Sustainable Growth is not an Oxymoron

By Casey Anderson and Steve Findley

Thrive Montgomery 2050 builds on the ideas laid out in the Wedges and Corridors plan to reinforce anti-sprawl policies and incorporate new insights about sustainability and development. This post explains the environmental benefits of the compact growth footprint established by the Wedges and Corridors plan and updated by Thrive Montgomery 2050 – and why any alternative path would chew up more land, cut down more trees, and undercut efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the impact of climate change.

Reaffirming and updating the Wedges and Corridors commitment to compact form

The Wedges and Corridors plan laid the groundwork – no pun intended – to preserve land for resource conservation and agriculture. The Agricultural Reserve, strong stormwater and forest conservation measures, and the compact growth footprint that gave the plan its name are all products of the Wedges and Corridors plan and subsequent refinements.

Take a look at this pie chart showing the various categories of land protected from development:

A land conservation success story

As the chart shows, the Wedges and Corridors plan and related policies have placed more than half the county’s land area off limits to almost any kind of development. Local, state and national parks combined with the Agricultural Reserve cover about 44 percent of the county’s land area. Forest and agricultural easements outside of parks and the Ag Reserve, together with stream buffers and other environmental restrictions, bring the total to about 53 percent. Most of the remaining land in the county is used for public purposes, such as roads and schools, or has already been developed for private uses such as housing, retail, or offices.

The result has been not only to limit the impact of development but by some measures to improve environmental performance. For example, forest cover increased from 25.5% of the county’s land area in 1951 to 29.3% in 2015, while our population grew from 165,000 to more than one million. The Wedges and Corridors framework has been a big reason for this success.

Thrive Montgomery updates these approaches to integrate state-of-the-practice thinking about how to make other aspects of land use planning reinforce the benefits of compact growth, but it recommits the county to the basic Wedges and Corridors footprint – because it has worked.

The alternative to Thrive Montgomery 2050 is not less growth – it’s more sprawl

Thrive calls for making plans to accommodate about 200,000 more people over the next thirty years, not because the Planning Board or Department think this is a good or bad number of people to add to the county but because demographic and econometric forecasts estimate that our population will grow by roughly this number of people with or without Thrive.

If population growth is inevitable, then the question is not how many residents we need to accommodate but where to put them. There are some who believe that more intensive redevelopment and infill will result in fewer trees and more environmental degradation, but this argument has it exactly backwards. If we can’t build a moat around the county to keep new residents out, then the only alternative to more focused growth is sprawl, and sprawl means we lose more trees and mature forest.

How compact form, transit, and Complete Communities work together to create sustainable land use

This chart compares the environmental impact of different development patterns: (1) the least compact kind of sprawl, (2) a more compact footprint and (3) the most compact form, usually associated with large cities:

