income people are also moving into the neighborhood. All three of these things can happen at the same time. That is, as a neighborhood expands economically and attracts high- and middle-income residents, it can also add lower-income people.

So where are these inclusive neighborhoods?

They happen to be some of the county’s most prominent. Downtown Silver Spring, Bethesda, and Rockville all qualify as inclusive growth tracts. So do the King Farm neighborhood in Rockville and the north end of downtown Wheaton.3

These neighborhoods have one main thing in common: They all built a lot of new housing between 2000 and 2019. As a Washington Business Journal article highlighting the study notes, “Neighborhoods that experienced a rise in overall affluence, but without pushing out their lower-income segments, have on the whole gained at least an order of magnitude more net new housing units than those experiencing displacement and other unwelcome trends.” In fact, the county’s six inclusive growth neighborhoods amount to only 3% of the county’s 215 census tracts but accounted for 20% of the net new housing built in the county over the study’s time period. Neighborhoods that grew inclusively added 18 times more housing per tract than those growing with displacement and 68 times more housing per tract than those seeing worsening concentrations of poverty.

These neighborhoods prove that displacement is neither inevitable nor caused by housing development. In fact, the study provides strong evidence that housing creates the opposite effect.

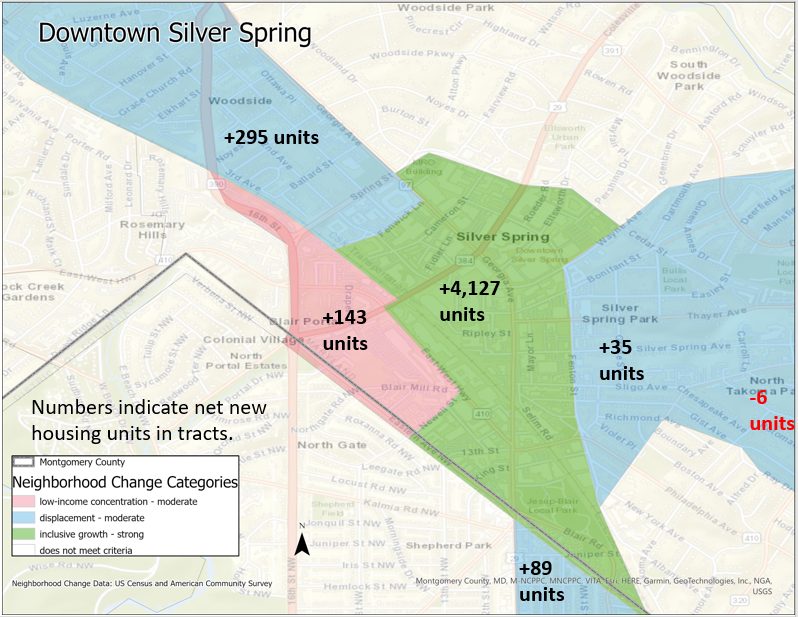

Downtown Silver Spring is an illuminating example of what inclusive growth looks like. It grew more inclusively than any neighborhood in the Washington DC metro region, adding over 900 low-income residents between 2000 and 2019. In addition to becoming more economically inclusive, downtown Silver Spring also grew in a racially and ethnically inclusive way: it added almost as many Black residents (2,203) as white residents (2,254), and overall added more people of color than white residents.

Fostering this type of diversity wouldn’t be possible without adding more housing. As the map below shows, Silver Spring added over 4,000 housing units between 2000 and 2019, while its neighboring tracts—especially those seeing displacement—added far fewer.

The relationship between housing and opportunities for people of color is not unique to downtown Silver Spring. It applies everywhere in Montgomery County.

The two scatterplots below show that housing growth and the population of Black and Latino residents are positively correlated at the tract level, meaning that in the average tract, adding housing is associated with more—not fewer—Black or Latino residents. For Black residents, the relationship is statistically significant, while for Latino residents it hasn’t quite reached that level of certainty. Even so, the chart allows us to say at minimum that new housing does not cause displacement of people of color—as is commonly thought.

Relationship between Black and Latino population growth and housing growth in census tracts in Montgomery County.

