Figure 1: Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park in Potomac Subregion

Master plans are created as ambitious visions for the future with recommendations for land uses, zoning, transportation, schools, parks, and other community facilities. We write them to guide development during the decades that lie ahead, using our best predictions of how population and priorities will change over those years. To assess the progress of a master plan, it’s beneficial to conduct a reality check as the master plan approaches its horizon date (20 years since adoption). A reality check can help us evaluate how well a master plan has been implemented, understand whether its visions have been achieved, and identify which recommendations worked as anticipated.

With these objectives in mind, the Montgomery County Planning Department initiated the Master Plan Reality Check project in 2017. The aim of this project is to assess the extent to which goals in master plans have been met. The first three plans studied were the Germantown Master Plan (1989), the Friendship Heights Sector Plan (1998), and the Fairland Master Plan (1997). Some recent plans, including the White Flint Sector Plan (2010), Bethesda Downtown Plan (2015) and Bicycle Master Plan (2018), have also included requirements for more frequent progress checks.

The latest plan we evaluated was the 2002 Potomac Subregion Master Plan. The Potomac Subregion plan area totaled approximately 66 square miles and was bound by I-270 and I-495 on the east, the Potomac River on the south, Seneca Creek to the west, and Darnestown Road and the City of Rockville to the north (see Figure 2). The primary challenges facing Potomac in 2002 included protecting environmentally sensitive areas, maintaining a low-density residential character, and enhancing park, recreational, and transportation links.

Overall, the Potomac Subregion Master Plan centered on the careful preservation of environmental resources and the strategic development of remaining vacant property.

Some of the key takeaways from a typical master plan reality check process include:

- Importance of data documentation: Planners should preserve data used at the time of master plan analysis to document their baseline assumptions.

- Greater understanding of economic conditions: More detailed market analysis should be conducted as part of a master plan to provide more quantitative data on baseline conditions and support for recommendations.

- Acknowledgment of flexibility: Plans reflect the time and place in which they are completed as well as the unique plan area characteristics, and this should be considered in the evaluation process.

- Prioritization of monitoring: Performing a master plan reality check before the horizon date can help determine whether incentives or other interventions should be considered to stimulate development.

We used both quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze all parts of the Potomac master plan, compiling data from a variety of sources. Findings from the Potomac reality check are outlined below, or to read the full report, visit Potomac Subregion Master Plan Reality Check.

Environment

Overall vision: Maintain and reaffirm a low-density residential “green wedge.”

