Painful chapters of Montgomery County’s history played out at the Poor Farm and its associated cemetery south of Rockville along I-270. The Poor Farm was an almshouse surrounded by farm fields in use for nearly 200 years from as early as 1789 until the 1980s. Our county’s history is often difficult with regards to our historically vulnerable populations, like those that lived at the Poor Farm. Reading about these stories can be hard, but the Historic Preservation Program works to preserve and interpret these as part of our work to support a more equitable future for all of us. This work will be important with the expansion of I-270 around this historic site.

The Poor Farm’s difficult history

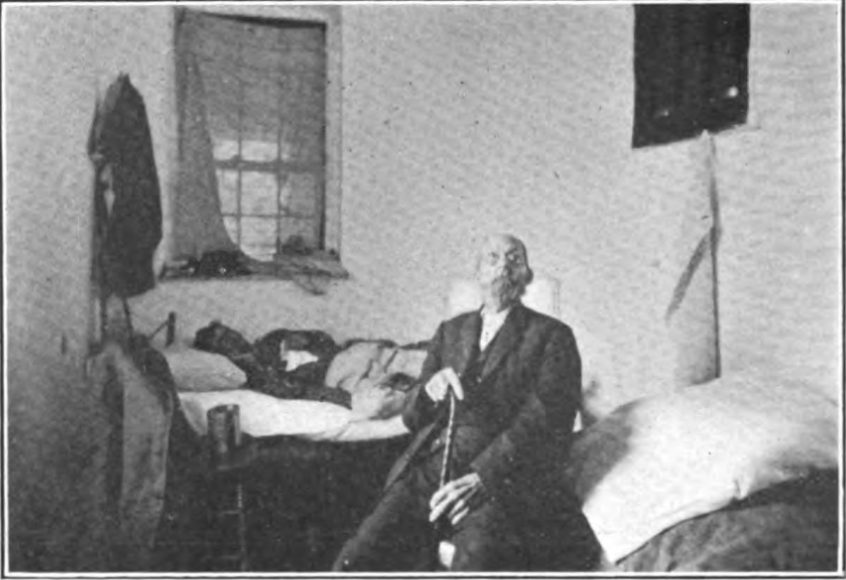

The Poor Farm was created in response to a 1787 Maryland Assembly act for the relief of the poor in Montgomery County. It was operated by the Trustees of the Poor and was intended to provide shelter for residents of the county who were thought to be unable to support themselves. It was a place where people who were homeless or suffering from mental illness, dementia, or physical disabilities were forced to live in sometimes nightmarish conditions (Figure 1). The 1787 act required inmates to wear the letters P and M in red or blue cloth on the shoulder of the right sleeve of their outermost garment; failure to do so could be punished by up to 15 lashes. A 1913 report described the buildings as “overrun with vermin and very insanitary in every way.” The residence building was apparently segregated by floor, and an 1877 report described the basement rooms reserved for African Americans as “overcrowded, dirty and offensive.” Some children were forced to sleep on the kitchen floor. When people died, their bodies were not always removed immediately.

Figure 1: Two people suffering from tuberculosis in the almshouse in 1913.