Of course, simply building housing is not a silver bullet that will solve all affordability or displacement problems. While much of the new housing accounted for in this study is regular market-rate housing, Montgomery County’s strong affordable housing programs—especially the moderately priced dwelling unit (MPDU) program—undoubtedly make such inclusive growth possible. People making under 200% of the federal poverty cannot likely afford much of this housing on the open market (although many residents without income-restricted units in downtown Silver Spring are likely cost-burdened by housing). This and other affordability programs should continue and be expanded. And while building alone won’t solve the affordability problem, this point underscores what an important component it is to the solution: The MPDU program is only triggered when new housing is built.

Redevelopment doesn’t mean replacing affordable housing with luxury apartments

Downtown Bethesda can help to illuminate how our affordable housing programs contribute to inclusive growth. First, while the two central downtown Bethesda census tracts show diverging neighborhood change trends (one is experiencing inclusive growth while the other is experiencing displacement; this can be viewed on the neighborhood change interactive map), aggregating these two tracts would place them in the inclusive growth category. If the four tracts included in the Bethesda’s 2017 master plan are aggregated, the entire area would narrowly miss being classified as inclusive growth; it still gained 385 lower-income people overall.

This inclusivity has been possible partly due to the MPDU program. Since Bethesda’s master plan, 1,843 new housing units have been built in downtown Bethesda, 270 of which were MPDUs. To gain these affordable units, only 14 existing units—most of which were initially built as residential but used as office or other commercial units by the time of their redevelopment—were demolished. These kinds of net housing gains—both market rate and affordable—make inclusive growth possible even in an expensive area like Bethesda and help to deconcentrate poverty by giving lower-income families opportunities to live in higher-income neighborhoods.

None of this is to deny the existence of displacement. As the Neighborhood Change study shows, displacement is happening to a limited extent in Montgomery County and is a severe problem in the District and Arlington and Alexandria in Virginia.

Even without displacement, the changing character of growing neighborhoods can be unsettling. Lower-income people and people of color can begin to feel unwelcome in their neighborhoods even if they are not literally being pushed out. To be fully socially and culturally inclusive, we must continue to strengthen our affordable housing programs and preserve culturally significant private and public spaces. Also, adding market rate and affordable housing in areas that are not susceptible to displacement—often because they are already predominantly affluent—will go a long way to preventing further displacement in areas that are changing by lessening housing pressure there.

Montgomery County prides itself on its diversity, and for good reason. The county is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse counties in the U.S. The same unfortunately cannot be said of many of its neighborhoods, which remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and income. Ultimately, if we want our neighborhoods to be more diverse in a way that reflects the diversity of our county and some of our signature downtowns, we must grow and add more housing to accommodate this growth. Otherwise, it’s a zero-sum game – someone must leave for someone else to move in. Growing inclusively means making space for everyone.

1 The federal poverty level for a family of four was $51,500 in 2019.

2 See full explanation of study methodology.

3 Although downtown Wheaton’s core census tract does not meet the neighborhood change criteria, it did add residents of all income levels in significant numbers. In fact, it increased its middle-high income population by over 70% while also increasing its share of low-income residents by over 5%. This tract joins the tract containing Downtown Crown in Gaithersburg as the only two in Montgomery with such significant changes in both directions. Each of these tracts added over 1,400 housing units between 2000 and 2019.

About the authors

About the authorsBen Kraft is a research planner in the Research and Strategic Projects Division. His research and planning work focuses on topics related to the economy and employment. Ben has a Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning from Georgia Tech and a Master’s degree in Urban Planning from the University of Michigan.

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

Tel U

what is the vision and mission of the MPDU program?

Lisa Govoni

Hi Tel U –

The Council enacted the county’s Moderately Priced Dwelling Unit (MPDU) law in 1973 with several objectives. The law is aimed at furthering the objective of providing a full range of housing choices for all incomes, ages and household sizes. In particular, the law imposes a requirement on the construction of affordable housing to meet the existing and anticipated needs for low and moderate-income housing and ensure that moderately priced housing was dispersed throughout the County. It provides incentives to encourage the construction of moderately priced housing by allowing optional increases in density including the MPDU density bonus to offset the cost of construction.

Learn more here: https://montgomeryplanning.org/planning/housing/ or https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/DHCA/housing/singlefamily/mpdu/index.html