Investors and technological giants are betting billions that Mobility as a Service will coax people out of vehicle ownership.

Investors and technological giants are betting billions that Mobility as a Service will coax people out of vehicle ownership.

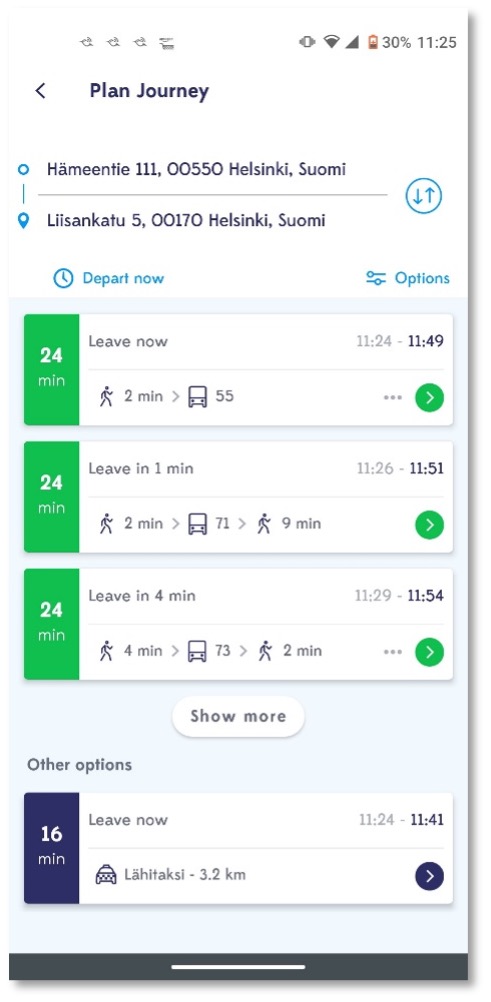

Example of a MaaS application allowing the traveler to view price and duration information for both private and public mobility options

Mobility as a Service (MaaS) is the idea that one does not need to personally own a vehicle to satisfy their mobility needs. It is a user-centric and technologically driven experience that seeks to integrate “a full range of mobility options in one digital-mobility-platform offering with public transportation as the backbone” (APTA, 2019). It moves beyond the current siloed mobility services (public transit, Uber, Lyft, Capital Bikeshare, Lime, etc.) to create a one-stop-shop for transportation services, integrating a variety of mobility options and payment methods, into a single application. To achieve this, cities such as Helsinki have passed laws that require all providers of transportation services, both private and public, to release open and free application programming interfaces (APIs) for seamless integration into MaaS applications (Bonfils, 2019). What impact would a widely adopted MaaS transportation ecosystem have on the quality of life for residents in Montgomery County? Will it make it easier or more difficult for the county to meet its transportation goals?

Why all the recent attention regarding MaaS? The transportation industry is at a crossroads of multiple technological advancements. Innovations in big data, communications, energy production and storage, computer processing, sensor-perception systems, machine learning, and artificial intelligence have the potential to revolutionize the transportation industry. It is estimated that the levels of disruption and innovation in the transportation industry in the next 12 years will exceed those in the previous 50 (McKinsey & Company, 2019). With the ubiquitous adoption of smartphones and seamless sharing information via the “internet of things” (Iot) and the emergence of the “sharing economy,” the concept of Mobility as a Service (MaaS) is growing in popularity. Since 2010, approximately $56.2 billion has been invested in ride-hailing services, a key component of a MaaS ecosystem.

Total Disclosed Automotive Investments since 2010 across 10 technology clusters1

We have already seen components of a MaaS ecosystem come to fruition in Montgomery County. We are all familiar with ride-hailing companies such as Uber and Lyft, which since 2010 have had a profound impact on the transportation system. In addition, Waze offers a direct peer-to-peer (P2P) car sharing application that follows the Airbnb model. Shared micromobility has also had a significant impact in parts of the county. For example, in 2020 in the county, almost 24,000 more trips were made on dockless vehicles, predominantly e-scooters, than via traditional docked bicycles. Shared micromobility “enables users to have short-term access to a mode of transportation on an as-needed basis,” typically in the form of a traditional or electric bike or electric scooter (Shaheen, Cohen, 2019). There is evidence that shared micromobility provided needed transportation services during the pandemic. Both the number of trips and the average trip distance steadily increased from May of 2020 through July of 2020 during the heart of the pandemic. This may suggest that micromobility provided a valuable mobility option for citizens who still needed to work and travel during the pandemic. Finally, Ride-On now offers “Flex,” an on-demand transit service that operates in two zones in the county.