Comparing neighborhoods

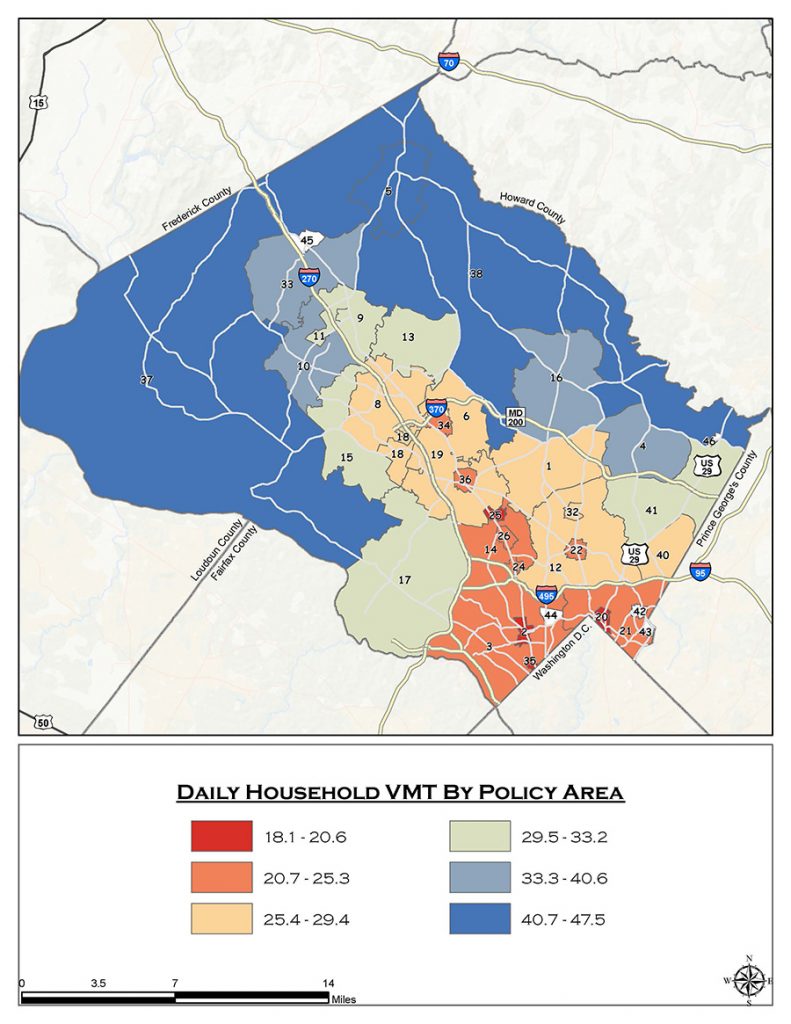

While many people think of transit as the sine qua non of sustainable development, this chart shows that the starting point for improving the environmental performance of the built environment is compact form – that is, keeping our growth footprint from spreading outward. While Thrive Montgomery 2050 urges a reorientation of public and private investment around walkable, bikeable, transit-oriented development, it also recognizes that focused growth reduces driving even in places not served by high quality transit. The map below illustrates the point:

Source: Montgomery County Planning Department’s Travel 4 Transportation Demand Model, 2010

As you can see, households with the lowest vehicle miles travelled (VMT) are located in areas closest to Metrorail stations. These areas, shown in dark red, are within walking distance to high-quality transit service. Not surprisingly, people who live in these areas tend to drive less than people farther from transit.

The role of Complete Communities

But what about the orange areas inside the Beltway and up the I-270 corridor? Households in these neighborhoods generate relatively low VMT, even though they are not in a central business district or located next to a Metro station. People who live in these areas are not within walking distance of Metrorail and most are unlikely to feel that they can give up their cars – but most daily needs are just a short drive away. As a result, people in these areas, shown in orange, drive more than people who live within walking distance of Metrorail but far less than people who live farther away from major centers of activity.

The least intensively developed parts of the county, shown in blue and green, generate much higher VMT per household because their residents not only need to drive, they need to drive long distances to get to work, to school, or even to pick up groceries. Transit-oriented development is the best kind of development from the point of view of curbing tailpipe emissions, but compact development without transit is much better than sprawl. This is a key reason for encouraging infill and redevelopment in places such as Westbard, which is not immediately adjacent to Metrorail but is close enough to downtown Bethesda, Friendship Heights, and the District of Columbia to limit the need for residents to drive long distances.

Walkability, and a mix of uses: the building blocks on the foundation of compact form

Thrive Montgomery 2050 recognizes that the basic elements of urbanism – a compact form of development; a mix of uses, building types, and lot sizes; and design and infrastructure to support walking, biking, and transit both directly and indirectly – work together to optimize environmental outcomes, including better water quality and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

This chart shows why the most important step local government can take to protect the environment is to focus development in compact “complete communities” with sufficient densities to support a variety of housing types, retail and office space, parks and public spaces, all preferably within walking distance:

Comparing households

As the chart shows, dense mixed-use communities reinforce the environmental advantages of compact form. That’s because the choice of development patterns and the typology of buildings have an outsized impact on per capita energy consumption. The data shows that a large single-family home in a subdivision with three cars would use close to 400 million BTUs per year. The same home with energy conservation features and efficient cars would use 270 million BTUs. In contrast, a townhouse in a mixed-use neighborhood with convenient transit and only two cars would need 245 million BTUs, less than the “green suburban” home. If that same townhome used solar panels, energy conservation measures, and fuel-efficient cars, it would use just 167 million BTUs – a threefold savings. A green condominium in an urban center would perform on average 75 percent better than the suburban home located in auto-oriented sprawl.

