By Montgomery Planning staff

Montgomery Planning is celebrating Black History Month by sharing the voices, journeys, and impact of Montgomery Planning’s Black leaders.

Artie Harris worries that Montgomery County’s skyrocketing home prices will leave too many residents, including his two adult daughters, unable to afford a home in a neighborhood like the one where they grew up.

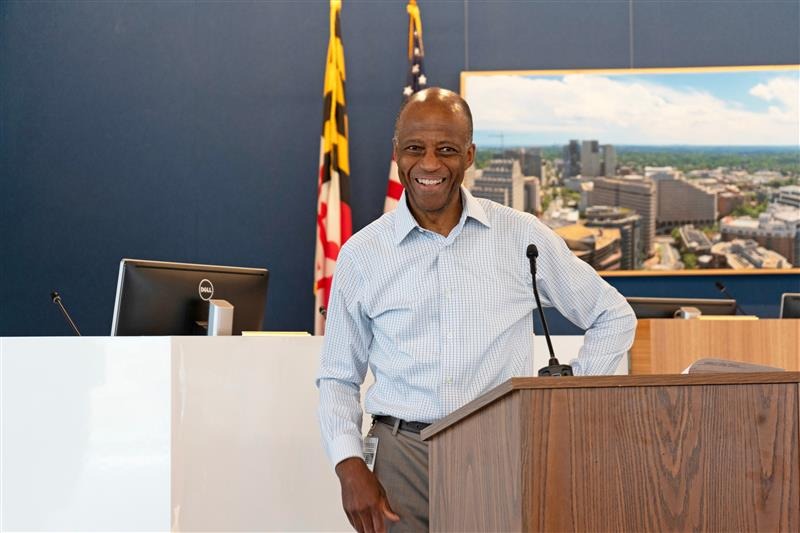

It’s one reason why helping the county get “unstuck” from its affordable housing crisis feels personal–and remains Harris’ top priority as chair of the Montgomery County Planning Board.

As Harris helps chart Montgomery’s future, he wants the county to offer more reasonably priced homes in all sizes, from large apartments for growing families to starter homes for young buyers and smaller spaces for downsizing seniors.

“It’s a matter of supply-and-demand. Housing costs come down when there is more of it,” Harris said. “And we need different types of housing to meet different needs at every stage of someone’s life.”

He envisions “complete” communities like the one where he’s lived for 26 years in Takoma Park. He treasures being able to walk to the food co-op, hardware store, pharmacy, restaurants, and a great bookstore, as well as catching public transportation and riding a bike through leafy parkland.

‘I felt a calling for that’

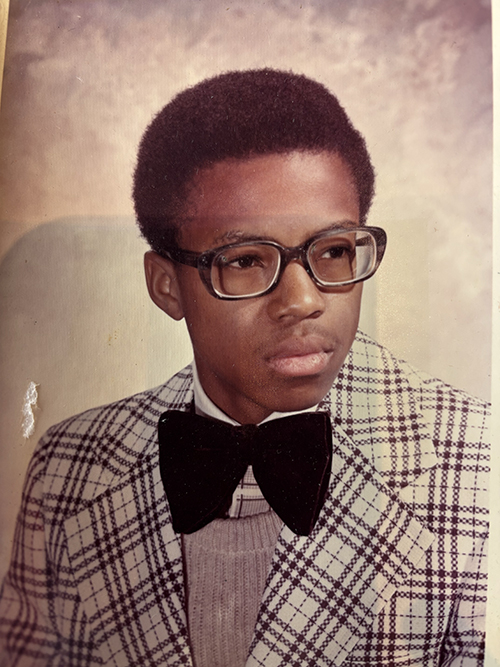

Harris grew up in Chicago. His mother was an elementary school teacher for the city and was required to go on mandatory unpaid leave when Harris was born. During that time, his father was enrolled in an apprenticeship program and was not yet earning a living wage. His family was fortunate to live in subsidized housing during that time– something he’s remained grateful for.

