A new trend was the design of concrete buildings which expressed the natural character of this building material. Starting in the 1960s, Montgomery County business districts were punctuated by statement buildings that celebrate the raw nature of concrete. The design of monumental buildings constructed with unfinished concrete cladding were influenced by the work of pioneering modernist Le Corbusier and his use of béton brut, or raw concrete. The name was anglicized as Brutalism, a term which has acquired negative connotations. More recently, the style has been dubbed Heroic architecture, as more people have come to appreciate these buildings for their honest expression and as a product of their time.

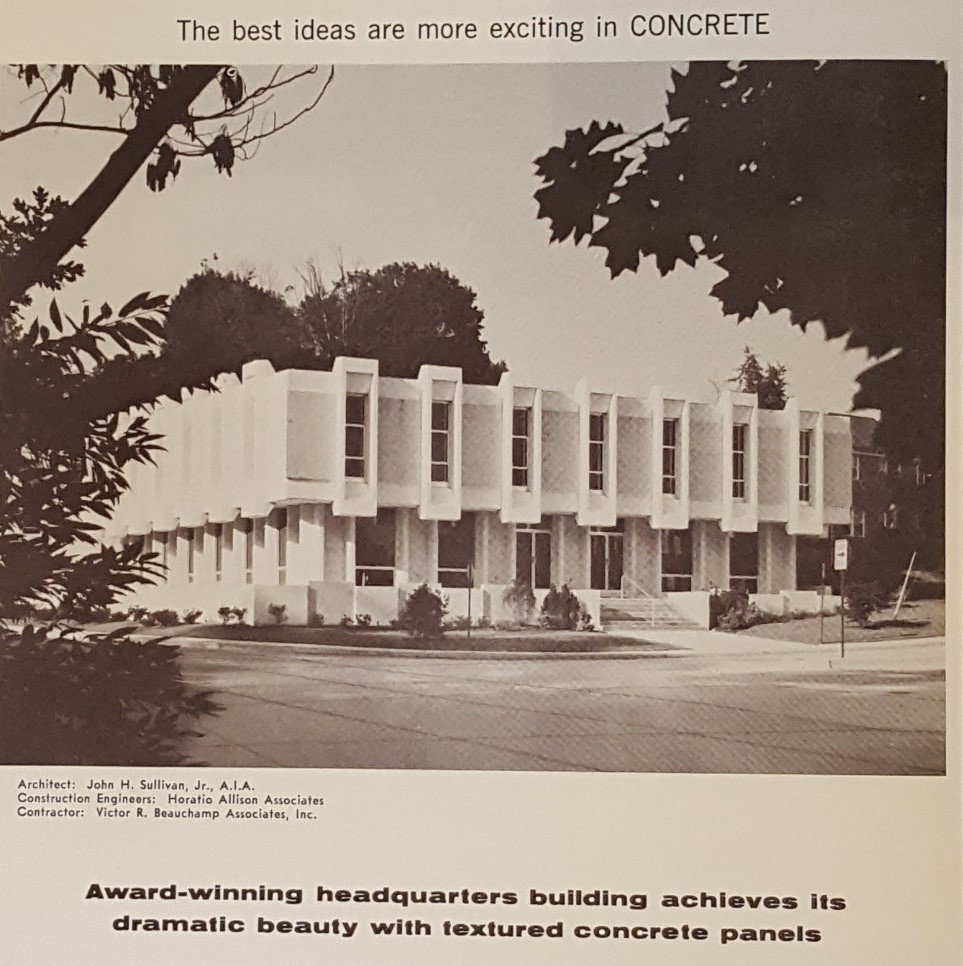

An early local example of Brutalism was the award-winning National Sand & Gravel and Ready Mixed Concrete Associations Headquarters, designed by architect John H. Sullivan.

Potomac Valley Architect, Dec 1964

The NSGRMCA project received a design award from the American Institute of Architects Potomac Valley chapter. How fitting that the national concrete organization chose a showcase of concrete finishes for their headquarters building. Located at 900 Spring Street in downtown Silver Spring, the building retains its original use, now home of National Readymix Concrete Association.

Photo: Clare Lise Kelly 4-2013

Smooth concrete walls exhibit the natural state of raw concrete, while aggregate panels add texture with a pebbled finish. (The panels are attributed to Earley Studios, company of John J. Earley, pioneer in exposed aggregate panels, featured in this previous post.)

Concrete buildings from the mid-century era typically show streaking and staining which are characteristic of the material as it ages. This natural weathering may contribute to a building’s character. As concrete is increasingly accepted as an architectural material, there is hope that the look of natural aging will also gain acceptance.

