Thrive Montgomery includes dozens of recommendations touching on land use, transportation and many more topics. In the following posts I will describe what I see as the most interesting and important concepts in the plan, but first I want to outline the general approach that informs this plan’s specific proposals – an approach that can be summarized as “urbanism.”

The plan applies the principles of urbanism – a term used as shorthand for a set of ideas about what makes human settlements successful – to frame recommendations about the location, form, and design of development; policies on transportation and housing; and the kinds of parks, recreational facilities, and public spaces we need in the future.

What we mean by “urbanism”

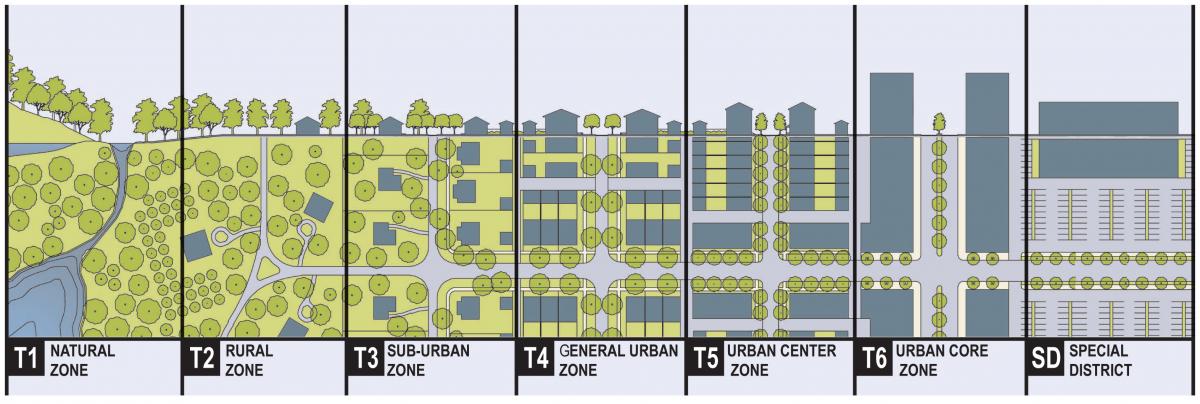

The idea of the “transect” is central to the recommendations in Thrive Montgomery 2050. From the College of New Urbanism Public Square Journal: “The rural-to-urban transect is a system that places all of the elements of the built environment in useful order, from most rural to most urban. For example, a street is more urban than a road, a curb more urban than a swale, a brick wall more urban than a wooden one, and greater density is more urban than less density. If all of the built elements are in sync, the place can be described as “immersive.” The elements are symbiotic. Naturalists use the transect concept to describe the characteristics of ecosystems and the transition from one ecosystem to another. Andres Duany (principal of DPZ Partners) and other urbanists applied this concept to human settlements, and since about 2000 this idea has permeated the thinking of new urbanists. The rural-to-urban transect is divided into six zones: natural (T1), rural (T2), sub-urban (T3), general urban (T4), center (T5), and core (T6). The remaining category, Special District, applies to parts of the built environmental with specialty uses that do not fit into neighborhoods.” Image courtesy DPZ CoDesign.

If you Google the term, you will find different definitions of urbanism along with permutations including New Urbanism, walkable urbanism, landscape urbanism, market urbanism, and more. Thrive Montgomery defines urbanism as an approach to planning that emphasizes (1) a compact form of development; (2) diverse uses and building types; and (3) transportation networks that take advantage of and complement these two land use strategies, at all densities and scales.

Park Potomac, located adjacent to an interchange on I-270 south of Rockville, illustrates how the principles of urbanism can be applied in suburban settings. Park Potomac incorporates the urbanist ideas of walkability, a mix of uses and focused activity in a tightly defined location. These features can create great places that support a high quality of life outside of cities and without access to transit.

This approach calls for focusing growth in a limited number of locations, avoiding “sprawl.” It encourages the agglomeration of different uses such as retail, housing, and offices as well as diversity within each type of use. For example, a variety of housing sizes and types near retailers and offices helps to ensure that people of diverse incomes can live and work near each other, creating more racially and socioeconomically integrated neighborhoods and schools. It also emphasizes the importance of walking, biking and transit and reduced reliance on cars.

New Carrollton in Prince George’s County is an attempt at transit-oriented development that fails to effectively integrate the elements of high-quality urbanism. Development around the station is intensive but neglects the orientation of buildings to the public realm; lacks safe and attractive pedestrian connections, and does not create a sense of place. Photo by Christopher Sayan CC BY-SA 3.0

The dismal conditions for walking in and around Tysons Corner have been cited as one of the reasons Silver Line ridership has been lower than expected. Tysons Corner may become more walkable as new development projects take shape, but for now it shows why transit-plus-development does not always equal transit-oriented development (TOD). Photo by Joel D. Gray CC BY-SA 4.0.

Of course, other factors – particularly quality and thoughtfulness in the design of buildings, streets, neighborhoods, parks, and public spaces – are also important. Combined with the fundamentals of urbanism, design excellence can help create a sense of place, facilitate social interaction, and encourage active and healthy lifestyles.

It’s not just for cities

The principles of urbanism are equally relevant to rural, suburban and urban areas. In fact, the preservation of land for agriculture in a place like Montgomery County depends on concentrating development in urban centers instead of permitting sprawl, and even suburban and rural areas benefit from a mix of uses and housing types at appropriately calibrated intensity and scale. With attention to the functional and aesthetic aspects of design, urbanism is not only consistent with a commitment to maintaining the best of what has made our county attractive in the past but is necessary to preserve and build on these qualities while correcting the errors of auto-centric planning and the damage it has done to the environment, racial equity, and social cohesion.

In subsequent posts I will discuss some of the most significant concepts in Thrive Montgomery and show how they represent an integrated set of ideas – rooted in the principles of urbanism – that orient the tools available to planners around improving economic performance, racial justice, and environmental sustainability while strengthening the health of our community.

About the author

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

Bob Cissel

Casey

I applaud your efforts in giving brief but detailed descriptions of the concepts on Thrive 2050. The general public needs to understand the why and the how this plan can change the face of our county. I’m sure there will be issues from all the work groups around the county. And rightfully so they should have a voice. But we need to address our short comings from the planning of the 1980-2000 so we can create a positive environment for future generations. We’re giving our students a great education, sending them off to college and they don’t return because frankly there are better places to live that have more affordable housing, better transportation systems which then attracts better job opportunities. There’s a reason the tech companies are stacked up in the Bay area and Seattle. Their city planners were ahead of their time back in the 1970-80’s. It won’t be easy and of course you know how hard I work to protect the AG Reserve for our future generations of farmers. But there should be something for everybody when it comes to city planning. But we will have our work cut out for us over the next 5-10 years.

Lisa Cline

MoCo’s attempts at Urbanism, in my layperson’s opinion, have largely failed due to the diminished value placed on walkability and natural elements. I will cite Downtown Crown and Pike & Rose as two examples. To walk from store to store, you have to negotiate active parking lots and circuitous traffic patterns. The lack of trees is profound. I find most of our suburban Urban developments to be transactional rather than pleasant and inviting. These two examples (and I’ll add Park Potomac into this mix) are like walking behind the scrim in the Truman Show or crossing a moat to get in and out. The new-ish condo in the Tech Corridor on Rte. 28 (Mallory) are like Perdue chicken coops and are feet from the street. Even the juvenile detention center down the street has a more pleasant (by far) surroundings. So I question Density as a goal but would like to learn more about it, so am appreciative of this blog series. Thank you.