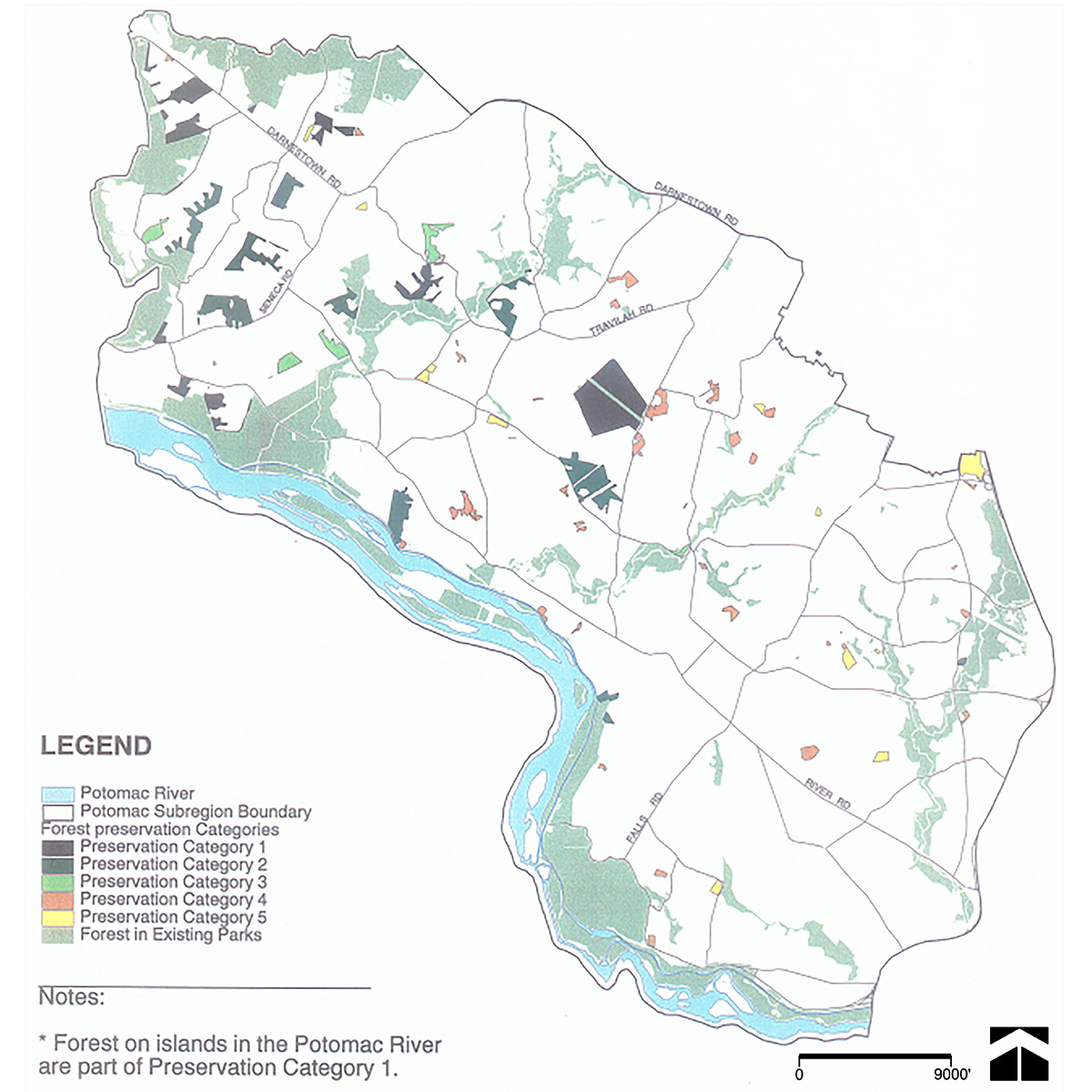

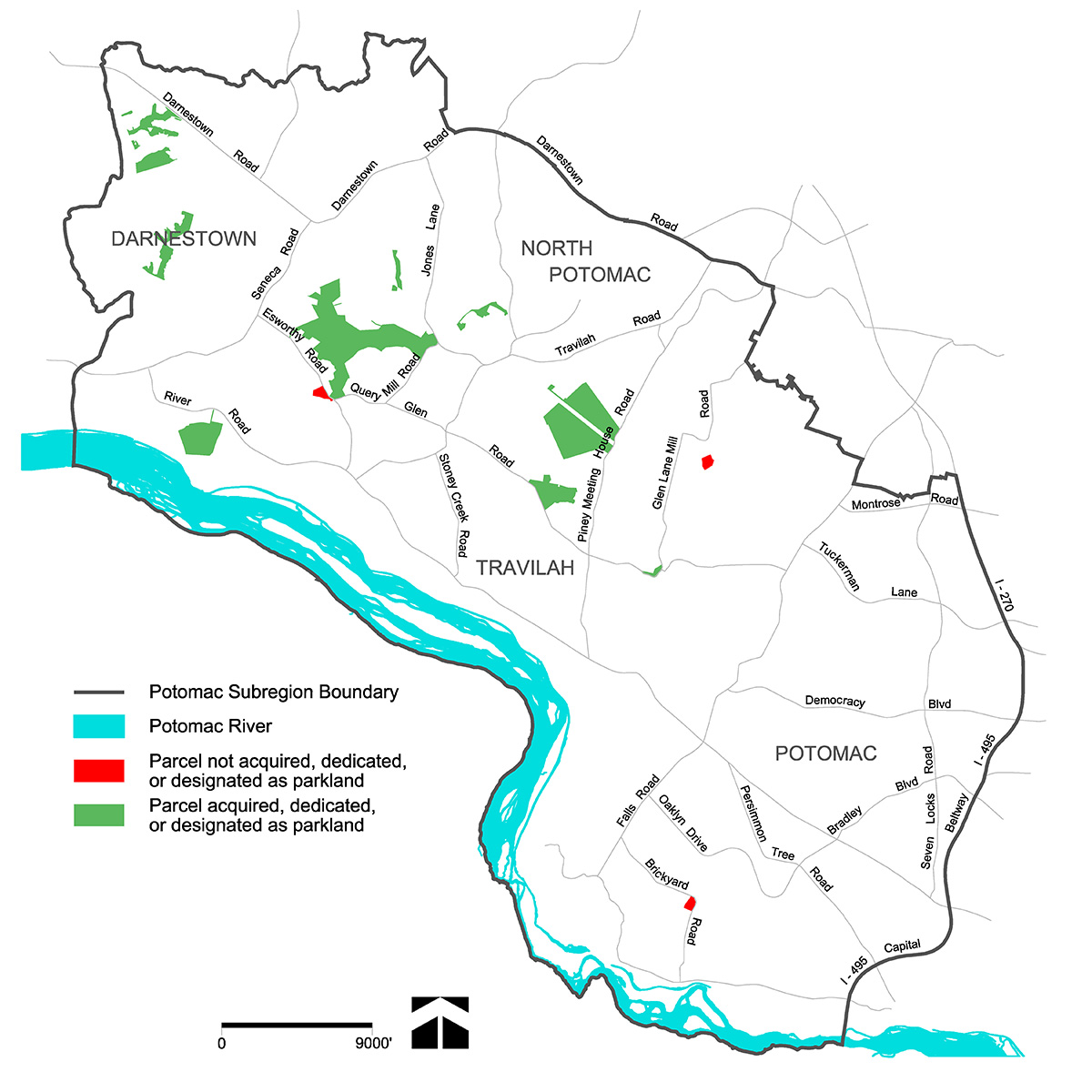

- Nine of 12 parcels recommended for acquisition as parkland have been acquired by dedication. Of considerable note were the acquisitions of the 258-acre Miller & Smith property and 65-acre Tipton tributary property, which are now the Serpentine Barrens Conservation Park (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

- The Plan recommended limitations to the extension of sewer service in areas zoned for low-density development. The restrictions have been followed, as seen by six denials or deferrals of water and sewer category change requests in Glen Hills in March 2023.

Land use and zoning

Overall vision: Strengthen and support the Subregion’s low-density residential communities.