Micromobility Trips Beginning or Ending in Montgomery County2

Many people, particular urbanites, depend on these existing mobility services (ride-hailing, shared micromobility, and transit) to live a car-free life. Large technology and automotive companies and investors are betting big bucks, however, that the promise of a connected and autonomous vehicle future will loom large in the success of the MaaS business model, which has yet to prove profitable in both urban and suburban environments. In 2018, “travelling by Uber or other ride-hailing services costs around $2.50 a mile; but take away the driver, and that cost could fall to $0.70 a mile” which is comparable or slightly cheaper than existing car ownership costs (The Economist, 2018). In 2019, Tesla CEO Elon Musk predicted that robotaxis “would be less than 18 cents per mile,” well below the cost of owning and operating a traditional private automobile (Boyle, 2019).

One of the most bullish analyses conducted to date estimated that robotaxis “will offer vastly lower-cost transport alternatives — four to 10 times cheaper per mile than buying a new car and two to four times cheaper than operating an existing vehicle” (Arbib and Tony Seba, 2017). An academic analysis, however, conducted by researchers at MIT in the San Francisco area found that conventional driven vehicles’ “total cost of ownership is a remarkably low 72 cents per mile, whereas the high licensing, insurance, cleaning, and safety oversight costs associated with autonomous taxis combined with the low (52 percent) utilization rate of the current taxi fleet means robotaxis are likely to cost between $1.58 and $6.01 per mile” (Neidermeyer, 2019). Clearly the jury is still out whether large fleets of robotaxis can tilt the economic scale and impact private vehicle ownership by significantly lowering peoples’ travel costs.

Micromobility Trips Beginning or Ending in Montgomery County July 2019 - May 2021 (Excluding Capital Bikeshare)

What is certain, however, is that mobility options available to you in your travels have increased dramatically during the past two decades and will likely continue to diversify. California has recently provided a process for ride-hailing companies to charge fees for autonomous taxi rides (pending a lengthy approval process). In Phoenix, Waymo is providing Level 4 autonomy (fully autonomous transportation) to customers in a “in a 50-square-mile area in the suburbs of Chandler, Tempe, and Mesa” (Crowe, 2020). Motional and Lyft, which completed 100,000 supervised paid self-driving taxi rides in Las Vegas since 2018, recently announced plans to launch “fully driverless robotaxi services in major U.S. cities in 2023” (Korosec, 2020).

The amount of impact that connected and autonomous vehicles will have on future transportation metrics (vehicle miles traveled, vehicle hours of delay, safety, equity, and others) will partly depend on future ownership models. Federal and state governments will be especially in position to leverage the MaaS business model to help mitigate climate impacts. For example, the slow rate at which vehicle fleets turnover is problematic in reducing greenhouse gases from the transportation sector in the near term. In 2018, approximately half of the light-duty vehicle fleet in the Washington, DC area was older than eight years (see chart below). If a MaaS platform is successful at delivering an on demand, safe, cheap, and reliable mobility service, car ownership rates may precipitously fall, particularly in urban areas. RethinkX estimates that robotaxis would be used 10 times more than individually owned vehicles, greatly reducing the number of cars needed to be retired and replaced with electric vehicles (Arbib and Tony Seba). Policies could be put in place to mandate robotaxi services operate only electric and/or hydrogen powered vehicles.

Composition of Passenger Vehicles by Model Year in 2018 in the Washington, DC Region3

Composition of Passenger Vehicle Fuel Types by Model Year in 2018 in the Washington, DC Region3

So, what would it take for you to give up your car for an app? If MaaS provided a safe, reliable, and on-demand mobility ecosystem that cost less than maintaining your private vehicle, would you be tempted? Although the timing is unknown, it seems inevitable that robotaxis will make an appearance in the Washington, DC region. It is also clear that an increase in mobility options will continue to place pressure on local transit agencies to evolve, strategize, and place an emphasis on high-quality transit options to keep pace with technological advancements in the private sector.

[1] McKinsey & Company (2019). Start me up: Where mobility investments are going, New York, New York.

[2] 2019 Dockless trip data (Dockless E-Bike (Non Capital Bikeshare & E-Scooters) is from June 27 through December 31. Data feeds were suspended from June 2, 2020 through June 9, 2020. In addition, 53,779 dockless Capital Bikeshare trips occurred in 2020 that could not be located due to a lack of location information.

[3] Washington Council of Governments (2021). 2017/2018 Regional Travel Survey Public Files.

About the author

Russell Provost is a Planner Coordinator with the Countywide Planning and Poicy Division at the Montgomery County Planning Department. Russell Provost received his bachelor’s degree from Virginia Tech in Public and Urban Affairs and Master’s degree in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Florida. Russell specializes in operationalizing planning theories and concepts using geographical information systems (GIS). Russell currently assists staff with advanced GIS analyses to measure the performance and connectivity of multi-modal transportation systems.