Today the Planning Board finalized its draft of “Thrive Montgomery 2050,” a proposed framework for the physical development of the county over the next three decades. Thrive Montgomery is the first complete overhaul of our community’s comprehensive plan since 1964, so it represents a chance to reconsider fundamental assumptions not simply about the regulation of development but about the nature of planning and what its objectives should be.

This series of posts will outline Thrive Montgomery’s recommendations for the future of land use, transportation and public amenities such as parks, but first I will explain what our proposal is trying – and not trying – to do. Thrive Montgomery is about how ideas that have proven successful in building communities in the past can be applied to improve economic performance, racial and socioeconomic equity, and environmental sustainability in the decades ahead.

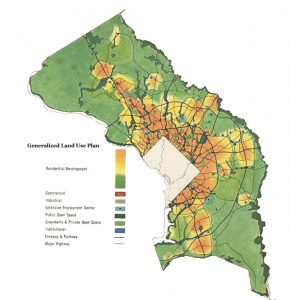

These goals are very different from the ones identified in the “Wedges and Corridors” plan adopted by the county in 1964 and in effect ever since with only minor modifications. You will not find the phrase “racial equity” in that document, even though Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech before 250,000 people at the March on Washington while the Wedges and Corridors plan was being debated. And even though Rachel Carson, whose 1962 book, “Silent Spring” launched the environmental movement, was a resident of Silver Spring, the Wedges and Corridors Plan did not address issues such as stormwater management, much less the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. For that matter, the Wedges and Corridors plan includes little discussion about how land use might influence the county’s economic prospects.

None of this is to say that the Wedges and Corridors plan was a failure. In fact, in many ways it was exceptionally forward-thinking for its time. For example, it anticipated the need to reduce reliance on automobiles and build transit networks while emphasizing the conservation of land to prevent sprawl and preserve space for recreation and farming. In later posts I will discuss how decisions about the regulation of real estate development; construction of public infrastructure; and management of parks and public spaces helped Montgomery County become one of the most desirable places to live in the United States yet failed to produce the conditions for broadly shared and sustainable prosperity or to fully prepare us for the challenges of the future.

Thrive Montgomery represents an attempt to correct for these shortcomings, but it does not try to address or even anticipate every challenge and opportunity Montgomery County might face over the next thirty years. Our approach is rooted in the idea that planning is most likely to generate useful recommendations when it applies the lessons of the past than when it attempts to predict the future. If you’re looking for a discussion of the implications of autonomous vehicles for transportation or how robots will influence the workplace, you will be disappointed.

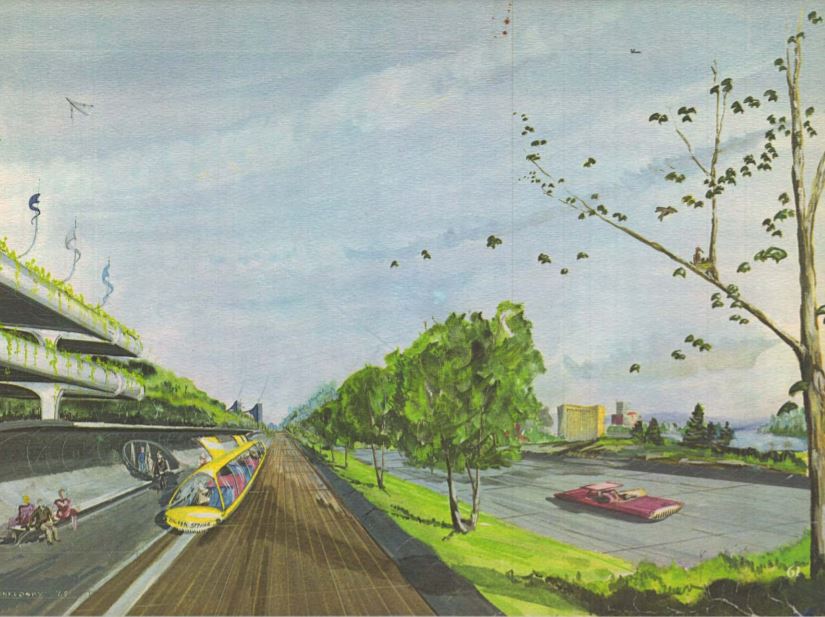

How can we plan if we don’t try to anticipate the events and trends that might affect us? The short answer is that making sweeping predictions about the future is a fool’s errand. When planners attempt to be futurists the results range from the merely embarrassing (the Wedges and Corridors plan said it was “too early to predict the role that may be played by helicopters or other means of air transportation within urban areas but the possibility of a substantial role must be kept in mind”) to the destructive (as with the attempts by 20th century planners to reshape the world around automobiles led cities to raze entire neighborhoods to make room for freeways).

Of course, we have to make some educated guesses about the future. We should be thinking about how climate change, pandemics, or terrorist attacks might affect us, and we need to assess the implications of autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, and economic change. Still, when plans lean too heavily on assumptions about future trends, events, and forces they are unlikely to be useful for very long. The purpose of planning is not to predict and respond to a single future but to be prepared to face multiple, unpredictable futures. Thrive Montgomery, like other long-range plans, has to be sufficiently detailed and specific to provide meaningful guidance for action but sufficiently broad and flexible to remain relevant in the face of unforeseen changes.

This is a difficult balance, but the good news is that the foundational elements of what make places work for people have proven remarkably consistent over time. The plan relies on those foundations to establish a framework for the next generation of our county’s development. The posts that follow will cover these basic concepts and how they apply to land use regulation at the scale of the region or county, neighborhood or district, and individual parcel or project as well as to functional objects of planning such as housing, transportation, and recreation. I’ll show how these pieces fit together to create the conditions for a more prosperous, equitable and sustainable future while building community and helping all our residents live happier, healthier lives.

About the author

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

clara m lovett

Look forward to reading your blogs. I get the distinction between preparing for the future and predicting the future. I’d like to hear (read?) more about what you consider “foundational elements” that make places work for people