The Poor Farm Cemetery is formed

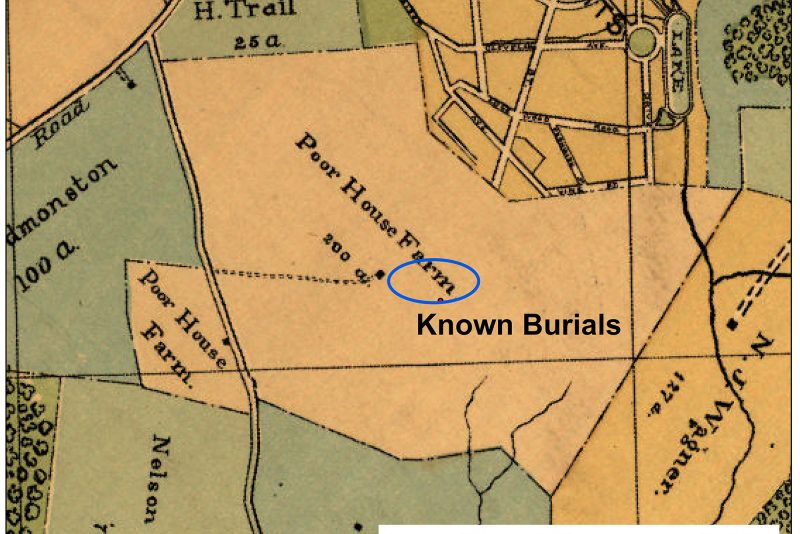

The almshouse site was expanded several times in order to meet increasing needs. The Trustees of the Poor for Montgomery County purchased 50 acres for the site in 1789. By 1882, it had grown to approximately 150 acres. In addition to at least one residence building, the grounds included outbuildings, farm fields, and a cemetery where residents were buried along with others from the county without any known relatives or whose families were not able to afford burial (Figures 2 and 3). The Poor Farm ceased operation in the 1950s and the main residence building was torn down in 1959. The county continued to use the cemetery to bury the homeless and other poor people into the early 1980s, but it was not maintained, and was sometimes the site of illegal dumping.

There were 47 people listed at the Poor Farm in the 1880 census, but other historical records suggest that typically between 20 and 30 people may have lived at the site at any one time including both Black and white people. While the number of occupants may never have been very large, it is possible that the total buried in the cemetery was in the hundreds. For example, the 1910 Census shows that six people died in the almshouse that year; if that was typical, the number of burials could exceed 1,000. The names of most of these people have been lost. Names we do know include John Diggs-Dorsey and Sidney Randolph—two of three known victims of lynching in Montgomery County who were reportedly buried at the Poor Farm in unmarked graves in 1880 and 1896. Viola Schaefer, who died in 1983, may have been the last person buried on site. Among those we cannot name are people buried in unmarked graves on the former Riggs Farm, once owned by a wealthy family who lived near Laytonsville. The Riggs family moved their ancestors’ remains to St. John’s cemetery in Olney when they sold the property in 1930. But more burials were found in unmarked graves in 1981 during development of the former farm into the Oaks Landfill. Snowden Funeral Home moved these graves to the Poor Farm. Their identities remain unknown, but since they were not moved by the family in 1930, it is likely that these were people the Riggs family had held in slavery. Specialists at the Smithsonian Institution attempted to identify those remains but were not successful.

Hundreds of unmarked graves remain

When Montgomery County sold the land to developers, they asked National Park Service archaeologists to investigate the cemetery. Archaeologists moved 60 to 70 graves in 1987 from a burial area within the original 1789 Poor Farm tract. Initial plans called for the bones to be analyzed, but that work was never completed, and the remains were reinterred in Parklawn Cemetery. Montgomery County paid for 38 more graves to be moved to Parklawn when construction crews uncovered them in 2000 during construction of the Tower building that stands on the site today. While parts of the cemetery may have been disturbed or covered by construction of Interstate 270, there are likely hundreds of unidentified graves that were not moved. No visible trace of the cemetery survives today.