We have begun to see examples of the application of paint to raw concrete. This practice irreversibly changes—and masks–the natural character of the material.

Just up the street from NSGRMCA is the Montgomery Center, 8630 Fenton Street, designed by Bucher-Meyer. Completed in 1970, the complex included a 14-story office tower with movie theater, underground parking, street-level bank and retail. The Corbusier-influenced project is raised on pilotis and features an entry garden plaza.

The building was in the process of being painted when I took these photographs, a process which has changed its character.

Photos by Clare Lise Kelly 10-31-16

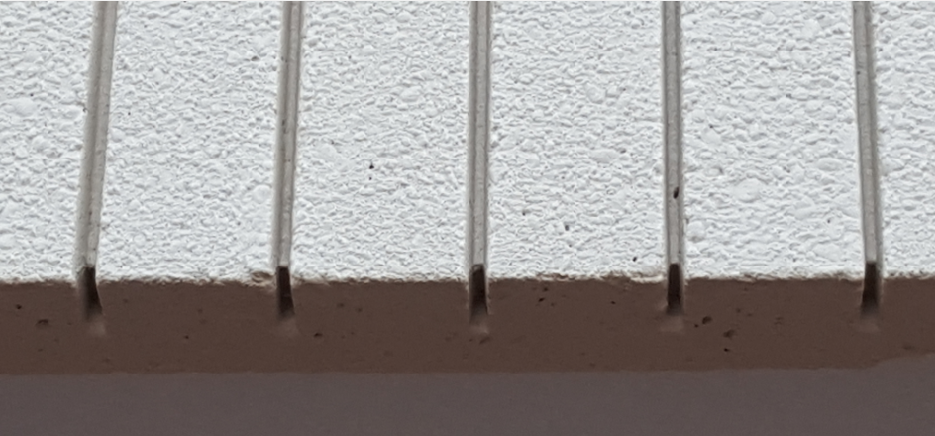

At right is the original concrete surface, showing its natural appearance and texture. The left side has been painted, obscuring visual characteristics of the building’s concrete skin and diminishing the original design intent.

Here is a detail of the original aggregate concrete surface:

Once painted, the natural coloration and surface is obscured.

Montgomery Center, 8630 Fenton Street (1970) Bucher-Meyer Photos by Clare Lise Kelly 10-31-16