In moving away from sprawl to a more compact development pattern, annual carbon emissions, land consumption, and VMT per household all decline while measures of walkability increase. There’s a role for direct environmental regulation such as green building requirements and stormwater management rules, but the most important factors determining sustainability are density, the diversity of uses, and accessibility via walking, biking and (ideally) transit.

From Wedges and Corridors to a web of corridors

Thrive Montgomery 2050 proposes to recognize that the Route 29/I-95 corridor, included in the original Wedges and Corridors scheme but written out in 1993, and the Georgia Avenue corridor, excluded from the 1964 plan before the Red Line was built, are both appropriate places for more development. Thrive also endorses the principle that some types of growth in centers of activity such as Damascus, Poolesville and Sandy Spring should be allowed even though these areas are outside of the main growth footprint. As long as development is confined to parts of these communities already built out in previous eras, additional growth can avoid causing sprawl.

Compact, Complete Communities are a proven formula to achieve environmental resilience

The land use recommendations in Thrive Montgomery 2050 mirror the recommendations of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for creating healthy, sustainable communities.[1] These recommendations are the foundation for achieving the environmental goals of Montgomery County for reducing climate change impacts, preserving water and air quality, protecting biological diversity, and creating healthy places for people. Implemented through policy guidance, incentives, and judicious regulations, Thrive is our way forward to a sustainable, resilient future. In our next post, we will look at how environmental resilience is woven throughout Thrive Montgomery 2050.

[1] Our Natural and Built Environments: A Technical Review of the Interactions Among Land Use, Transportation, and Environmental Quality, Second Edition. United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Sustainable Communities, Smart Growth Program, 2013.

About the authors

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

Steve Findley has held various positions with the Montgomery County Department of Parks and Montgomery County Planning Department for over 31 years. He began work with the Parks Department as a Natural Resources Specialist in 1990, moved to the Environmental Planning Division of the Planning Department in 1995, went back to Parks to become a Nature Center Director in 2000, and returned to Planning in 2008, where he now works as a Planner IV with the Midcounty Planning Division focusing primarily on environmental planning issues. Currently, he works on sustainability recommendations for Master Plans including modeling greenhouse gas emissions, and reviews developments for compliance with the Forest Conservation Law and other environmental policies and regulations. In 2020, he became a Certified Climate Change Professional, a credential granted jointly by the Association of Climate Change Officers and the State of Maryland.

Robert Smythe

This explanation sounds reasonable and sensible. I can only hope that the County sticks to the intentions expressed in it. As a County resident and homeowner for nearly 50 years I have seen too many cases where developers take the zoning and building limitations as a point to begin negotiating for more exceptions or waivers or “deals” such as allegedly “affordable “ housing units to create more land-gobbling sprawl development.

And don’t overlook the fact if residents in the relatively dense areas can’t get enough park and public open spaces or decent, affordable public transportation or find their neighborhoods choked with vehicular traffic, we will start looking to move out of the “dense” areas to places that offer more space and other amenities. This was the norm until recently. How did Marriott get away with provider almost no public green space, and what if anything have they done to relieve the inevitable increase in traffic that their new downtown Bethesda development will create? Why are the sidewalks in front of their buildings almost entirely brick, with a few token trees in small holes? Why isn’t EVERY new commercial building in Montgomery County REQUIRED to have green roofs and/or large solar arrays? These are companies that can easily afford to do these things that will actually benefit them as well as the public. Get tougher!!

Robert Oshel

Obviously the data in the Comparing Neighborhoods and Comparing Households tables is correct. People living in condos with one car would use less energy than people living in single family homes with three cars. Duh! This whole analysis is over-simplistic.

How many people prefer in the long run to live in dense condos rather than single family homes with green space to raise their families? It seems to me the goal of Thrive and the Attainable Housing Strategies Initiative, etc., shouldn’t be to try to increase density everywhere (except the real sprawl R-200 zone — why is that?). The goal of Thrive, etc., ought to be to best serve how the people of Montgomery County want to live. Given the the intense public reaction to Thrive, I don’t think that is dense urban living.