Harris grew up in Chicago. His mother was an elementary school teacher for the city and was required to go on mandatory unpaid leave when Harris was born. During that time, his father was enrolled in an apprenticeship program and was not yet earning a living wage. His family was fortunate to live in subsidized housing during that time– something he’s remained grateful for.

“I know the importance of having stable, quality housing,” he said. His father went on to work as a plumber for the Chicago Housing Authority, always going above and beyond to provide good service to the public housing residents.

His parents also taught him to look out for people even less privileged and to support local and national civil rights causes. “My father supplemented his income with a side plumbing business on evenings and weekends, and he always gave price breaks to people he knew couldn’t afford the full cost of the repairs,” Harris said. “My mother always responded to any need put before her— donating to community causes, serving as a court witness, contacting the alderman, and in countless ways helping others in her neighborhood and her church. They modelled giving back.”

Meanwhile, spending summers on his grandparents’ farm in rural Virginia made him “fall in love with nature and the outdoors.”

“In many ways when I’m walking through the woods and our parks, it gives me the same feeling as being on my grandparents’ farm,” he said. “I love being outdoors, and it gives me a kick to see all the ways our parks give people that connection to nature, whether it’s walking or biking on the paved or unpaved trails or kayaking in our lakes.”

His grandparents were pioneers as African-American farmers who owned their own farm in the 1930s. Like his parents, they were committed to service. They raised several foster children in addition to their four biological children, and his grandmother took it upon herself to ensure every family in their community had access to clean water—an achievement recognized with a fountain in her honor at the county courthouse.

Creating Communities

Harris worked for nine years as a civil engineer before turning his talent toward how real estate development and smart planning could help shape communities. He got his MBA from Stanford to equip his pivot to real estate development, where he has spent most of his career.

In the late 1990s, he moved to Maryland to become a vice president at Bozzuto Development Company. His work included spearheading a complex public-private partnership to restore the historic art deco Bethesda Theater on Wisconsin Avenue, construct apartment buildings above and behind it, and build a public parking garage beneath a portion of the buildings.

Tom Bozzuto, Toby Bozzuto, former Governor Martin O’Malley and Artie Harris in Baltimore, MD.

“That’s when I thought, ‘I really love being a developer, pulling partners together and leveraging assets to create communities,” he said.

In 2009, Harris became vice president of real estate for the nonprofit Montgomery Housing Partnership, which develops affordable housing in Montgomery and surrounding areas.

“It was giving back,” Harris said, that he loved the most. “There was a need, and I felt a lot of families weren’t as privileged as I was. I felt a calling for that.”

Inspired by Black History

Harris said he’s proud of Montgomery Planning’s work to highlight and protect the county’s rich Black history. That includes recently recommending historic designation for the Wheaton home of Romeo and Elsie Horad, who advocated for improved living conditions for Black residents in the 1900s and the Rose-Budd house, the ancestral home of founding settlers of several of the mid-nineteenth century free Black communities in the Sandy Spring area.

Harris said he’s proud of Montgomery Planning’s work to highlight and protect the county’s rich Black history. That includes recently recommending historic designation for the Wheaton home of Romeo and Elsie Horad, who advocated for improved living conditions for Black residents in the 1900s and the Rose-Budd house, the ancestral home of founding settlers of several of the mid-nineteenth century free Black communities in the Sandy Spring area.

“They’re inspirational to me,” Harris said of the Horads and other Black leaders throughout Montgomery’s history. “They say that we all have a part to play. We all need to help others.”

To recharge, Harris said he enjoys listening to jazz, reading biographies and history, cycling, kayaking and working in his garden. He also is active in his church along with his wife, Susy Cheston, who recently retired from working on women’s empowerment and business development around the world.

He said he’s excited to continue helping Montgomery plan for a future that is more affordable, livable, and economically vibrant.

He admits to being impatient – “I would love things to go much faster” – but at the same time, “I feel privileged to chair the Planning Board,” Harris said. “I’m always thinking about how we can do things better, how we can continue to make this county a great place to be in.”

Leave a Reply