Searching for Lost Cemeteries

Montgomery Planning maintains the Montgomery County Burial Sites Inventory, a listing of over 300 cemeteries and burial sites around the county dating from before the arrival of Europeans in Maryland to burial grounds still in use today. However, there are 80 burial sites in the inventory that are no longer visible, and historical records only tell us approximately where they were. This may be because the graves were never marked, or the markers have been moved or have deteriorated. We are looking for these lost burial grounds, and we hope to get some help from modern technology – ground penetrating radar (GPR) – to recover this part of the county’s hidden past.

M-NCPPC archaeology staff from Montgomery and Prince George’s counties practice using the GPR unit at the Griffith Family Cemetery in Montgomery County.

What is GPR?

A GPR unit transmits radio pulses downward and records the reflections of these waves as they go through the ground. Radio waves move through different materials at different speeds because of their physical or chemical properties. When a wave passes through a layer or an object that changes the speed of the wave, some of the energy will be reflected back to the surface and recorded. For example, if the radio waves move from average soil into an air pocket or some kinds of stone, they will speed up, sending one kind of reflection back to the unit. If they encounter material that slows them down, like a layer of wet soil, or blocks them altogether like metal, that will send a different kind of signal back to the unit.

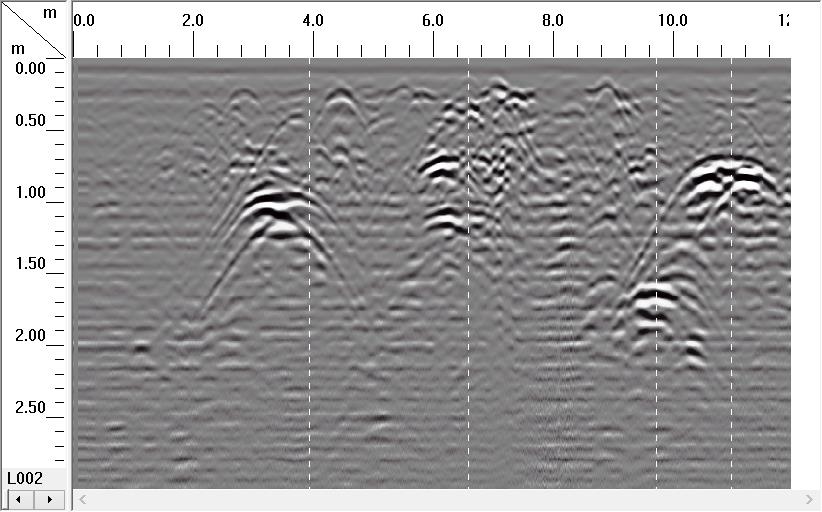

The technique was first patented in 1910, refined in the 1920s and used in 1929 to measure the depth of a glacier. GPR was used on archaeological sites by the 1970s. The picture below shows what these reflections look like on a computer screen and can indicate the location of features below ground that may be of interest to archaeologists. These include stone foundation walls, buried surfaces, metal objects, or air pockets, among other things. The anomalies (areas showing contrasting differences in how material transmits and reflects radio waves) can help find buried buildings, wells, or graves.

Taking a Test Drive

In June, Montgomery Planning, part of The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC), acquired a ground penetrating radar (GPR) unit for archaeological investigations. M-NCPPC archaeologists recently gathered at the Griffith Family Cemetery at the Edgehill Master Plan Historic Site in Montgomery County to practice data collection techniques. To collect data, archaeologists first lay out a grid of closely spaced parallel transects. A transect is a line along which the radar unit is pushed. The transects are spaced 25 centimeters (approximately 10 inches) apart to identify relatively small, buried objects. The instrument itself is about the size of a push lawnmower mounted on a three-wheel cart. For the technology to work, the antenna must be no more than an inch or two above the ground.

The photo below shows a profile of radar signals collected by the instrument as it moved along a transect from left to right. Up and down on the image is interpreted depth, and the parabolas, or curves, are anomalies. The anomalies in this case are probable grave-related features, the vertical dashed lines are the locations of grave markers we noted in the field as the instrument went past.

Profile view of grave anomalies in the Griffith Family Cemetery.

We used computer software to combine multiple transects so that you can see a composite plan view of anomalies recorded in the field in the photo below. This plan view is a little rough; we need to hone our technique so that our transects are more precisely aligned. Nevertheless, two rows of roughly rectangular anomalies are visible.

Composite plan view of grave anomalies (dark areas) in a portion of the Griffith Family Cemetery.

The real challenge comes in learning how to interpret the data. It is essential to understand how different materials that may be present affect radio waves. It may also be necessary to filter out background noise caused by TV broadcasts or cell phones. Features such as graves can sometimes be very subtle if there isn’t a vault, or if the coffin has deteriorated. Subtle anomalies may require a lot of careful data manipulation to make them visible. Acquiring the ability to distinguish common phenomena such as tree roots, animal burrows, and buried utility lines from features of interest to archaeologists requires a lot of patience and practice.

In August, four M-NCPPC archaeologists attended a two-day workshop specifically geared for archaeologists at the Nashua, NH headquarters of the manufacturer of our equipment, Geophysical Survey Systems, Inc. (GSSI). During the GSSI course, we learned how GPR data are generated and had the opportunity to practice processing GPR datasets to successfully interpret the scans.

Where We Hope to Investigate

GPR can help us understand many kinds of archaeological sites, but our priority will be to map incompletely marked cemeteries and look for lost burial grounds. Some of the sites of potential lost burial grounds are in heavily overgrown wooded areas that may make it impractical to use the GPR unit. If you couldn’t push a lawnmower across the area, you won’t be able to do a GPR survey either. We’ll start our efforts on relatively flat and open sites while we identify other more difficult locations and determine whether we can prepare them sufficiently to make a GPR survey realistic. As we collect our data, we will report back on what we learn.

M-NCPPC archaeologists Brian Crane (back left), Exa Grubb (back 2nd from left), Amelia Chisholm (2nd row, 2nd from left) and Jennifer Stabler (first row left) along with other students at the GSSI GPR Archaeology Workshop in Nashua, NH. Photo courtesy of GSSI, Inc.

About the author

Brian Crane is the archaeologist with Montgomery County Planning Department, part of The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC). He manages the Montgomery County Burial Sites Inventory program and provides input about archaeological sites during master planning and development review. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a Ph.D. in historical archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania. He joined the department’s Historic Preservation Program in September 2018.