Learning to read the landscape

Montgomery Planning is exploring the relationship between burial grounds and surrounding landscapes to better understand these sites and find graveyards whose locations have been lost. Cemeteries are important because they are valued by descendants and may hold valuable information about people’s lives historians and genealogists cannot find anywhere else. Since 2017, county law has required Planning staff to keep an inventory of all the graveyards in the county.

Some burial sites in Montgomery County dating to the 1700s and 1800s are no longer visible, and their exact locations have been lost to time. This may be because the graves were never marked, or the markers have been moved or have deteriorated away. Other sites may be hard to recognize. It is common for graves in Montgomery County to be marked with a fieldstone, a large rock unmodified in any way, and may not be obvious to a casual observer. This is often true for the burial sites of people who were held in slavery. Prior to Emancipation, over 30% of Montgomery County’s people were held in slavery; we believe that many of their burial places remain unknown. As we plan future development in the county, it’s important for us to identify the locations of these sensitive resources to avoid unintentionally destroying them.

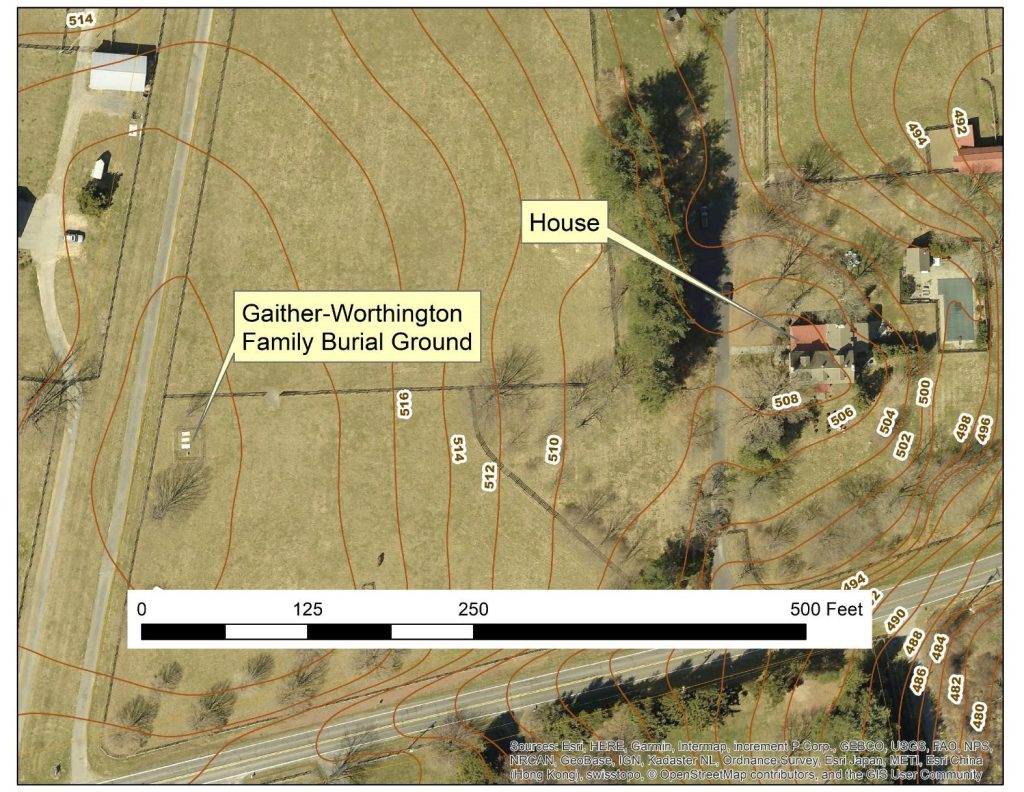

An example where we know for certain the location of both the family house and cemetery. The Gaither-Worthington Family Burial Ground is about 450 feet from the historic house on a low hill east of Laytonsville.

There are 55 family cemeteries in the Montgomery County Burial Sites Inventory whose locations we know for certain because they still have visible markers and where we know the location of the original family house as well. Examining maps of places like the Gaither-Worthington Family Burial Ground, I found that most of these cemeteries are between 250 and 500 feet from the original family home. However, the distance varies a lot—from only 50 to over 1000 feet. I also learned that most family cemeteries are sited on a locally prominent landform such as a small hill or the edge of a terrace such as the Clipper Family Cemetery. When I compared the elevation of each cemetery site to the average elevation around them within 500 feet, I found that most were on higher ground than their surroundings.

The Clipper family cemetery is an example of a cemetery located on a river terrace. It is located above the Potomac River, west of Seneca Creek.

