Even the most forward-thinking land use policies will fail if they are not supported by transportation infrastructure and services that reinforce – or at least don’t undermine – their objectives. As the Wedges and Corridors plan recognized more than half a century ago:

“An efficient system of transportation must include rapid transit designed to meet a major part of the critical rush-hour need. Without rapid transit, highways and parking garages will consume the downtown areas; the advantages of central locations will decrease, the city will become fragmented and unworkable. The mental frustrations of congested highway travel will take its toll, not to mention the extra costs of second cars and soaring insurance rate. In Los Angeles where an automobile dominated transportation system reigns supreme, there is still a commuter problem even though approximately two-thirds of the downtown section is given over to streets and parking and loading facilities. There is no future in permitting the Regional District to drift into such a ‘solution.’”

Montgomery County has failed to make significant progress in reducing the proportion of people who get to work by means other than driving alone, lagging other area jurisdictions (American Community Survey, 2019, 5-Year Estimates).

Despite this prescient warning, we remain heavily dependent on driving, a dependence rooted in generations of efforts to help cars move as quickly as possible. Successive road “improvements” have added more and more lanes for vehicles at the expense of space for pedestrians, bicycles, dedicated lanes for transit vehicles, street trees and anything else that might slow cars. This makes alternatives to driving less practical and appealing, which leads to more driving and generates demand for wider roads.

Reinforcing this vicious cycle is the fact that optimizing major arterials for cars has made these corridors unattractive and unsafe, discouraging private investment and compact, transit-oriented development even where high-quality transit infrastructure is already in place (as evidenced by several large underutilized properties along corridors in close proximity to Metrorail stations).

The most obviously damaging consequence is that pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers are killed or seriously injured with disturbing frequency. Somewhat more subtle, but perhaps just as significant, is the effect that automobile-oriented design has on the vitality and appeal of neighborhoods and commercial districts alike. Safe, attractive streets encourage people to get out and walk, roll, or bicycle, whether simply to get some exercise, to run an errand, to go to work or school, or to reach an intermediate destination such as a bus stop or rail station. This kind of activity supports physical and mental health and facilitates the casual social interactions that build a sense of place and community. Ugly, unsafe roadways are barriers that degrade the quality of life of everyone who lives and works near them, even if those people are never involved in a traffic collision and even if they do not personally enjoy walking, rolling, or bicycling.

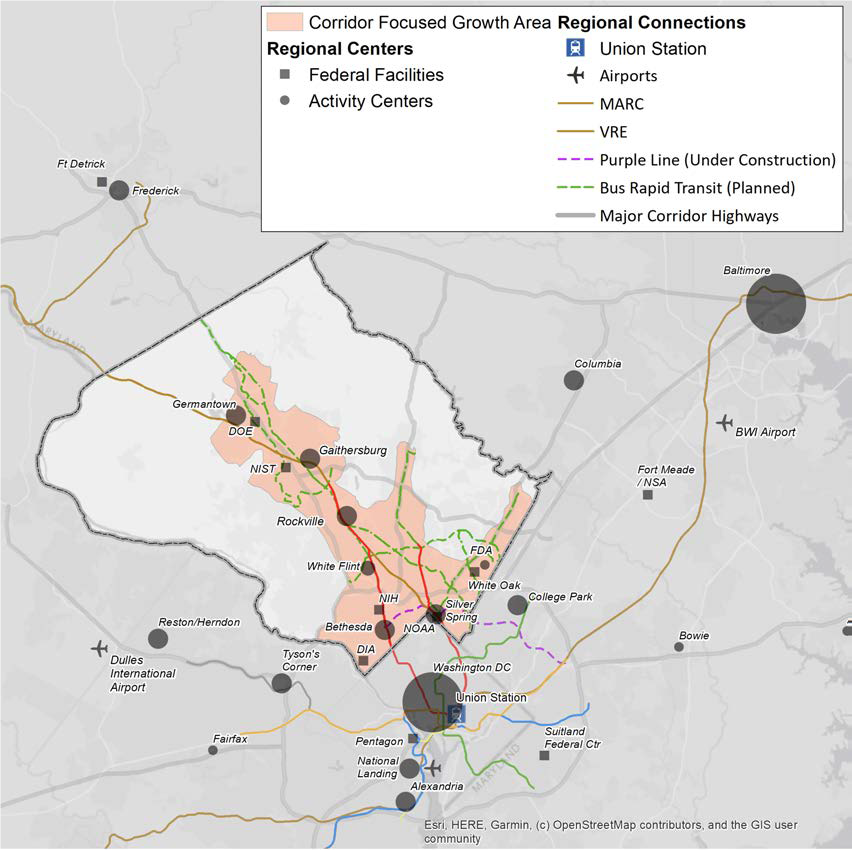

The hub and spoke model of arterial corridors was a logical way to link suburban enclaves to jobs in and around the District of Columbia, but other important centers of activity have emerged. Our prosperity depends on access to Frederick, Prince George’s, Howard and Baltimore as well as Arlington, Fairfax and Loudoun. The lack of efficient transit connections to these important centers of economic, intellectual and social activity leaves us unable to take full advantage of our presence in one of the most dynamic regions in the country, if not the world.