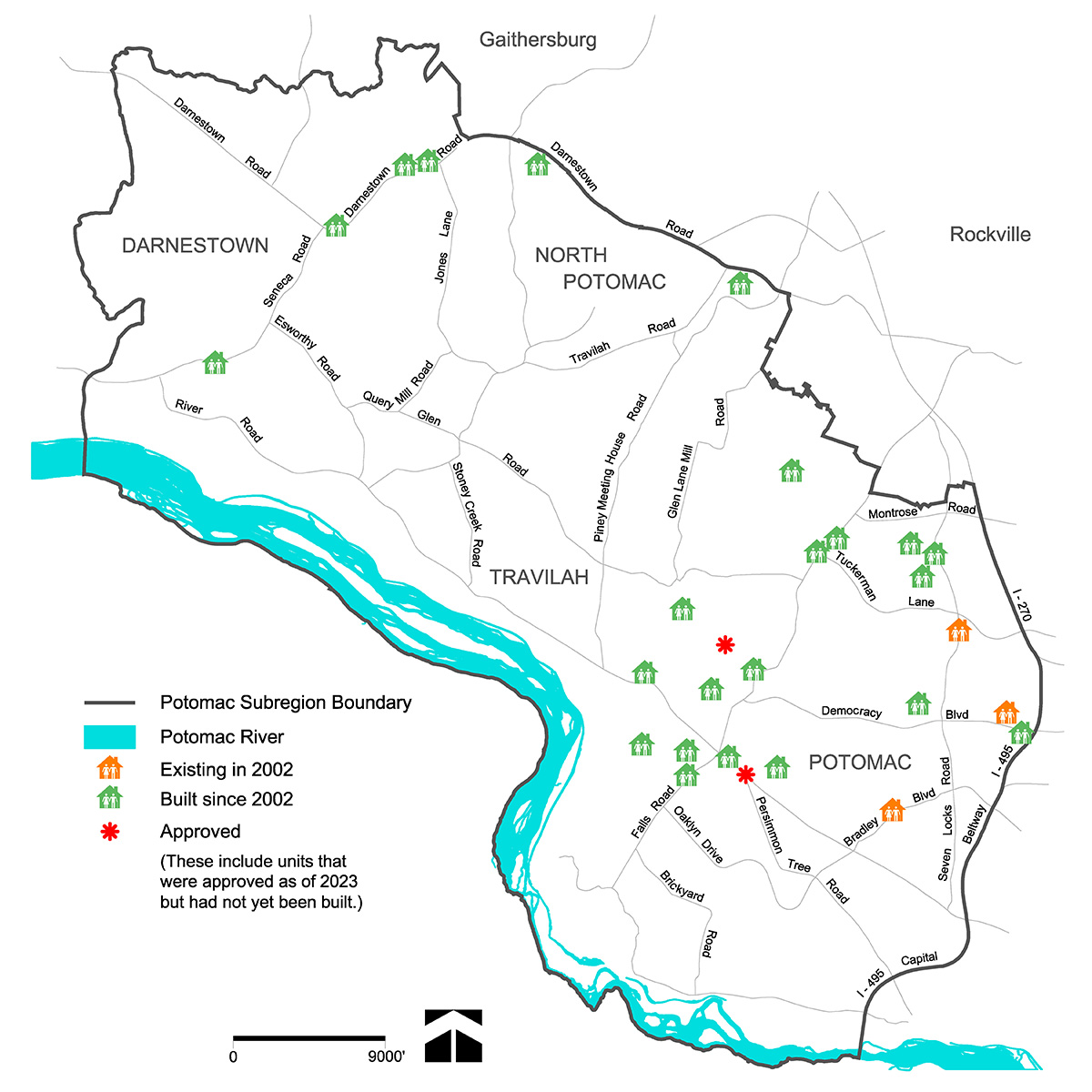

- The Plan recommended an additional 750 housing units for elderly residents be built within the Subregion’s boundaries. This recommendation has been met, as an additional 828 senior housing units have been built or approved since 2002 (see Figure 5).

- Recommendations for development on greenfield sites were fully implemented more frequently than recommendations for infill development. While Quarry Springs and Mount Prospect were built on vacant land and closely resemble the master plan vision, Potomac Village and Darnestown Village were already existing centers and have witnessed little to no change since 2002.

- Residential development has exceeded commercial development in the Subregion over the past 20 years. The Park Potomac development (Figure 6) exemplifies this trend as a site where dwelling units have been approved on a parcel originally designated as office use.

Figure 6: Residential Units in Park Potomac

Transportation

Overall vision: Maintain a transportation network that provides needed links and alternatives, while preserving the Subregion’s semi-rural character.

