A once-segregated public school can teach future generations about an important chapter in county history

By: Kacy Rohn and John Liebertz

Locally designated African American historic sites around Montgomery County highlight the central role of African Americans in the story of the county and the nation. These sites include places where free and formerly enslaved African Americans lived, worked, worshipped, and buried their loved ones throughout the county.

Another site may soon be designated. Montgomery County Historic Preservation staff are considering whether the former Edward U. Taylor Elementary School in Boyds should be added to the county’s Master Plan for Historic Preservation. The recently approved and adopted MARC Rail Communities Sector Plan recognized the school as a neighborhood landmark and recommended that it be considered for historic designation. The Montgomery County Board of Education built the Taylor School in 1952 as an elementary school for African American students at a time when racial segregation of public schools was still legally sanctioned.

The former Edward U. Taylor Elementary School building now holds the Taylor Science Center, where classroom science kits are processed and stored for Montgomery County public schools.

For decades following the Civil War, Montgomery County spent significantly more money on education for white students than for African Americans. African American schools had a significantly shorter academic year, and their funding for textbooks, facilities, and teacher salaries fell far short of what white schools received. Early African American schools were often one-room structures or spaces that churches donated or rented out. In Boyds, African American students first went to a one-room school established in 1878 at St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church, and then to a dedicated one-room schoolhouse built in 1895 (Boyds Negro School, School No. 2, District 11, which is listed on the county’s Master Plan for Historic Preservation).

School No. 2, District 11, also known as Boyds Negro School. Montgomery County Master Plan Site #18/11.

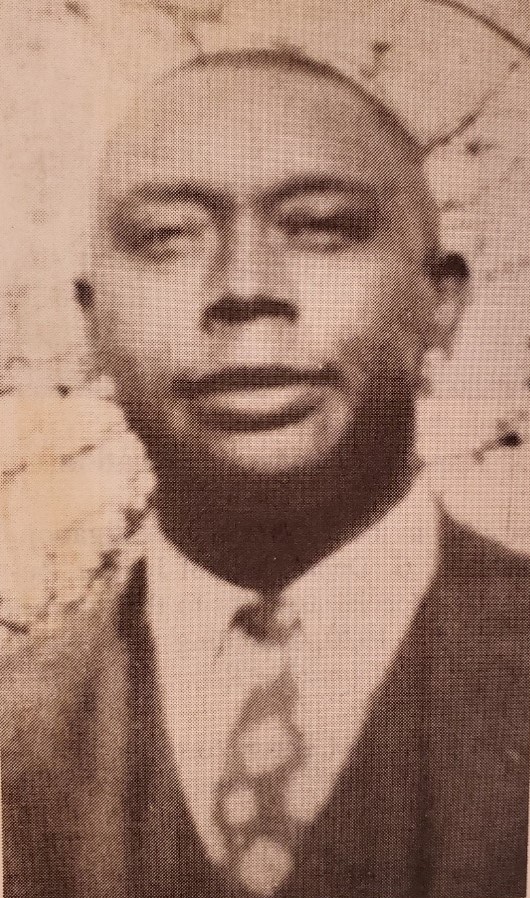

Edward U. Taylor, undated. Source: Montgomery Historical Society, Public School Vertical File.

By the 1940s, the gap between white and African American schools had widened so far that the illusion of “separate but equal” was transparently false. Through a concerted effort to make the “separate” schools more “equal,” individuals like Edward U. Taylor (Supervisor of Montgomery County Colored Schools), and advocacy groups such as parent-teacher organizations and the League of Women Voters convinced Montgomery County Public Schools to dedicate funding to build new African American elementary schools. This included the Edward U. Taylor Elementary School, completed in 1952. These schools met modern school design standards with features such as concrete structural systems with brick veneer, ribbon metal windows providing light and ventilation, and access from each classroom to the exterior. African American communities celebrated these modern buildings as an accomplishment after years of disinvestment.

Just two years after the Taylor School’s completion, the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka found racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional. As a result, Montgomery County Public Schools moved to desegregate. This complex process was made more difficult by efforts to minimize the percentage of African American students at any given school, and by persistent discriminatory real estate practices that had residentially segregated the population. The Edward U. Taylor School was one of the last schools to be desegregated by the county and the only formerly segregated elementary school to remain open as an integrated elementary school.

Historic designation of the Taylor School represents a unique chance to document the evolution of educational facilities and opportunities for African American students over a 100-year span. The proximity of the Taylor School, Boyds Negro School, and the original St. Mark’s Episcopal Church site along a short stretch of White Ground Road in Boyds comprises a cultural landscape that reflects the progression in the educational experience for African Americans from the immediate aftermath of the Civil War through the mid-20th century. Designation of the school would protect the site as a place where residents and visitors can physically experience a racially segregated place from the recent past and reflect on persistent inequalities stemming from decades of public policy that prioritized white residents.

Historic Preservation staff are in the process of evaluating the Taylor School and will make a recommendation to the Historic Preservation Commission and the Planning Board about whether it meets criteria for designation in the Master Plan for Historic Preservation. An important part of this work is collecting the stories of students, teachers, and staff who remember the Taylor School. Do you or your loved ones have memories of learning or working there? We invite you to share these with us so we can more fully tell the Taylor School’s unique story.

Keep an eye on the Historic Preservation Office website for updates as this project moves forward.