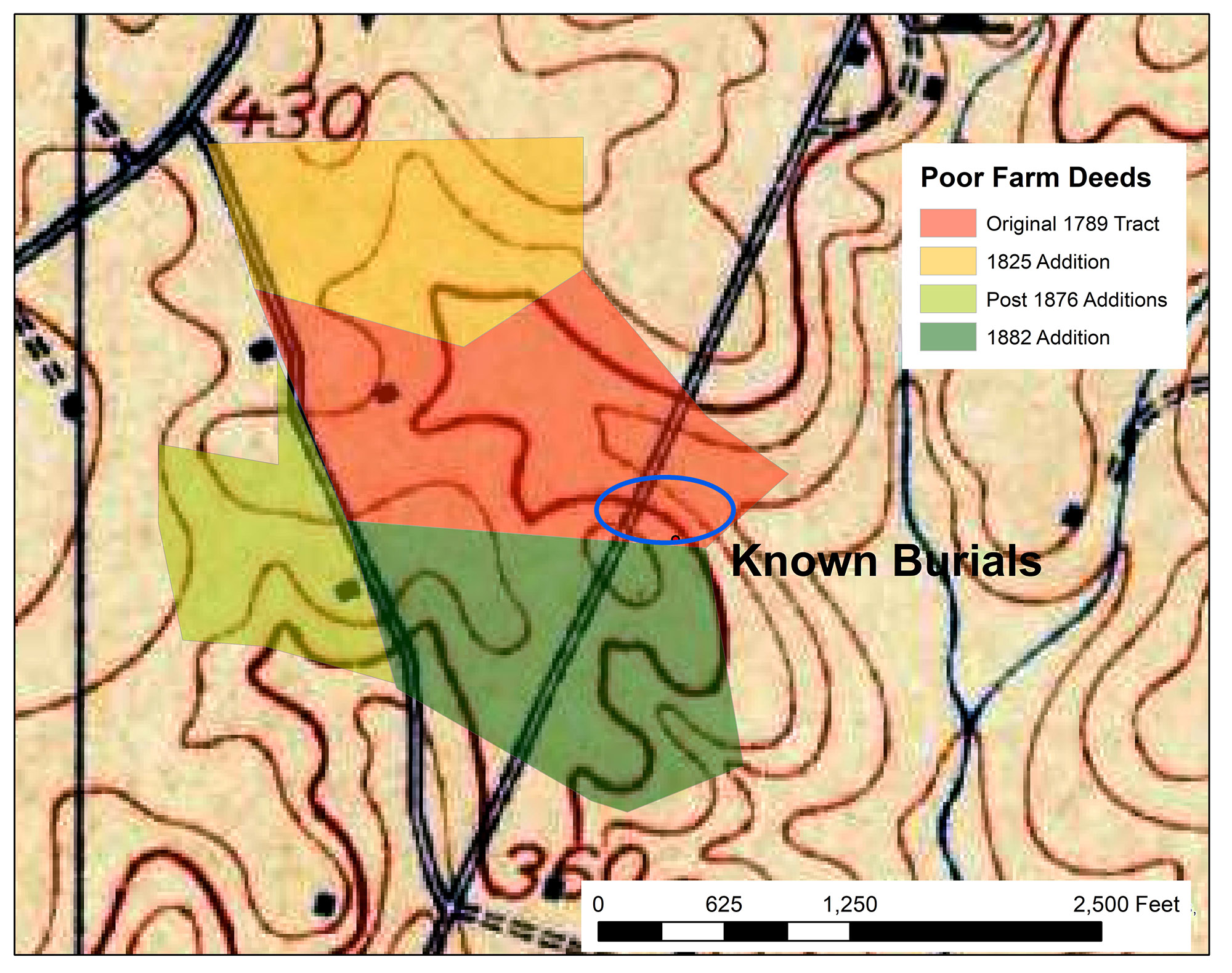

Montgomery Planning is researching the history of the site to help anticipate where there may still be graves at the former Poor Farm almshouse site. We have mapped the parcels purchased by Montgomery County for the almshouse between 1789 and 1882 (Figure 4). Topographic maps from 1908 and 1944 show that the known burials were found on a hilltop in the original parcel between 100 and 500 feet of a building shown on an 1890 map (Figures 3 and 4). This is consistent with where cemeteries were often sited in our county and suggests other areas where people might have been buried.

Figure 4: 1908 Topographic map overlain with parcels purchased for the Poor Farm over the course of a century (color shaded areas) and the area where burials were found in 1987 (blue oval).

