Recent analysis of three past plans reveals goals for housing and public facilities were accomplished, while visions for commercial spaces and transit have been slower to achieve

Planning, by design, is a forward-looking field and with 20 to 30-year plan horizons. Planning departments don’t often look back to see what happened with their visions. Such analysis is usually too challenging – staff who have worked on the plan have moved on and departments don’t often have the capacity or resources to handle such a task along with their day-to-day planning work.

The Montgomery Planning Department, however, decided to tackle this task in 2016 with three plans. We wanted to find out what had happened in different types of plan areas to see if our recommendations had materialized as the plans envisioned they would. The purpose of this project was not to render any sort of value judgment on past plans, but simply assess the outcomes from the plans and to what extent they met their goals across six categories of indicators: residential development, non-residential development, community facilities, urban design, transportation, environment.

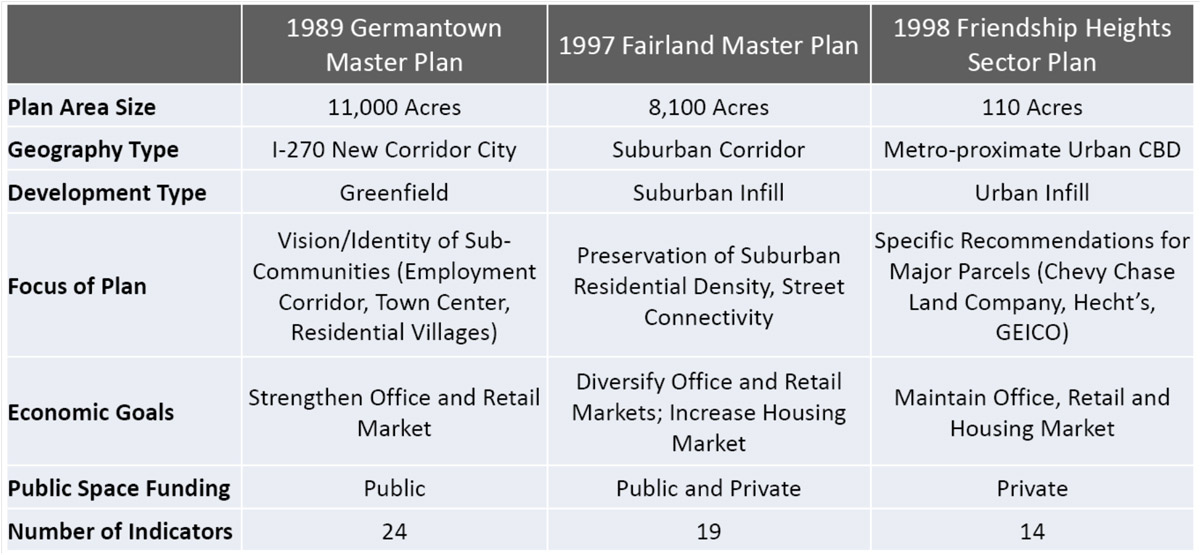

Three plans were selected for study: 1989 Germantown Master Plan, 1998 Friendship Heights Sector Plan, 1997 Fairland Master Plan. These plans were selected because they were past their horizon date, represented different types of county geographies and plan types, and sufficient data was available for analysis.

The study produced several interesting findings.

