In my last post, I began reviewing two of my favorite books from Witold Rybczynski, someone I consider one of the best authors in architecture and urban studies. The first post covered Last Harvest (2007) . Contrast that to City Life (1995), where Rybczynski theorizes:

“…the American city has been a stage for the ideas of ordinary people: the small business man on Main Street, the franchisee along the commercial strip, the family in the suburbs. It all adds up to a disparate vision of the city. Perhaps the American urban stage is best described as cinematic rather than theatrical. A jumbled back lot with cheek-by-jowl assortment of different sets for different productions….”

Like Last Harvest, there are many digressions along the way. In this case into:

- Etymology

- Overviews of works by Lynch, Mumford, Sitte, and others

- Design impacts of Burnham and Olmsted

- Paradigmatic urban forms

- Expansion of Fernand Braudel’s theory of stages in city development to include industrial, post-industrial, and information-age cities

- The Laws of the Indies

- De Tocqueville’s visit to the States

- The Land Ordinance of 1785

- Immigration

- Real estate speculation

- The Columbian Exposition and the Civic Art (City Beautiful) movement

The interesting contrasts Rybczynski describes between North American and European cities have a lot to do with the fact that the New World was basically (to the colonists) a blank slate. But there were important differences between Hispanic, French, and English colonial urbanization that resulted in patterns that last into the 21st century.