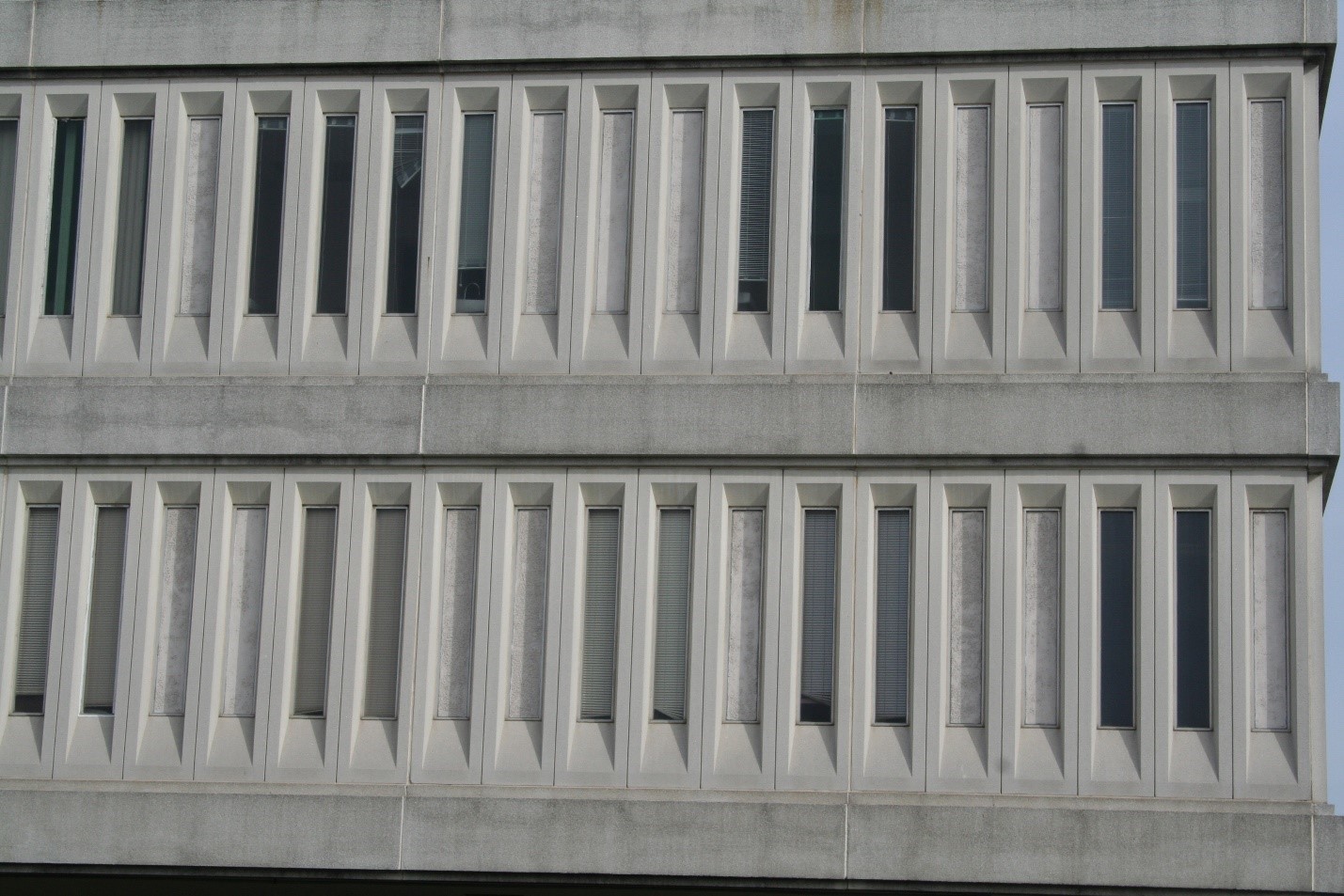

A well-preserved example of Brutalist design is found in this Takoma Park building. Though not a high-rise, the building clearly has a monumental nature characteristic of the esthetic.

Photo: Clare Lise Kelly 4-2013

The medical office building, at 831 University Boulevard, Takoma Park (1965) is cantilevered above an entrance podium. Asymmetrical placement of windows are regulated with vertical recessed elements that alternate windows with solid panels and establish a visual pattern that characterizes the building.

A well-preserved and rare example of a Brutalist school is the Bushey Drive School. The exterior walls of the experimental cylindrical school are loadbearing precast concrete panels. Each panel is eight feet wide, and two full stories high.

Photo: Clare Lise Kelly 2-1-2012

The Bushey Drive School (1961) Diegert and Yerkes; 4010 Randolph Road spawned the Round House Theatre group, named for its place of origin. For more, see the 2016 guidebook from our recent Montgomery Modern Bus Tour (pp 19-20 of the pdf).

You can also see examples of Heroic architecture in these high-rise hotels of the era:

Holiday Inn, 8777 Georgia Avenue (1971) designed by Anthony Campitelli

Marriott Hotel, 5151 Pooks Hill Road (1979) by Ward-Hall Associates

We have lost other noteworthy examples.

bing.com accessed 8-20-14

Wiscom Building (1964) 7550 Wisconsin Avenue

google streetview

The Wiscom Building, at Wisconsin Avenue and Commerce Lane in Bethesda, has lost its characteristic concrete sheathing, now replaced with glass.

Do you have a favorite Brutalist or Heroic building in Montgomery County?

Email me at clare.kelly@montgomeryplanning.org

For more information, see the book Montgomery Modern: Modern Architecture in Montgomery County, Maryland, 1930-1979 by Clare Lise Kelly (2015)

Other resources:

Mark Pasnik and Chris Grimley, Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston, 2015

Theodore H. M. Prudon, Preservation of Modern Architecture, 2008

Montgomery Modern explores mid-century modern buildings and communities that reflect the optimistic spirit of the post-war era in Montgomery County, Maryland. From International Style office towers to Googie style stores and contemporary tract houses, Montgomery Modern celebrates the buildings, technology, and materials of the Atomic Age, from the late 1940s through the 1960s. A half century later, we now have perspective to appreciate these resources as a product of their time.

Montgomery Modern explores mid-century modern buildings and communities that reflect the optimistic spirit of the post-war era in Montgomery County, Maryland. From International Style office towers to Googie style stores and contemporary tract houses, Montgomery Modern celebrates the buildings, technology, and materials of the Atomic Age, from the late 1940s through the 1960s. A half century later, we now have perspective to appreciate these resources as a product of their time.

Beth

I was born at Providence Hospital in ’58 and raised in Silver Spring. Even as a child, my eye was drawn to all of the above buildings, instinctively appreciating their uniqueness and looking forward to any opportunities to pass them while in the car.

Painting concrete? That’s a tough order to do correctly for even a garage floor. How does one do that for an entire building? It’s a shame that it was done.

Marcia L Stickle, Silver Spring Historical Society Advocacy Chair

831 University Blvd East also features a lovely atrium with a large filtered skylight.