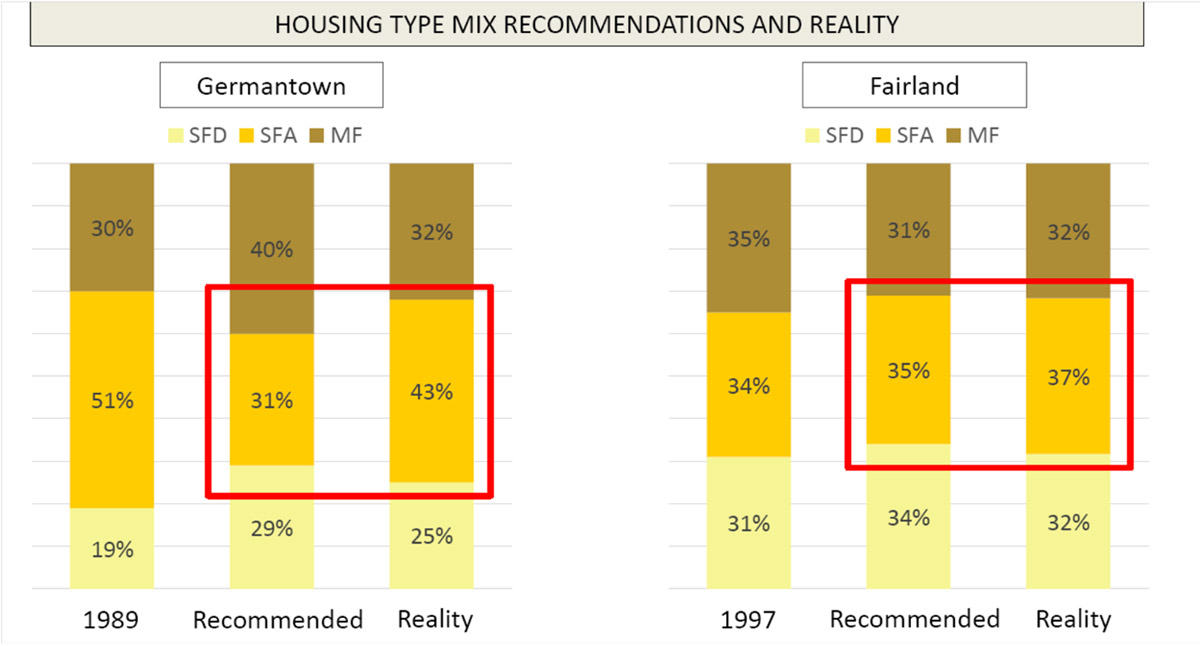

Residential development generally achieved overall unit goals, but was less effective in altering unit type mix in Germantown and Fairland. The plans for these two communities envisioned a shift in the housing mix from townhouses to single-family detached units. For example, the Germantown Plan recommended 31 percent townhouses, but today has 43 percent. This figure is still down from the 51 percent in 1989 when the plan was adopted.

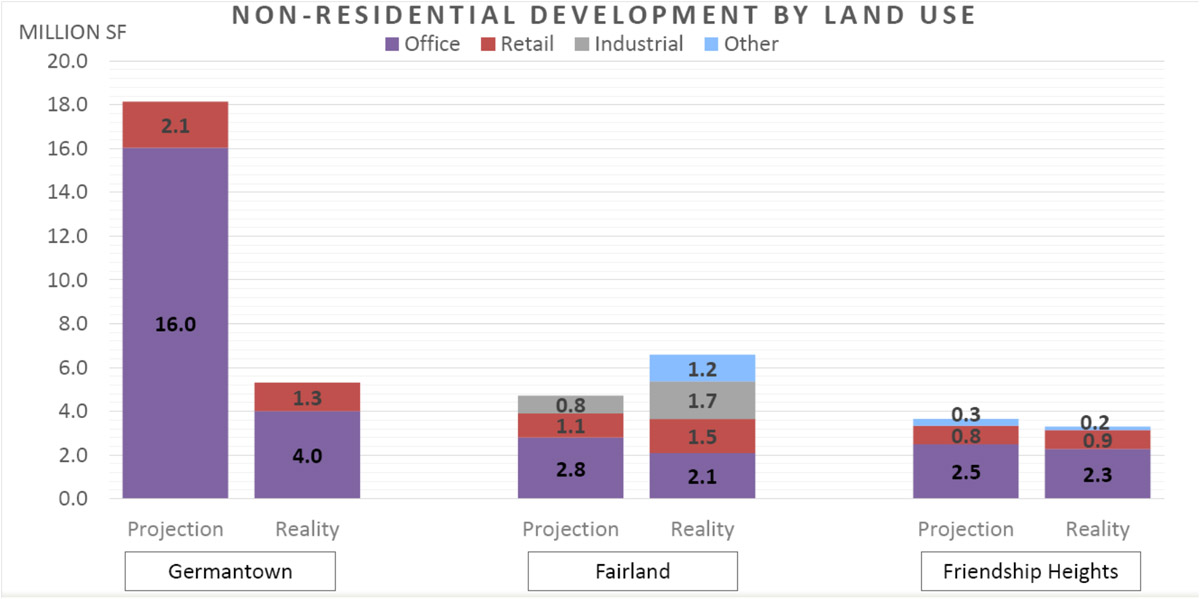

Commercial build-out depended on the market and differed in plans for urban areas versus suburban areas on the basis of floor area ratio (FAR). Total commercial development generally met expectations in Friendship Heights (3.3 million square feet) and Fairland (5.3 million square feet). The commercial build-out in Germantown fell significantly short of expectations with only 5.3 million square feet of commercial uses compared to a projection of 18.1 million square feet in the plan.