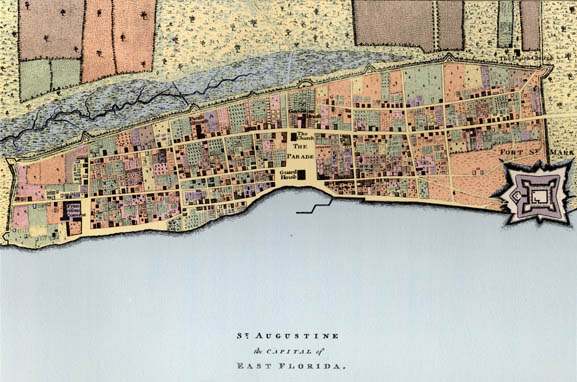

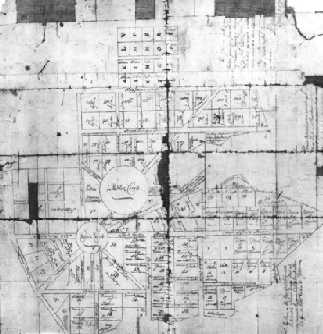

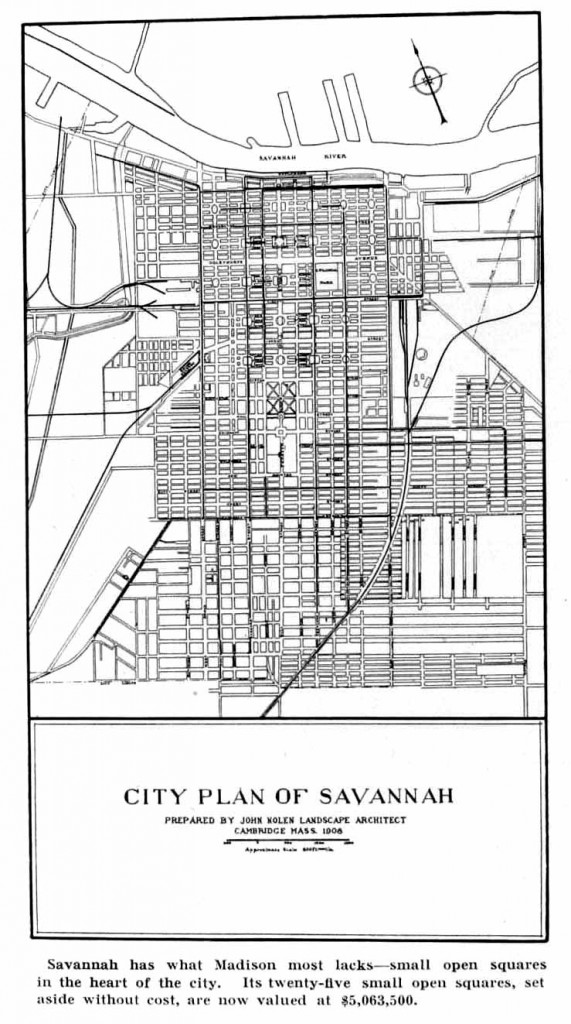

Wonderful brief histories and analysis are provided on cities as diverse as Saint Augustine, Quebec, Montreal, New Orleans, New York, Boston, New Haven, Charleston, Annapolis (a high-point in early planning thanks to our early governor, Francis Nicholson), Williamsburg, Philadelphia, Savannah, Woodstock, and Chicago. From these precedents, Rybczynski draws several generalities that distinguish North American cities dating back to their roots. Because land was cheap, “empty” and populations were sparse, people spread out. Open space was treasured, resulting in broad streets and public squares – the desire for spaciousness was built into our psyche in the infancy of our republic. Also, grids established an easy form of real estate development and the commodification of land. The imprint of religious tolerance and democratic governance can be found in the patterns of open spaces, relationships of civic and institutional buildings, and the focus on individual lots for houses.

A large impact on the form of our cities is, of course, functional zoning that separates uses and robs places of variety and vitality. Thus, a good many pages are devoted to early zoning ordinances (Los Angeles – 1907 and New York – 1916), building heights, and uses. In large part, as a reaction to the Civic Art ideals, the First National Conference on City Planning in 1909 deemed attempts to beautify cities “as exercises in ‘civic vanity’ and ‘external adornment.’ The bureaucrats and engineers felt that city planning should be concerned with engineering, economic efficiency, and social reform, not aesthetics. They asserted that whatever functioned well would automatically produce a beautiful, or at least acceptable, urban environment.” Sigh, we still suffer from the results of such thinking.

A large portion of the second half of the book details the tensions between competing theories, governmental policies, and the flight of the population to the suburbs. All of these intertwined ideas are told, of course, through a wandering history with anecdotes, observations, and citations from numerous practitioners, government acts, and examples. These ideas are fleshed out in more detail in Rybczynski’s latest book, Makeshift Metropolis.

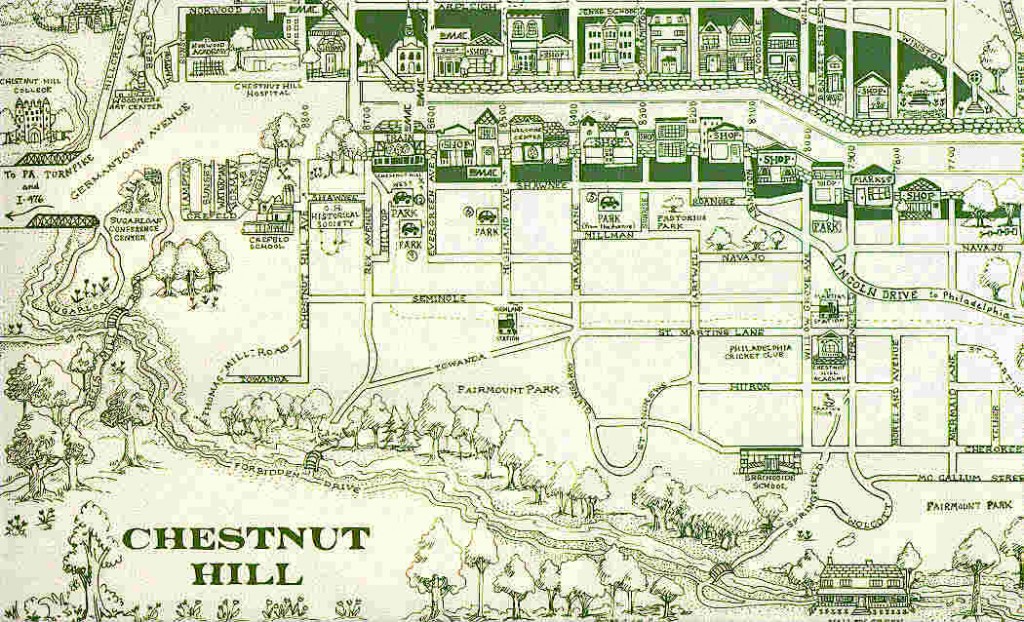

The final two chapters address the revitalization of downtowns and an approach Rybczynski calls “The Best of Both Worlds.” His paradigm is his home in Chestnut Hill in northwest Philadelphia. Chestnut Hill has several attributes:

- A diverse housing stock including multi-family, townhouse, and detached houses

- A population of about 10,000 people within less than 3 square miles (about 5 people per acre)

- A commercial main street

- Strong connections to Philadelphia’s cultural and business core and the greater metropolitan area

These attributes point to a networked system of mid-size centers within greater regions, but will require connections – electronic and physical – to each other with multi-modal transit, smart power grids, and numerous other more sustainable infrastructure upgrades that we need to begin planning for now.