Understanding these relationships between cemeteries and their landscape settings offers us a way to find graveyards whose exact locations have been lost or forgotten

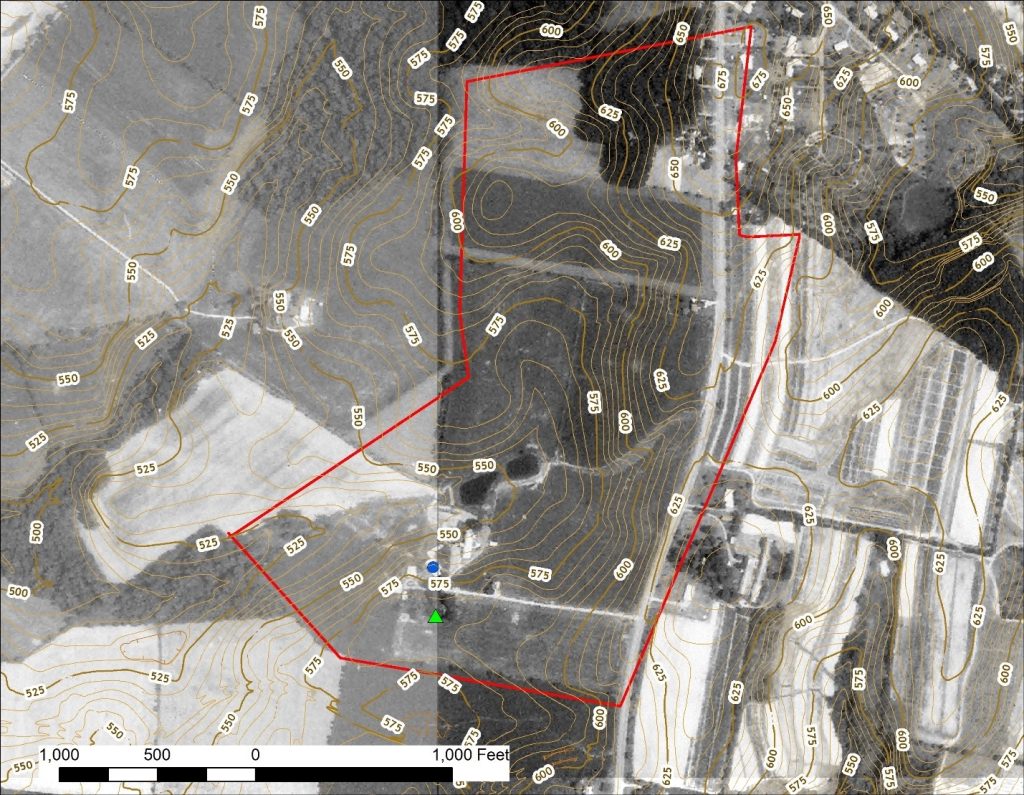

The Charles Purdum Family Cemetery

Let’s take the Purdum family burial ground as an example. When Charles Riggs Purdum died in 1864, he was buried on the farm he had purchased in 1837 near Clarksburg. Four years later, his widow Margaret Purdum sold the farm after she remarried. The 1868 deed excludes a quarter of an acre from the sale “for the family graveyard” but doesn’t say where on the property it was. I was able to map the boundary of the farm and original house location in 1868. I then looked at the topography and aerial photographs from 1951 and 1979 when the property was still a farm and identified a group of trees about 250 feet south and about 10 or 15 feet uphill from the family home. We don’t have a record of who was buried in the lot other than possibly Charles Riggs Purdum and his son George. Assuming they were originally buried on the farm, at some point their graves were moved to Upper Seneca Baptist Church Cemetery. However, Charles Purdum held at least six people in slavery as of 1860. Since people held in slavery were sometimes buried near the graves of their enslavers, it is possible that people the Purdums enslaved could have been buried nearby. If marked Purdum family graves were moved prior to the property being redeveloped, any graves of those they enslaved might still be near the original location. We will be bringing this location to the Montgomery County Planning Board for the formal addition to the Burial Sites Inventory later this spring. The likeliest location is now within a road right-of-way or adjacent private property, making further investigation in this location a challenge. However, if in the future there are proposed changes to that roadway, there may be an opportunity for archaeologists to investigate the site.

Possible location of the Charles Purdum Family Cemetery (green triangle) south of and slightly uphill from the family home (blue dot), southeast of Clarksburg.