Most of the capital commitments in plans for schools, parks and community facilities were delivered by the public sector as envisioned. This realization includes a greenbelt park and a library in Germantown, and an elementary school site and a playground at the Cross Creek Club local park in Fairland. Capital commitments that required private sector redevelopment and investment, such as a park in Friendship Heights on the GEICO site, had a mixed experience. As the GEICO site has not yet been redeveloped, the park was not created.

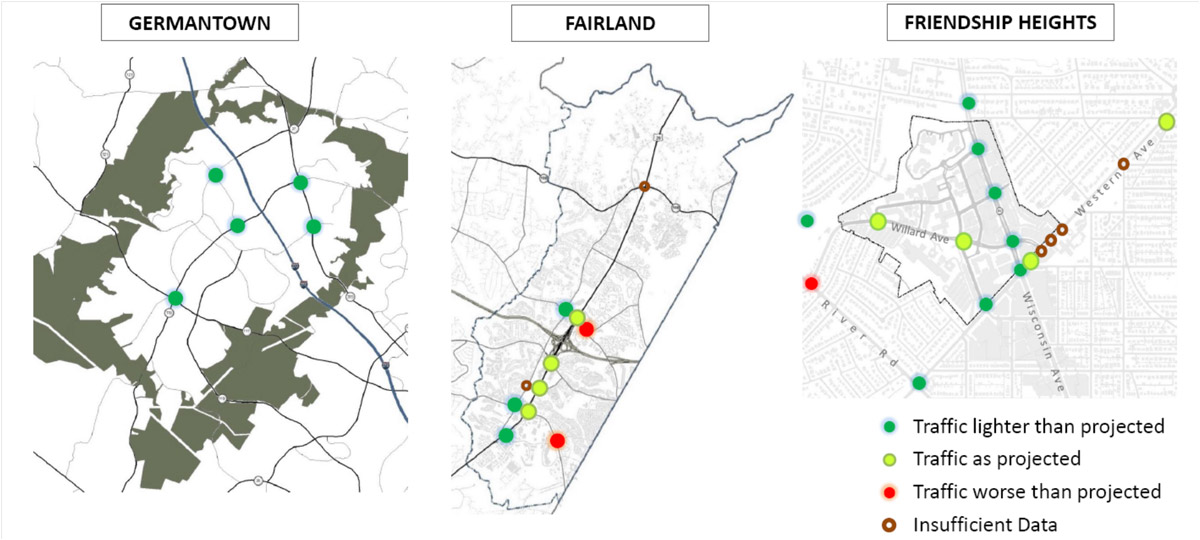

While traffic flow was as good or better than projected in all three plans, investment in transit and pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure has not materialized as quickly as hoped. Only two intersections in Fairland and one in Friendship Heights were found to be worse than projected. Some investments and pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure have been made in all plan areas. Similar with parks, some of the investments required private sector redevelopment, which did not always materialize. The suburban land use typology in Fairland also made the goal of greater connectivity more challenging.

It is also notable that the plans did not mention any concerns about school overcrowding and affordable housing, which are often priorities in recent plans. The Germantown and Fairland plans identified sites for new schools, which have been reserved. The Friendship Heights plan did not discuss schools at all. Similarly, the plans did not prescribe goals for affordable housing. This finding demonstrates how strongly plans are products of the issues of their time.

So what does this mean for how we plan in the future? One main key takeaway from the Master Plan Reality Check was to provide more data and market analysis in plan appendices to document assumptions about the future. It was challenging to go back and try to distill the rationale behind decisions when data was unavailable. Economic analysis helps assess the baseline conditions for a plan’s early years, but it shouldn’t be a limiting factor as plans set visions for 20+ year horizons, much longer than any economist can predict with much accuracy. Even so, such analysis can help set expectations as to how quickly development might materialize and the temperature of the local market.

Finally, the Master Plan Reality Check helped new indicators for master plan monitoring. While change takes time to measure, performing monitoring on select metrics before the 20-year horizon date of a plan can help determine if modifications to plans are necessary to stimulate development and physical improvements to the area.

Acknowledgements to Nick Holdzkom, Senior Research Planner, and Hye-Soo Baek, University of Maryland Graduate Student Intern for their significant work on this study.

MB Dohlie

I dare you to review lack of achievements in the previous Bethesda Downtown Sector Plan. The achievements are pitiful in terms of infrastructure – schools, roads/traffic/ pedestrian and cyclist safety; the lack of public amenities, planned for or never planned for; the lack of green space and parks for good public health; totally unsuccessful hardscape plazas; ugly streetscapes with naked bare walls, lack of street trees and landscaping, etc.

thank you!