The Montgomery County Historic Preservation Program is exploring the relationship between benevolent or mutual aid societies and Black schools, churches and cemeteries established over 100 years ago to better understand and preserve these important features of our past. These institutions were important to the growth of African American communities in Montgomery County. Many African American mutual aid societies were established after the Civil War to provide support for newly freed people who received no compensation for a lifetime of labor. This support often included financial assistance in the event of job loss or illness and burial after death. Benevolent society lodge halls were often located adjacent to or near African American schools, churches and burial grounds; these institutions were among the anchors for many early Black communities in Montgomery County.

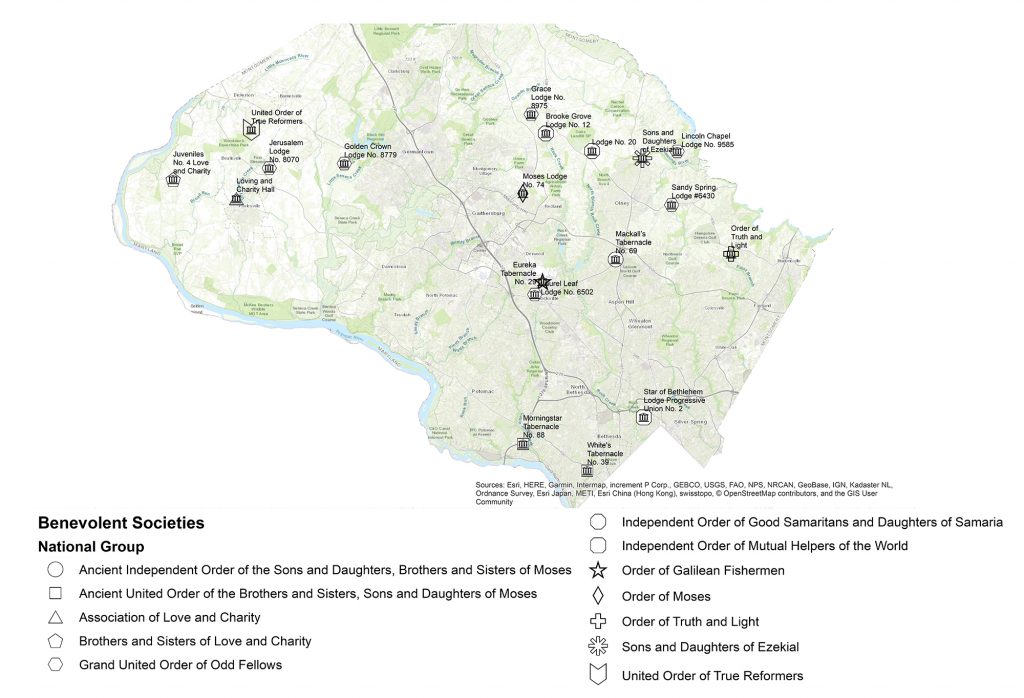

There are over 80 cemeteries in the Burial Sites Inventory that are associated with African American communities in one way or another. Most of these belong to churches, but there are also small family burial grounds and larger community cemeteries. Among the latter are cemeteries associated with benevolent societies, like the United Order of Galilean Fishermen in Rockville and Mackall’s Tabernacle in Norbeck. There were at least 19 local chapters of Black benevolent societies in Montgomery County.

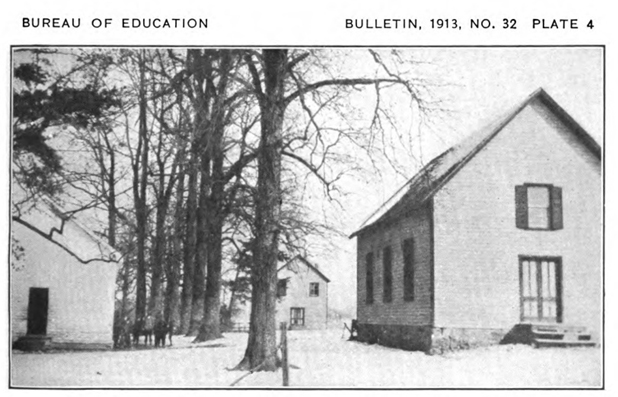

From left to right: Moses Hall School, Mackall Tabernacle Hall and Mount Pleasant Church in Norbeck, MD ca. 1912. The cemetery is behind and to the left of the hall.

Research into the location of these mutual aid society halls, African American churches, schools and cemeteries shows that they were often located close to each other. In the photograph above, you can see the cemetery, Moses Hall School, Mackall Tabernacle Hall and Mount Pleasant Church all immediately next to each other in Norbeck (the cemetery isn’t visible in the photo but is behind and to the left of the hall). This pattern can be found all over the county: in Martinsburg, Poolesville, Sellman/Big Woods, Norbeck, Bethesda and Gibson Grove among others.