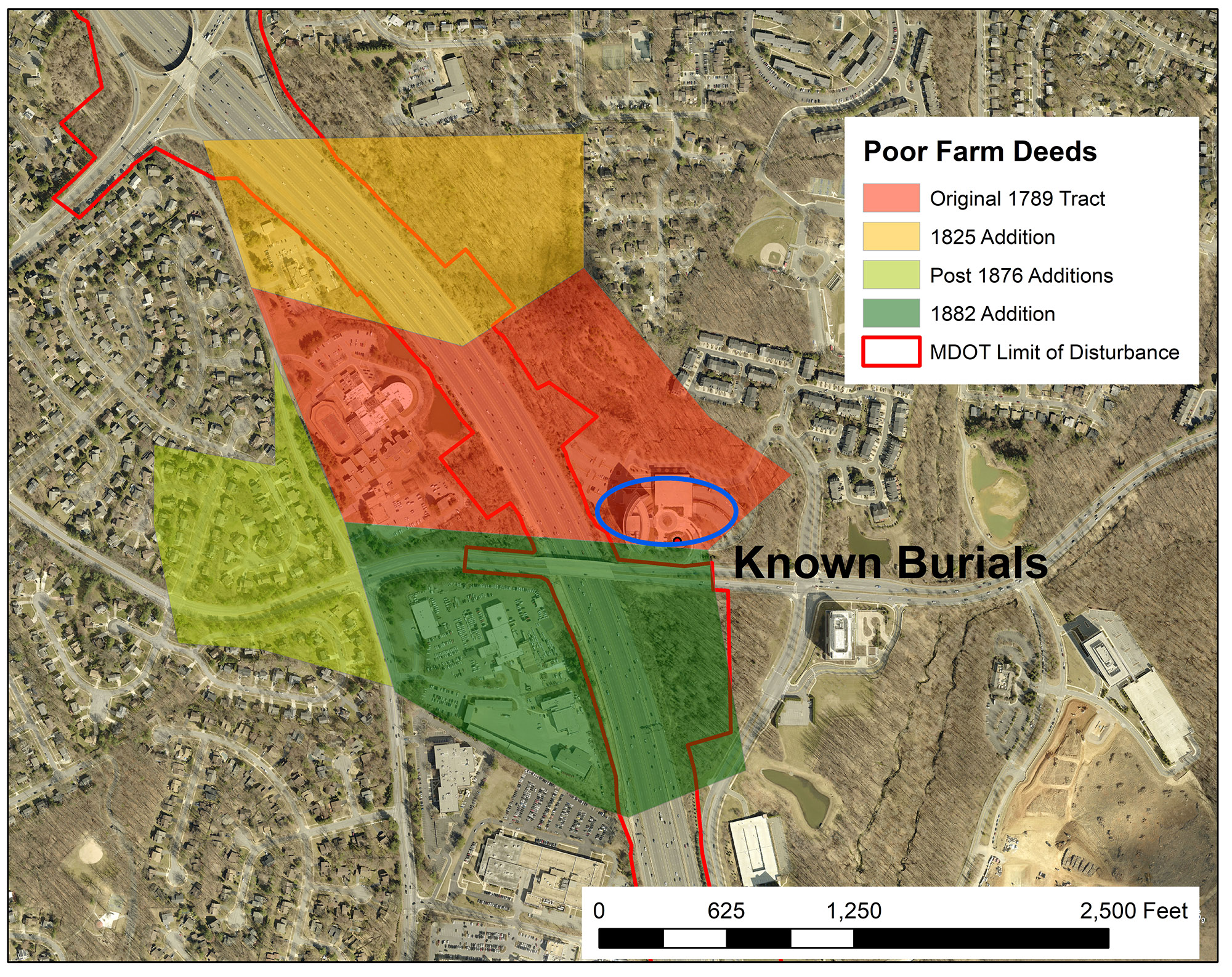

Potential impact of expanding I-270 on Poor Farm site

The Maryland State Highway Administration (MDOT SHA) is proposing to widen I-270 as part of the Beltway, I-270 Managed Lanes Project. Portions of the Poor Farm site are within the potential “limits of disturbance,” that is, the maximum area that might be affected by construction. The relatively high ground where graves were found in the 1980s is also found in parts of MDOT’s proposed project area within the original 1789 parcel as well as other parcels added in 1825 and 1882 (Figure 5).

Respecting remaining graves

MDOT SHA has stated its intention to conduct additional archaeological investigations in the vicinity of the Poor Farm Cemetery site to find out if any unmarked graves could be affected by the I-270 project. Montgomery Planning will work with MDOT SHA, any descendants, and members of the interested public to ensure that remaining graves are found prior to new highway construction. If burials are found, the remains will be treated with the respect that has been so long denied to them.

Figure 5: Proposed maximum limits of disturbance for expansion of I-270 (red outline) overlain on a 2019 aerial photograph with parcels purchased for the Poor Farm over the course of a century (color shaded areas) and the area where burials were found in 1987 (blue oval).

Tony Cohen

Hello Brian. Thank you for the enlightening article on the County Poor Farm. I am curious about the “P” and “M” lettering the inmates had to wear. What did the letters stand-for?

Thanks!

Brian Crane

Hi Tony,

Thank you for your question. According to a short article written about the Poor Farm by Patricia Abelard Anderson published in the Montgomery County Story in May 1998, the P and M stood for “poor” and “Montgomery.” The link to the full article is:

https://mchdr.montgomeryhistory.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12366/189/mcs_v041_n2_1998._andersen.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Brian