View of the façade of the Romeo and Elsie Horad House looking south from University Boulevard West, 2022. Source: Montgomery Planning

As you travel east on University Boulevard from downtown Wheaton, past the commercial strips and gas stations, you’ll encounter a Georgian Revival brick house with imposing chimneys. This simple but elegant home, with its symmetrical design and matching bay windows, stands in stark contrast to the modernist Art Deco WSJV Transmitter across the street and the post-WWII Ranch and Split-Level houses scattered throughout the nearby neighborhoods. The historic house was the home of Romeo and Elsie Horad. Built on Elsie’s ancestral land, the house stands as a testament to the achievements of the Websters, Sewells, and Horads who worked tirelessly to improve conditions for African American residents throughout Montgomery County and Washington, DC.

The Montgomery County Historic Preservation Commission recently recommended that the house built in 1938 be designated for historic preservation as part of Montgomery Planning’s University Boulevard Corridor Plan. The Planning Board is expected to consider that recommendation in 2025, and the County Council would have final approval on designation.

A hub for Black community activism

This area has been home to members of the Horad, Sewell, and Webster families since 1894, when Jane and Charles Webster bought nearby property and built an earlier home in Wheaton’s growing Black community. The Websters advocated for Black residents to become involved in politics in a time when they had no representation in government. The Washington Times listed Charles Webster as a speaker for a 1904 rally of the “Negro Republicans of Wheaton” in support of then-President Theodore Roosevelt’s bid for reelection. In 1906, Charles joined other Black activists in rallying support for the candidacy of local developer Brainard Warner for Congress.

The Websters’ fourth child, Martha, and her husband, Edward Sewell, bought property nearby and transferred part of it to their daughter and son-in-law, Elsie and Romeo Horad.

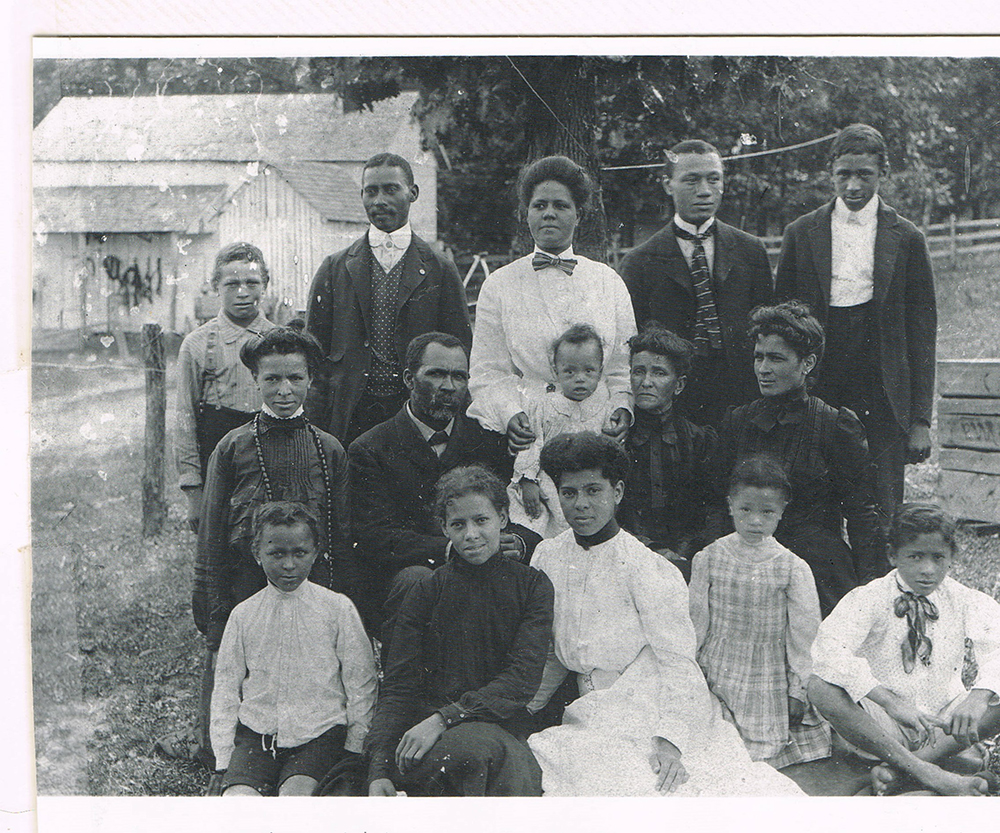

Portrait of the Webster family, with Charles sitting second from left in the middle row, and Jane sitting second from the right in the middle row, date unknown. Source: Papers of Sewell Horad, Montgomery Planning

The Horads were proud of the Colonial Revival house they built on the lot gifted to them, believing it showed the standard of living that Black residents could reach, if given the opportunity. The house became a hub for their community work as they continued their family legacy of participating in local and state politics.

