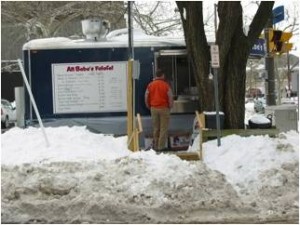

Elrafal serves falafel, gyro, and his mother’s recipe for ful medames, a traditional Egyptian street food of stewed fava beans that is so good, it will make you rethink your relationship to legumes. The guy is really cooking. His falafel is spiced with whole cardamom seeds and accompanied by distinctly seasoned red cabbage, banana peppers, and vinegary lettuce. It’s wrapped in a thinner pita than the gyros, which get a puffier pita bread. Elrafal takes pride in his product.

In the warm weather, he hangs a parakeet cage and he had built a little wooden deck where customers could stand at the truck’s window, but the County came around, told him he needed a permit, and that it would cost $2500. For a guy who sells beans, from a panel truck. The day we visited, Elrafal apologized for making us stand on a crumbling patch of asphalt and the rubber mats covering his power line. So good job there, a non-existent problem not solved.

The Clayboys shave ice stand in downtown Bethesda, a summer landmark that sets up outside the fountain at Barnes and Noble (watch John Styer sling syrup here), ran into some permit issues a few summers ago, but since the ices are well-loved by Bethesda children, this bit of civic disorder was given permit dispensation.

And I’m almost afraid to mention Jennifer’s Antojito truck that occasionally parks on River Road. Kids sneak out the back of Whitman to buy tacos and burritos. Why doesn’t he just park out in front of the school? Probably because his first market is the Hispanic workers paving the neighborhood with granite countertop, but also because—imagine the neighborhood outcry.

But other communities have recognized that food carts can add economic and social vitality. Los Angeles is setting up a mobile food court and the City of Portland just released this study as a baseline measurement of land use and other issues. The report is well-summarized here, and sees a planning role in:

- identifying possible cart locations

- connecting cart operators with existing programs

- promoting innovative urban design elements that support food carts.

This last one is the most interesting. Know a dead corner that would benefit from a good hot dog? Let us know.

By the way, this is not a new idea, food carts have a creditable history in American cities and, dating to 1893, Haven Brothers in Providence, Rhode Island is the granddaddy of them all. As described online: “An aluminum pick up truck masquerading as a diner that serves the greasiest food imaginable to Providence’s wastoids, insomniacs and street walkers.” Aaah, city life.

Richard Layman

Interesting how you don’t mention the banning of food trucks in Prince George’s County, perhaps as an anti-Latino thing, as well as the fit and start experiments with improving the quality and range of offerings of food carts in DC.

claudia kousoulas

I didn’t know this was an issue in Prince George’s; I’m glad you brought forward. I think this is all part of renegotiating our relationship with the suburbs–people, food, appearance, and function.

TomPier

great post as usual!