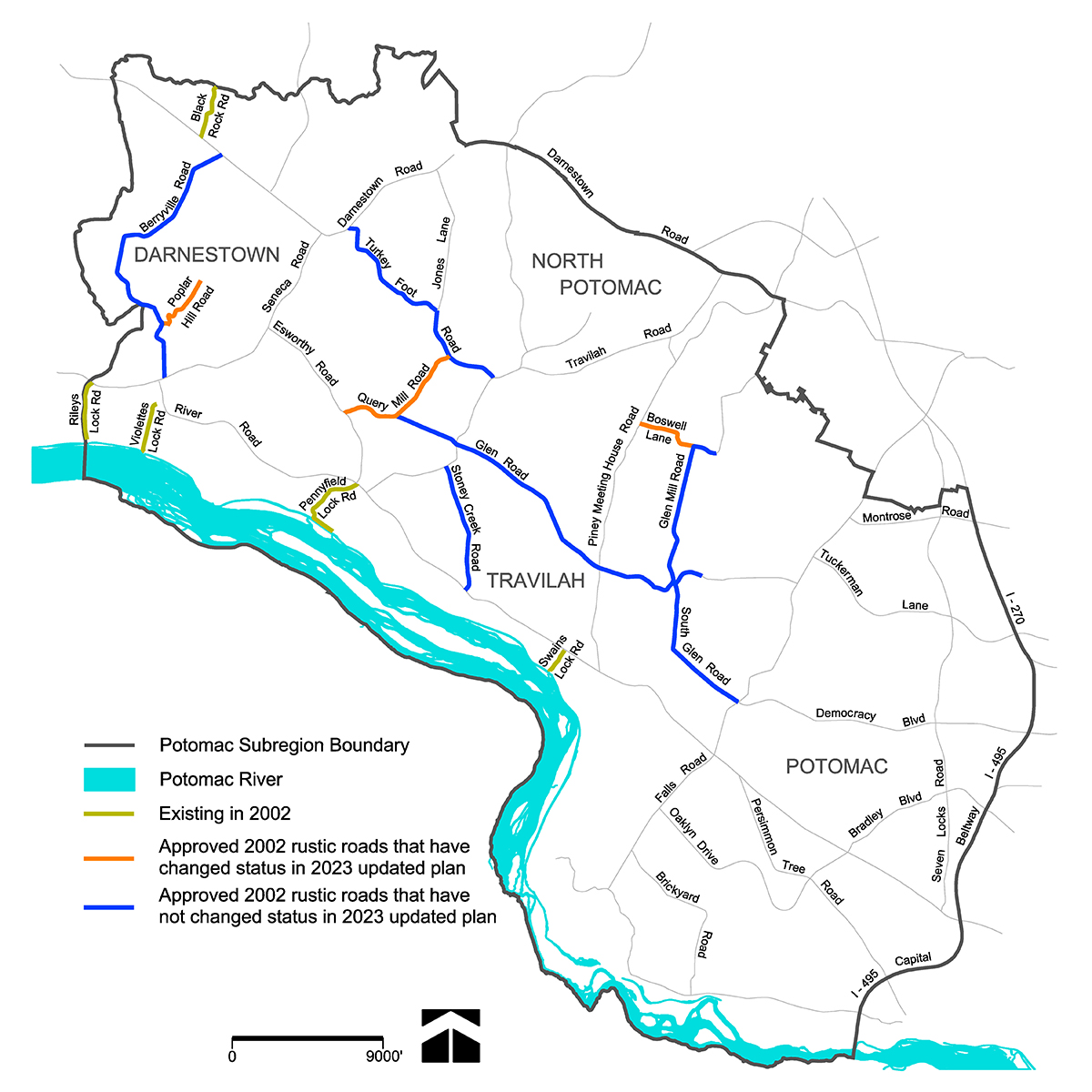

- Recommendations to preserve the Subregion’s semi-rural character have been met through the maintenance of the two-lane road policy and the designation of nine additional rustic roads (see Figure 8).

- As recommended in the Master Plan, two multi-modal transit centers have been built, and a Ride-On Route 301 bus has been added to reach residents of Tobytown.

- While 11 recommended bikeways have been added to the Bicycle Master Plan that was approved in November 2018, none of these bike routes has been fully constructed.

Figure 7: Query Mill Road, a Rustic Road in the Potomac Subregion

Community facilities

Overall vision: Establish and expand community facilities to provide needed services and foster a sense of community.

- The newly constructed Nancy H. Dacek North Potomac Community Recreation Center and significant renovation of the Bette Carol Thompson Scotland Neighborhood Recreation Center are examples of community facility recommendations that have been met.

- The Master Plan recommended repurposing surplus school sites as parks rather than building new sites. As schools have filled over the past 20 years, no sites have been declared as surplus nor converted to parks since 2002.

About the author

Bhavna Sivasubramanian is a housing research planner in Montgomery Planning’s Research and Strategic Projects Division. In her role, she conducts demographic, housing, and spatial analyses to inform ongoing master-planning efforts. Prior to joining Montgomery Planning, she enjoyed a career in international development, working on issues of food security and informal livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa and India. Bhavna holds a master’s degree in regional planning from Cornell University and a bachelor’s degree in international relations and economics from Tufts University.