Elsie and Romeo Horad had both graduated in 1916 from M Street High, then one of Washington, DC’s most prestigious schools for Black students. Immediately after marrying, Romeo joined the Army and was deployed to France, possibly as a court reporter. After the war, he and Elsie lived in DC, where he was a typist for the Navy. Elsie enrolled in the Minor Normal School teacher’s college and raised their children while Romeo attended Western Case University in Ohio. She was quickly hired into the DC public school system, where she taught for 37 years. Her youngest brother, Bernard Sewell, also taught in the public school system, and her middle brother, Webster Sewell, played a critical role in the health and welfare of the local Black community as a doctor in Wheaton and later in Norbeck.

After returning from Ohio in 1923, Romeo earned a law degree from Howard University and later was recognized for modernizing the DC land record system. In the late 1920s, Romeo and Elsie joined the Montgomery County Colored Republicans and rose to leadership roles. In 1939, Romeo established R.W. Horad Realty Inc. at a time when segregation, particularly racially restrictive land covenants, limited opportunities for Black homeownership. Montgomery County residents wouldn’t elect their first Black countywide representative until the 1970s, but Romeo repeatedly demonstrated the viability of Black political candidates, as he ran for delegate to the Maryland State Republican Convention twice and for the 5th District representative to the Montgomery County Council.

Fighting for equal rights

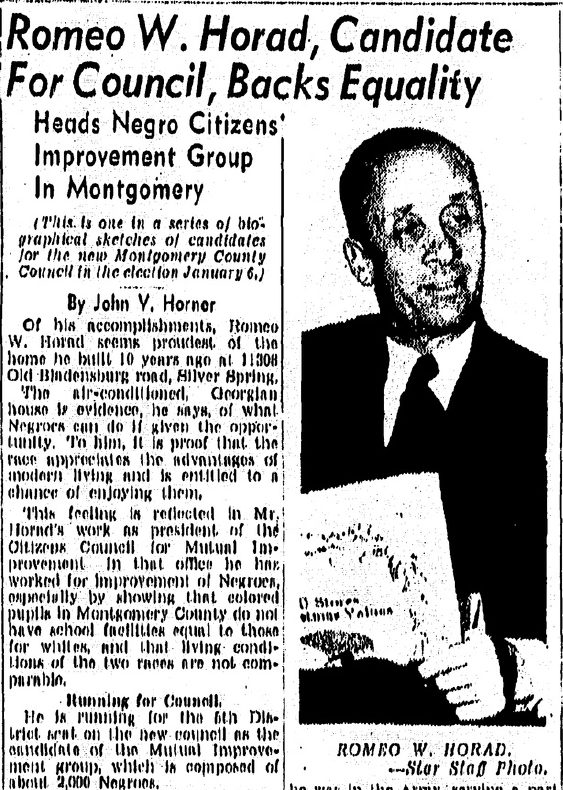

“Romeo W. Horad, Candidate for Council, Backs Equality”, December 27, 1948, p.13. Source: Evening Star

Romeo’s groundbreaking political candidacy, platform of equity, and strong support from the Black community received coverage both in local newspapers and those as far afield as the Alabama Tribune and Pittsburgh Courier. He also lobbied for Black political power and engagement, working with the State Allied Republican Club to register 100,000 Black Maryland residents to vote.

In 1944, Romeo testified before a United States Senate subcommittee about the slum-like conditions in areas of DC where Black residents were allowed to live. Locally, he led the Montgomery County Citizen’s Council for Mutual Improvement, demanding that the county provide better living conditions for people of color, including by adding Black police officers, improving roads and utility services, and removing ‘Jim Crow’ signs from the courthouse.

Romeo partnered with White real estate brokers Raphael and Joseph Urciolo to buy DC houses with covenants that prohibited Black buyers. They would then resell the properties to Black buyers, sparking a series of court cases challenging the legality of such racially restrictive covenants. Romeo’s challenges paved the way for Hurd v. Hodge, the 1948 DC companion case to Shelley v. Kraemer, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that found enforcing racially restrictive covenants to be unconstitutional.

The Horad home, now owned by the adjacent Iglesia Cristiana Canaán Church, is a tangible connection to the legacy of the African American community in Wheaton and Maryland. It stands as a symbol of their family legacy, reminding us of the fight for civil rights, their pursuit of equal opportunities, and their profound impact on shaping our community. As we celebrate Black History Month, it is crucial to share and preserve the legacy of this house and the stories of those who lived here.

About the author

Serena Bolliger is a cultural resource specialist in Montgomery Planning’s Historic Preservation Office with expertise in hands-on restoration, energy-efficient historic preservation, and researching holes in the historic record. Serena has master’s degrees in museum studies, historic preservation, and urban planning. Prior to joining Montgomery Planning, she worked with historic and cultural resources for Arlington County, Virginia.

D A

This is amazing! My husband grew up attending many events in this house as his best friend’s grandmother was a Horad. I had no idea of the vastness of this family’s legacy in our community.