More and more residents and workers prefer transit and other alternatives to driving alone – and a significant number do not have access to a car – but most jobs in the county are not located near high-quality transit, and many of our neighborhoods lack even sidewalks. Combined with the absence of efficient east-west connections, especially for transit riders, this pattern limits access to jobs and opportunity, particularly for low-income residents who are more likely to depend on transit and makes our transportation system less adaptable and resilient.

About 40% of federal jobs at government agencies and 30% of jobs at private employers in Montgomery County are within ½ miles of a Metrorail or MARC station.

The failure to provide robust alternatives to driving and the inability to provide additional space for roads – in combination with low rates of housing construction – leaves more commuters stuck in traffic and pushes jobs as well as people to other jurisdictions. The result is that the county loses residents, jobs and tax revenue while simultaneously increasing traffic congestion as more people drive through the county on the way to jobs and homes in other places.

This is why Thrive Montgomery proposes reorienting our transportation policies around:

- Developing a safe, comfortable, and irresistible network for walking, biking, and rolling. We recommend expanding the street grid in downtowns, town centers, and suburban centers to create shorter blocks and transforming the road network by incorporating complete streets design principles with the goal of eliminating roadway fatalities and severe injuries and supporting the emergence of more livable communities.

- Building a world-class transit system. Thrive Montgomery envisions a network of rail, bus rapid transit and local bus infrastructure and services that make transit the fastest, most convenient, and most reliable way to travel to major centers of activity. It calls for prioritizing connecting historically disadvantaged people and parts of the county to jobs, amenities, and services with improved transit service.

- Adapting policies to reflect the economic and environmental costs of driving alone. The plan proposes the use of pricing mechanisms, such as congestion pricing or the collection and allocation of tolls to support walking, rolling, bicycling and transit. It also recommends market-oriented provision and pricing of parking.

Transit, walking, rolling, and biking are critical to “complete communities” that have the amenities, sense of place, and level of activity that more and more people of all backgrounds and ages are seeking. Transit exerts a gravitational pull on real estate development by creating incentives and opportunities to locate a variety of uses, services, and activities near station locations – and to each other. By the same token, successful mixed-use centers require a transportation scheme that supports modes of travel appropriate to the trips users need to take. For example, a rail-based transit line may connect jobs to housing in different parts of the county or region, but sidewalks and bikeways are better suited to connecting offices to shops, restaurants, or apartment buildings in a town center or between a downtown and the surrounding residential neighborhoods.

The point of Thrive Montgomery’s emphasis on alternatives to automobile travel is not to eliminate driving but to make short trips around town by bicycle or bus safe and appealing. A quick trip to the grocery should be manageable on foot, while a visit to another town might require a trip by car, train, or even airplane. The most desirable places to live and work are the ones that offer a menu of choices that make all sorts of travel effortless and delightful while supporting best practices in land use rather than relying on a single mode of travel at the expense of every other consideration.

A future post will discuss why adding connections to complete street grids in downtowns, town centers, and mixed-use communities is so important to creating more livable places – but first we’ll take a look at Thrive Montgomery’s recommendations on housing, parks and recreation.

About the author

Casey Anderson has served on the Montgomery County Planning Board since 2011 and was appointed Chair in 2014. He also serves as vice chair of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the bi-county agency established by state law that regulates real estate development, plans transportation infrastructure, and manages the park systems in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties.

Dick Stoner

As someone who has a copy of the original wedges and corridor plan document, I marvel at how times have changed. No one could have imagined how transportation by car would evolve, and how Metro as well as pedestrian facilities would change over time. The suburbs were a place where your car took you to the edge of rural areas which were quiet at night and where trees and wildlife were the norm. Now, suburbs are employment centers and people move daily in all different directions between those wedges and corridors which were seen as pathways into the Nations Capital. Every resident of every neighborhood should weigh in now on what seems best for their areas. It’s not a monolithic suburban area.