The Conway-Jackson Cemetery

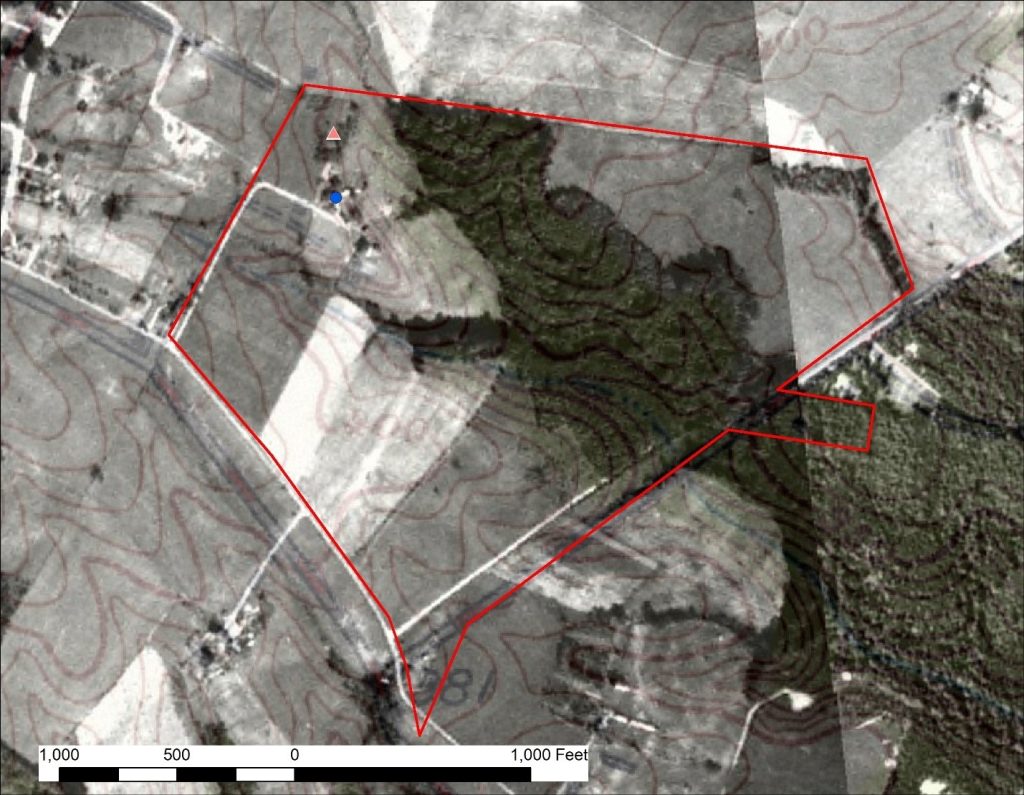

I used the same process to help identify the probable location of an African American burial ground in the Fairland area. A history of Burtonsville published in 1976 by Audrey Lord describes a cemetery once on the property of Randy Roby purportedly in the pathway for the realignment of US 29. Her informant, Roy Miles, remembered between 100 and 150 stone markers he believed were associated with people once held in slavery, including “Grif Conway and Emma Jackson.”

Emma Jackson was the daughter of Malinda Jackson who purchased the cabin where she and her family had been enslaved from her former enslaver Ann Downs in 1869. Griffin Conway was a boarder who lived with the Jacksons on their property. Both the Jackson homestead and the Conway-Jackson cemetery site are located on land that once belonged to Downs. The nearby farmstead corresponds to where real estate maps indicate Downs and later owners had their homes. There are Jackson descendants living in the area today.

To find their graves, I mapped the boundaries of the Roby farm onto an aerial photograph taken a few years before Columbia Pike was moved. That photograph and engineering plans prepared by the Maryland Department of Transportation State Highway Administration shows the farmstead and an orchard about 250 feet north of the house along a terrace edge now in the right-of-way for the highway. We don’t have any information yet about what happened to the graves, but Miles told Lord that descendants were not found at the time the highway was built in 1955, and that the cemetery was destroyed. This cemetery is probably within a Maryland State Highway right-of-way, so as with the Purdum cemetery, field investigation by archaeologists is a challenge unless there is a major project to change the road. Hopefully, further research into Maryland State Highway files and conversations with community members and descendants may find clues about what happened to the graves.

Possible location of the Conway-Jackson Cemetery in the Fairland area shown on a 1951 aerial photograph with contemporary topographic lines.

Now that we’ve identified these possible grave sites, what’s next?

Our next steps for these and sites like them is to continue with research in historical archives. That includes deeds, wills, maps, and aerial photographs. Where we have the opportunity, we can then follow up with limited archaeological investigations using techniques that don’t involve digging like ground penetrating radar (GPR). GPR has been used successfully to find unmarked historical cemeteries. GPR instruments transmit radar waves into the ground and records how they reflect off material under the ground. There have also been some encouraging results from studies using human remains detection dogs to find lost burial sites. We hope that by drawing on such diverse methods with patience and persistence we may be able to recover lost or forgotten parts of our historical landscape.

About the author

About the author

Glenn Wallace

Incredible, Brian! If you need an assistant out there, let me know!

ruth katz

Brian this is so cool. You’re such a good writer…it’s understandable by this non archeologist! Now u have me wondering about the teeny little graveyard a few doors down from our house. I need to check the registry link you provide. Where’s the house and who lived in it? I’m also surprised that 30% of Montgomery county’s people were slaves. On this land bad things happened and it wasn’t all that long ago. Thank you for doing this important work.