Assembling a Picture From Fragments

The area around these institutions typically included residences and businesses owned by African Americans, such as the Hebron print shop on Wood Lane in Rockville, which was next to Jerusalem Mt. Pleasant United Methodist Church, down the street from Laurel Leaf Lodge 6502 of the Odd Fellows, and around the corner from the elementary school for Black children. Understanding these relationships can help us assemble a picture of communities from long ago when we only have fragmentary pieces: sometimes if you know a community had a lodge and school, but don’t know where they were, the location of other institutions like the church or cemetery might provide clues on where to find them.

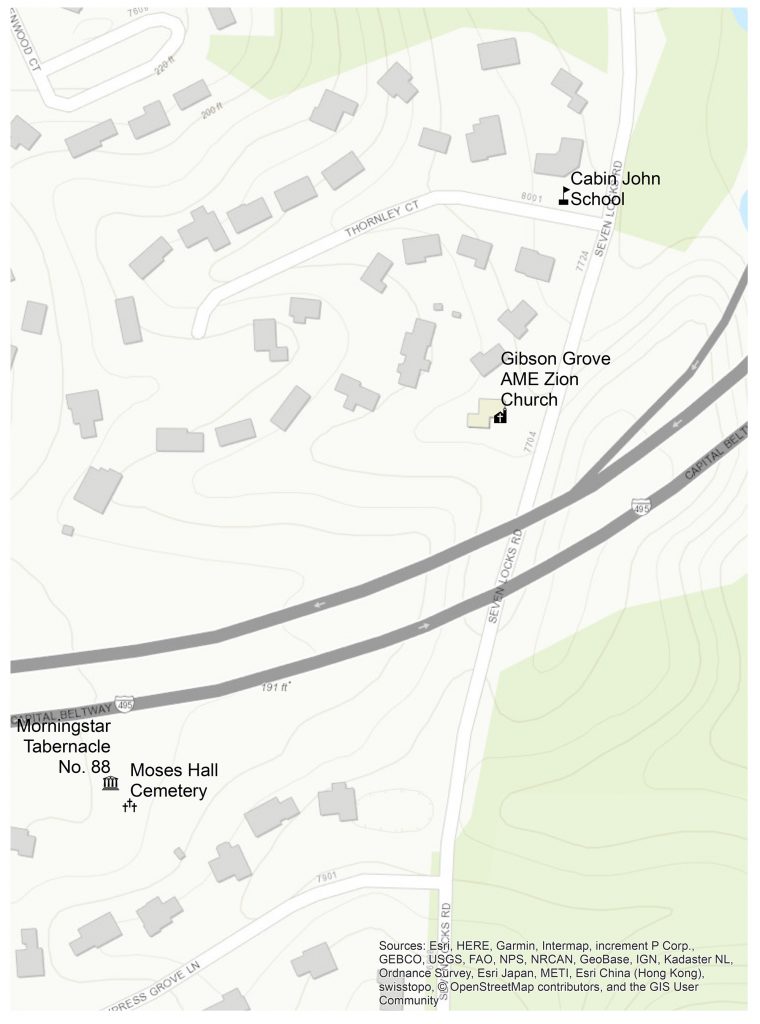

The Black communities in Norbeck, Emory Grove, Bethesda and Gibson Grove each included Moses Hall associated mutual aid societies. There were two chapters of The Ancient United Order of the Sons and Daughters, Brothers and Sisters of Moses in Montgomery County: White’s Tabernacle No. 39 (originally located in Tenleytown and which moved its cemetery to Bethesda) and Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 in Gibson Grove near Cabin John. There was also the Mackall Tabernacle of the Ancient Independent Order of Brothers and Sisters, Sons and Daughters of Moses in Norbeck, and Lodge No. 74 of the Independent Order of Moses in Emory Grove. At least three of these, Mackall’s Tabernacle, White’s Tabernacle No. 39 and Morningside Tabernacle No. 88 maintained cemeteries for their members. Morningside Tabernacle and Cemetery, Gibson Grove Church, the hall for Morningside Tabernacle No. 88 and the Cabin John School were all close to each other at the heart of the Gibson Grove community along Seven Locks Road.

Valuing Descendent Voices Today

Approximate locations of African American community institutions in the Gibson Grove community along Seven Locks Road.

Many historic places are vulnerable to loss from development, but this is especially true for African American sites that have not always been equitably valued in planning decisions. Highway construction plans in the 1950s and 60s were often sited through Black communities, such as when construction of the Beltway went straight through Gibson Grove, destroying part of the community and separating the church from the Moses Hall and cemetery. The hall burned down later in the same decade, but the cemetery is still present.

Today Montgomery Planning is working with descendants of people buried at Morningside Tabernacle No. 88 cemetery and concerned citizens in Cabin John to help make sure the community’s concerns about the potential effects of the I-495 and I-270 Managed Lanes Study to the remaining historical pieces of Gibson Grove are heard. Understanding how these institutional community building blocks related to each other helps us better understand the historical landscapes of which they were a part, and how best to protect and interpret these valuable but fragile pieces of our past.

Special thanks to L. Paige Whitely for providing assistance on some of the historical research.